(content warning: mentions of like every bad thing that can happen to someone)

According to the CDC, you’re about 20% more likely to die on any given day if you’re in a rural area. Put another way, life expectancy in cities is a few years higher than outside of them.

This gap has widened in the past twenty years, and particularly the past ten1. In 1999, the death rate was only 7% higher in rural areas, but cities have gotten steadily safer while rural areas improved more slowly or even declined. This is usually attributed to the opioid epidemic, and the CDC also calls out heart disease. Cardiovascular care has gotten better in cities, while risk factors like obesity have increased in the country.

However, you’re much more likely to be murdered in cities. Almost twice as likely, according to this FBI table, though the exact proportion is sensitive to exactly how you define your terms.

If you’ve watched Fate/Stay Night with English subtitles, you may, at this point, have an objection.

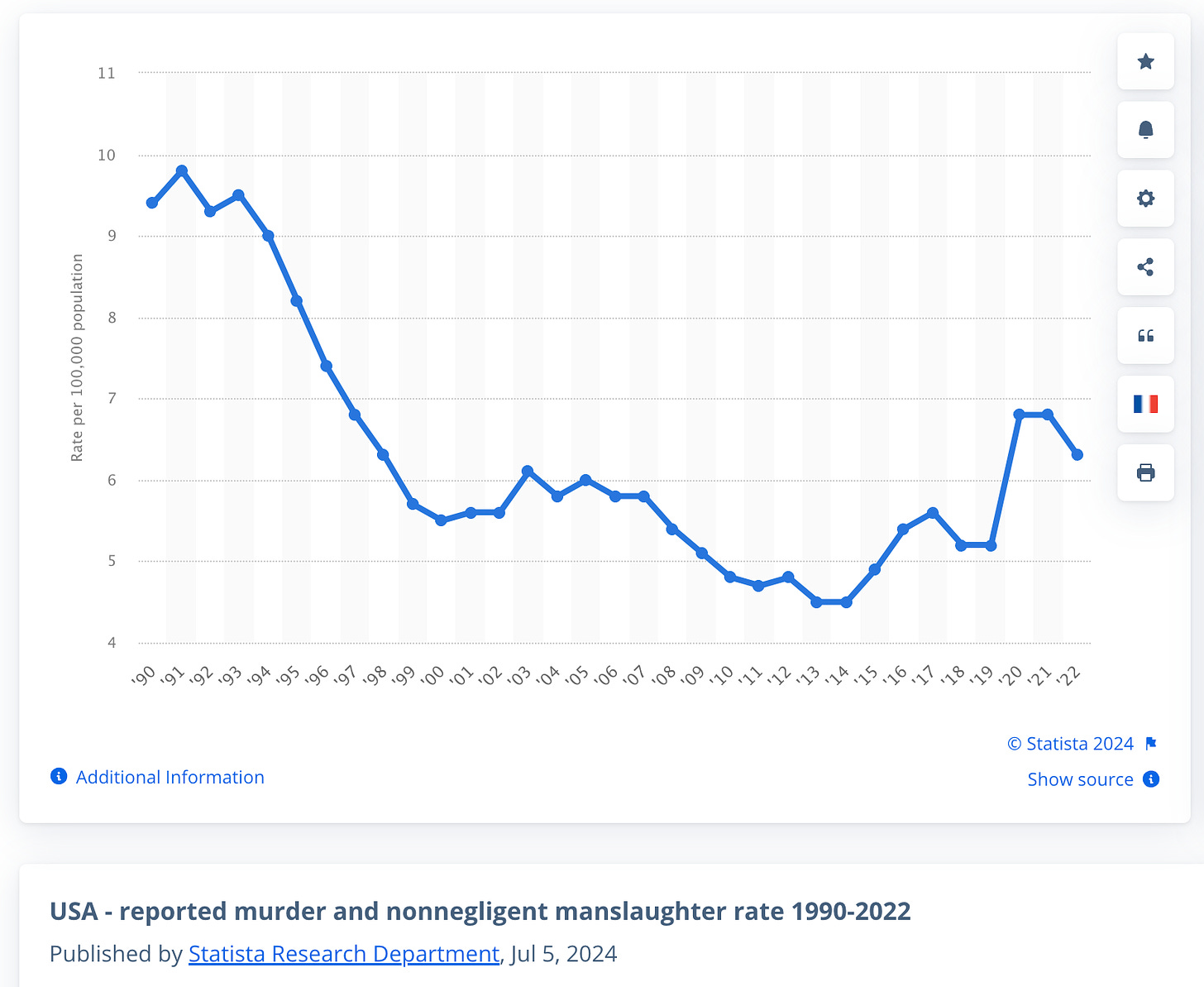

Shirou is correct as a matter of medicine. Homicide is fatal. The thing is, it’s also rare. Probably rarer than you think. About 20,000 people are murdered in the U.S. each year. For comparison, over 600,000 die of heart disease, 222,000 die of accidents, and 95,000 of diabetes. Suicides are more than twice as common as homicides.

These proportions mean that a 30% shift in the homicide rate has a similar impact to a 1% shift in the rate of fatal heart disease. You could hire all of the murderous cardiologists listed here and the net impact on your county’s life expectancy would be positive.

Injury and Trauma

Safety isn’t just about longer life, though. It’s also about not getting hurt, physically or mentally. Are urban areas still safer if we take this into account?

Yes.

When it comes to physical injuries, studies are pretty unanimous on this. A 2003 study in Colorado, for example, found that rural residents were 30% more likely to be seriously injured. A national NIH study had the same result. I can’t find anything saying anything radically different. Here, too, the huge ratio of accidental to intentional injury means that a slight difference in accident2 rate matters more than a large difference in assault rates.

Trauma is trickier to measure, because it’s more likely to go undiagnosed, probably in some areas more than others. Here’s a study finding equal amounts of PTSD in and out of cities. Here’s another with a similar finding for both PTSD and subclinical trauma. I’ll argue briefly that other statistics imply that PTSD is under-diagnosed in rural areas, meaning the actual rate is larger.

While being a victim of a violent crime, especially sexual assault, is more likely to result in trauma than a severe accident or illness, the ratio isn’t large enough to counteract the difference in frequency. From a table here, 49% of sexual assault victims eventually develop PTSD, while 16.8% of serious accident victims will, as will 10.4% of parents of severely ill children. From a table here, there were 63 million “preventable, medically consulted” unintentional injuries in 2022, versus (I’m going to round up) 500,000 sexual assaults. Putting those together, that means that out of 100,000 people, 150 will be sexually assaulted this year, 75 of whom will suffer PTSD as a result. 19,000 will suffer a serious accidental injury, and 3,000 will suffer PTSD from that. This suggests that the higher accident rate in rural areas is causing a lot of unreported trauma.

Etc.

My guess is the numbers come out the same way for loss of property (e.g. you’re more likely to crash your car in the suburbs than have it stolen in the city). But I’m getting into harder to quantify areas and also bumming myself out with all of these stats, so I’ll stop there, and move on to…

Policy Implications

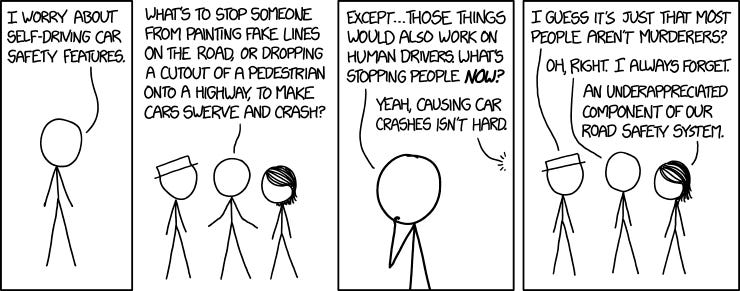

I don’t know if I really need to say this, but—deliberately increasing the crime rate will not make your county safer. The correlation between crime and safety reverses if you’re comparing similar-density areas. New York City, one of the lowest-crime cities in the country, had a life expectancy of 82.6 in 2019. Albuquerque, one of the highest, had a life expectancy about 6 years less.

In my opinion, the safety of cities is simply one case of the general principle that more people is more better. The more people you have around you, the more likely they are to give you an MRI, get you to a safe place if you pass out, or sprint up a flight of stairs and chase you down to return your wedding ring after it slipped off your finger without you noticing. Also, the more likely to punch you in the face for no reason, or try to shoot somebody near you from a motorcycle. (Strangers have done each of these things to me in NYC.) But—and this is important—help is much more common than harm.

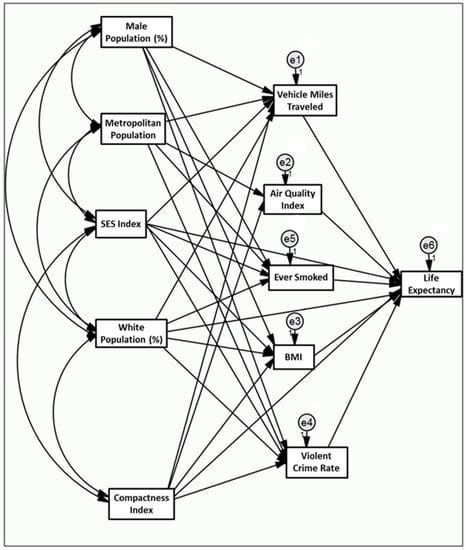

The key takeaway for policy is that increasing population density usually makes people safer, even though it usually also increases crime. It’s easier to measure at the national level, as in this study, but U.S.-based studies have shown that “compact” urban areas have a life expectancy more than two years longer than “sprawling” urban areas.

So, deregulate housing, deregulate immigration, support new parents better. Stop worrying so much about whether it’s the wrong sort of people moving into the new houses, immigrating, or reproducing.

I think. I’m not completely confident about that conclusion. It’s hard to tease apart cause and effect. Could be that population density and safety are both consequences of certain kinds of wealth, but not important drivers of it, creating a correlation without causation. I like this figure from the Hamidi et al. urban sprawl study, but it’s still just a theory.

What I Am Confident About

What all these stats unambiguously show is simpler. Crime is just not that important.

I get why no prominent politician has ever said that. I doubt any of them has said “leukemia is just not that important” either. The two do a comparable amount of damage, and it’s not negligible. Crime or leukemia can become the most important thing in the world when it affects you directly. It’s a cruel and alienating thing to say.

But it’s also kind of necessary to point out from time to time. Americans consistently rate crime as one of the most important issues for Congress to deal with. Politicians run on it as a core part of their platform. And we spend almost $300 billion a year on law enforcement and corrections.

Our government spends maybe $10 billion on all cancer research. Private companies and NGOs spend another $40 billion. Less than $300 million on leukemia in particular. Meaning that the ratio of anti-crime spending to anti-leukemia spending is about a thousand to one. Even though crime and leukemia kill the same number of people.3

If you want to empathize more with people who don’t think of crime as a big deal, imagine an impossible world where this was flipped. Leukemia deaths are headline news. Leukemia stats are a standard part of political discourse. We spend $300 billion a year fighting leukemia. Politicians run on an anti-leukemia platform.

And edgelords like me write obnoxious articles where we point out that leukemia is only 4% of all deaths from cancer, arguing that this hyperfocus on one particular kind of cancer is inefficient and misleading.

Crime gets the spotlight, I think, for two broad reasons. One of them is bias. We’ve got powerful instincts for avoiding dangerous people (and large cats). We never evolved instincts for avoiding cancer, because until very recently there wasn’t anything we could do about it. So we end up being obsessed with crime (and cats), and just try to put cancer out of our minds, until we can’t. “If it bleeds, it leads,” say media moguls, but that’s not quite true—leukemia, a.k.a. blood cancer, only makes headlines if someone famous gets it. Only certain kinds of fear responses get you views.

The other is more legit: law enforcement is a closer fit for many people’s idea of the role of government. We’re leery of private police forces, but slightly less leery of public police forces that are nominally accountable to the people they’re policing. It’s not obvious that it’s the government’s job to fund cancer research, or even cancer screening and treatment. Difficulty getting grants isn’t as much of a sign of a failed state as a high crime rate is.

But, pragmatically, it looks like our overall priorities as a society are skewed. We’re spending $300 billion on public law enforcement and $50 billion on all cancer research, public and private. If you add in the costs of treatment, it gets closer to even. Even though cancer is about thirty times as dangerous, and doesn’t try to think of counters to the moves you make. That mismatch means we’re more likely to be missing low-hanging fruit in medicine, while crime prevention is hitting diminishing returns.

Direct crime prevention, anyway. The primary driver of crime is poverty. If we do more to fight poverty, crime will continue to fall, as it’s fallen under every recent administration except Trump’s. And, more importantly, other things will get better too.

Bonus: Murder Skeptics Skepticism About Murder Statistics

There’s reason to be suspicious that the murder rate is actually higher than it appears.

The murder numbers I’ve been referencing in this article are mostly derived from either coroner’s reports or police records.4 That means that if you successfully make your killing look like an accident, suicide, or natural causes, you don’t show up in the stats. If they never find the body, it might show up as a missing persons case. Police in some jurisdictions have some bad incentives where they’d rather not have a murder on the books at all.

We really don’t know how often people get away with murder. About half of all murder cases are never solved, so it’s definitely most of the time, at least if you don’t count extrajudicial consequences like revenge killings. But how often are women poisoning their abusive husbands, with the coroner deciding not to look too hard for evidence of foul play? Those aren’t murder cases at all. The greatest detective in the world can only be in one place at a time (or zero, if they’re fictional), so murderers more competent than the best detective in town have a decent shot at outwitting the law.

If the murder rate is significantly higher than we think, how does that affect this article’s thesis? Since most causes of death are more common outside of cities, it’s likely the invisible murders are happening disproportionately there. That would mean that the difference in crime rates between urban and rural is smaller than it appears. So the more robust claim would be that the places that appear higher in crime are actually safer.

There’s another flavor of murder stat skepticism that comes from neoreactionaries, who generally argue that our culture is getting much worse as it gets more liberal, but that improvements in technology have masked the consequences. I’ve twice been linked to an article arguing that the only reason murder stats appear to have decreased with liberalism is that improvements in medical treatment mean that more people survive assaults. I don’t think the article deserves a link; it’s much less plausible and seems made up post hoc to justify their ideology.

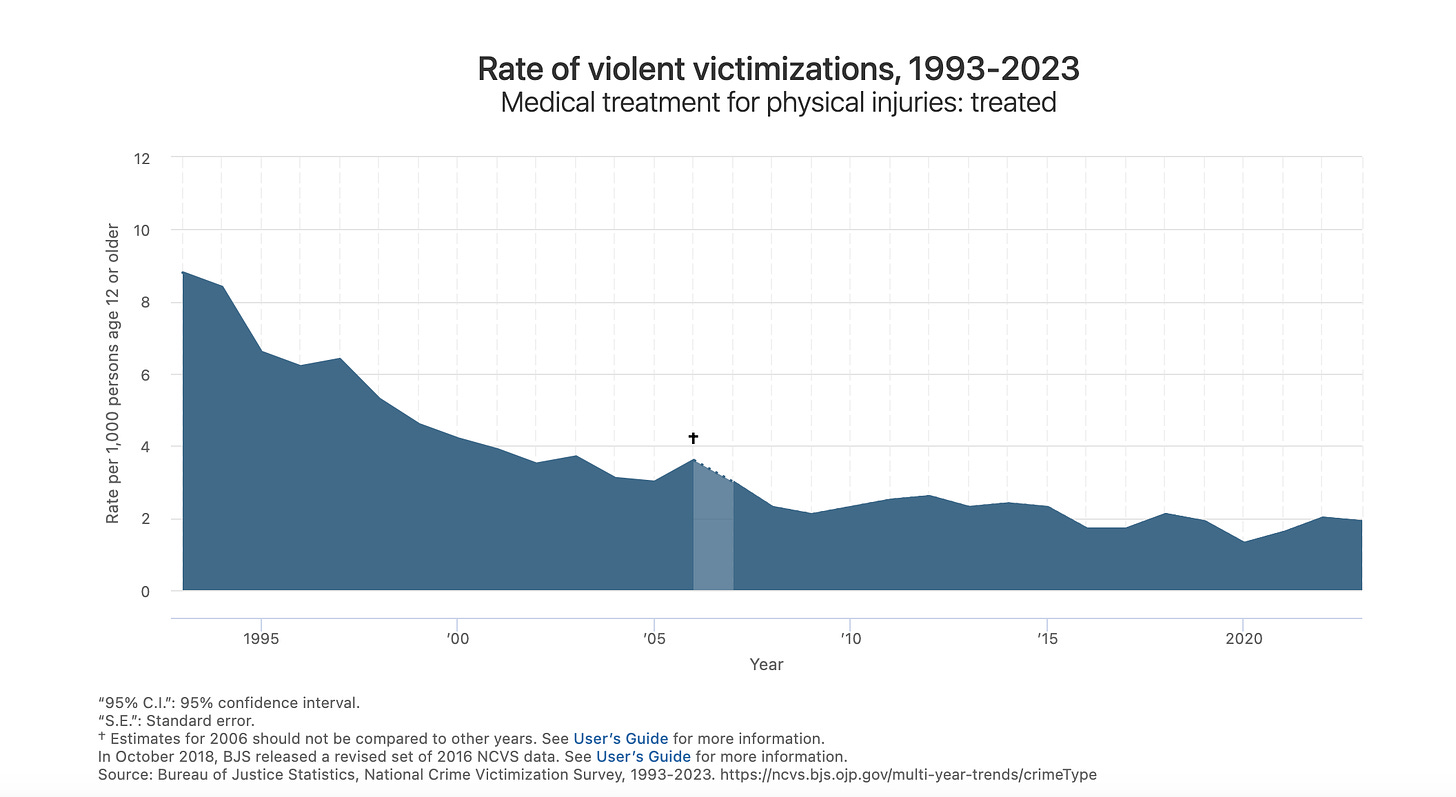

The big problem with this theory is that it predicts that the number of assaults should be increasing when the murder rate decreases. Instead, the two are tightly correlated.

To believe this theory, you need to assume that this correlation is a coincidence: a massive rise in near-lethal assaults was canceled out by a massive rise in police everywhere keeping them off the books to “juke their stats.” Annoying coincidences do sometimes happen in social science, but other than ideology there’s no reason to think it’s happening here. I’m not an expert, but it seems like aggravated assault would be the literal hardest stat to juke—you need the victims and hospitals to be in on the conspiracy. Also, not every precinct has an incentive to juke their stats. Now that states have noticed the Goodhart’s law problem, they’ve taken measures to fix it, and it seems likely stat-juking has gone down, because clearance rates have too.

Why isn’t medical treatment more noticeably increasing the ratio of aggravated assaults to murders? Sadly, I suspect the answer is that murderers are aware of improvements, and compensate. “Knife him in the gut and leave him for dead” was a better plan a hundred years ago than today, and if you’re killing someone on purpose, you probably know that.

COVID complicates things, but the CDC chunks by decade due to the census, so it doesn’t show up in the summary statistics used here.

“Accident,” in these stats, includes drug overdoses, which seems counterintuitive to me for some reason but I guess makes sense.

“But crime has second-order economic effects!” So does leukemia. “But it leaves victims and their families permanently scarred!” So does leukemia. “But leukemia doesn’t lower property values!” You can’t move away from leukemia. It follows you wherever you try to run. This is not a point in favor of leukemia.

In both cases, “murder” stands in for any intentional illegal killing. Different jurisdictions make different legal distinctions among murder, manslaughter, homicide, and probably some other terms.

I think another part of this is how human brains love a story with archetypes like good guys and bad guys. So we sort of fixate on these unknown "criminals" that are other and bad then we can reassure ourselves that we are good, everyone we know is good, etc. The reality is that every single person put in the right set of circumstances would commit a heinous crime. Also, crime is a social construct. So we don't want to stop and think of the environmental influences and get into the complexity so we stick to good guys/bad guys thinking.

Absolutely fascinating