The phrase “a house divided cannot stand” is almost always used to mean something like “united we stand, divided we fall.” Lincoln, in its most famous usage, did a neat lawyerly trick and transformed that into the logically equivalent “since we can assume we will not fall, we will definitely not remain divided”—the United States would either end up all slave states or all free states, because if it stayed half-and-half, it would soon cease to be a country. More commonly, “a house divided cannot stand” is used in rhetoric meant to stifle dissent—stop disagreeing with me; fall in line so we’re stronger against our external enemies.

The thing is, Jesus is the one who said “a house divided cannot stand,” and he wasn’t talking about the forces of righteousness. He was talking about Hell.

Y’all Need Midrash

There’s a story that shows up twice in the Gospels. Jesus is going around performing helpful miracles, and the dominant religious authorities, the Pharisees, feel threatened and skeptical. They accuse Jesus of using demonic power, and claiming that it’s holy.

Jesus points out that his miracles include exorcising (“casting out”) demons. The Pharisees counter that a higher-ranking demon can order a lower-ranking demon to stop possessing someone, so this doesn’t prove anything.

In Matthew, Jesus responds like so:

Every kingdom divided against itself is brought to desolation; and every city or house divided against itself shall not stand.

And if Satan cast out Satan, he is divided against himself; how shall then his kingdom stand?

In Mark, his line is very similar:

And if a kingdom be divided against itself, that kingdom cannot stand.

And if a house be divided against itself, that house cannot stand.

And if Satan rise up against himself, and be divided, he cannot stand, but hath an end.

In other words, Hell is strong. If demons were to start casting out other demons, Hell would be weak. Therefore, demons don’t cast out other demons.

This story has been taking up background computing cycles in my brain for years. It bugged me because it just seems like a really bad argument, from Jesus. Consider what the Pharisees are hypothesizing—Hell is trying to create a false messiah, whose religion will trick the entire world into following Satan while thinking they’re following God. With the potential gains that high, surely they could sacrifice a pawn or two?

Yet two different gospels found this worth recording. And these are Jews and Romans we’re talking about—possibly the world’s greatest experts at debate at the time. They must have been hearing something more persuasive in those words.

I can finally stop stewing over this, because I’ve thought of an alternate interpretation.

Alternate interpretation is a thing my people have been doing since long before Martin Luther. I was raised in a Jewish culture much more Jesus-like than Pharisee-like, thanks to pluralism born of diaspora. One of the ways Jews like to engage with holy texts is called midrash. Midrash is the precise opposite of dogmatic Catholicism. It treats all well-reasoned interpretations as valid, even ones that contradict each other, or sound like they’re trolling. The Torah is a perfect work, right? The direct word of a perfect author. Therefore, it can’t have any unintended interpretations, as those would be flaws. Also, Jews believe that when the author gave us the Torah, He was implicitly forfeiting his authority over it. So even when a voice booms out from the Heavens and tells you you’re reading it wrong, you’re allowed to invoke the Death of the Author. This exact thing happens in the Talmud, the second-to-most-sacred text in most Judaisms.

(The title of this section is a play on the “Y’all Need Jesus” meme, which itself is kind of a midrash, in that it comes from a misquotation of a Kanye lyric and nobody minds. And there’s definitely a rabbi somewhere who would read this and say “that’s not what midrash is!” But she’s not the boss of me.)

The Gospels are criminally under-midrashed. Lemme explain what Jesus was actually saying.

It’s easy to read the bits about houses and kingdoms as meaning that Jesus is speaking generally, about all organizations, not just Hell. But we know from the rest of the Gospels that he’s not speaking about his own organization. Look at the people he picks for his first disciples and apostles. Judas, who betrays him. Thomas, who doubts him. Peter, who denies him. Those weren’t mistakes. They were part of a successful plan.

Jesus makes two prophecies about Peter. One, that Peter is the rock on which Jesus will build an immortal church. Two, that on the night Jesus dies, Peter will disavow him three times. Both come true. As early Christianity got more and more authoritarian, Peter’s disavowal became uniformly interpreted as a sin, a moment of human weakness. But Jesus never calls it a sin. Jesus told his disciples, in Matthew:

Behold, I send you forth as sheep in the midst of wolves: be ye therefore wise as serpents, and harmless as doves.

Be careful, Jesus says, until it comes time to speak truth to power. Then be reckless.

“Doubting Thomas” also gets a bad rap. When Thomas hears people claiming that Jesus has been resurrected, he tells people that he won’t believe it until he gets some empirical evidence—he doesn’t want to just see someone who looks like Jesus, he wants to check if the wounds match and personally test if he can go incorporeal. After eight days of this, Jesus appears to him, in front of witnesses, and allows him to check. Thomas doubts no more. Again, people describe this as a failing on Thomas’s part. Maybe. Jesus did like faith. But it was certainly part of the plan. Having someone going around being skeptical, describing well-designed empirical tests they’d like to conduct, and then being persuaded? That’s a great way to get more believers! Why else would Jesus have picked Thomas? Why else wait for eight days before shutting him down? Thomas’s doubt made the movement stronger, not weaker.

I’m not going to try to rehabilitate Judas, although I hear there’s a pretty popular musical in that area. But we know his betrayal was foreseen and depended on.

A possible counter-argument starts “but maybe Jesus was just working with what was available. Maybe he could only find nine good disciples, but needed twelve, so he brought in three defective ones to round it out.” This we can refute by reference to Genesis 18—if there are only nine righteous men in a city, it will be destroyed in fire. Ten is the minimum. As the area was not subjected to the same fate as Sodom before Jesus arrived, we can reliably conclude that there were at least ten good disciples available.

What Kind of House Falls Apart When Divided?

Jesus was not calling for unity. He was very explicit on this point. Let Caesar try for absolute authority, not you. When people get violently disagreeable, just flee to another city. So what was he saying about Hell?

Hell, Jesus asserts, would fall if demons started casting out other demons. So would the Roman Empire, if it allowed too much division. But as we’ve seen, Jesus’s own church would and does not fall from division.

Hell would fall from even the appearance of disunity. Even if demons were ordering lower-ranking demons to depart, in strict accordance with the hierarchy and as part of a master plan to corrupt the world, their whole organization would soon collapse. We can infer from this that Hell depends on a perception of total unity. If demons were seen to be in apparent conflict, the legions of Hell would at once rebel (they did it once before, after all). The only reason they stay in line is that they don’t think there’s any other option. Hell is utterly dependent on authoritarianism. That dependency is a weakness. Jesus is believed, because people are allowed to doubt him. The Devil must always be assumed to be lying, because nobody would be allowed to call him out on it.

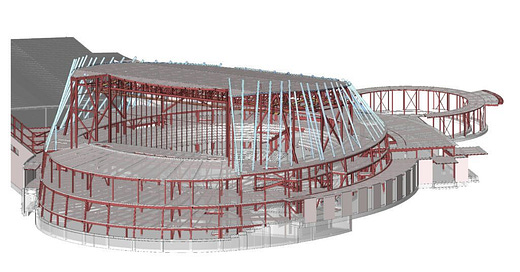

When Jesus talks about houses, kingdoms, and Hell, he’s talking about tyranny. These aren’t do’s, they’re don’ts. A robust, resilient structure is one with division. This is true on the literal, architectural level, as a carpenter presumably knew. It’s also true on the symbolic level. Everything worthy thrives on dissent.

In Conclusion

What’s my ultimate point here? What exactly am I encouraging you to believe Jesus was saying? I don’t think I can say it better than by sharing what is from beginning to end the most powerful five-minute sermon I’ve ever seen. Delivered by an atheist, in Las Vegas.

Bonus: Rock Puns

When Jesus calls Peter “the rock on which I will build my church,” he’s making a pun. In Greek, the language the Gospels came to us in, the word for rock is petra. What would Jesus do? First and foremost, make puns.

This Greek word also plays into my all-time favorite story of a radical reinterpretation of a Biblical text, involving the creation of the rock citadel known as Petra. Why I think of it as a radical reinterpretation of a Biblical text will need to wait for a full post, but the fun fact here is that Petra was built and run by Bedouins, not Greeks, so this is probably not the original name. The best guess for the original name sounds a lot like the English word “rock”.

I very much enjoy this youtube channel's tiny doses of Talmud, I never knew some of the wild stories in there. She has a very humorous take. https://www.youtube.com/@MiriamAnzovin