Berkson's Paradox Is Everywhere

An introduction to a useful concept, and a worked example of using a concept.

In the 1940s, statisticians in hospitals were making a deadly mistake. One such doctor/statistician, whose undergrad degree had been in physics, published a paper (reprinted here) explaining where they were going wrong. In his conclusion, he takes pains to point out that the mistake has nothing to do with medicine. “The same results as shown here,” Joseph Berkson writes, “would appear if the sampling were applied to randomly distributed cards instead of patients.”

He was quite correct. His results are applicable to almost every facet of human experience.

Ending Up In The Hospital (the original example)

Suppose you have a hunch that having an inflamed gallbladder made you more at risk for diabetes, or made diabetes worse. You decide to test this by studying patients at the hospital you work at. So you do a controlled study—are patients with one condition more likely to have the other than a randomly selected group of other patients? You use whatever statistical method is the current standard (you’d get the same result with today’s methods as 1946’s). You’re likely to find something really surprising! Having an inflamed gallbladder makes the subjects slightly less likely to have diabetes. Weird.

In reality, inflamed gallbladders do increase the risk of diabetes. The problem is that all of your subjects were patients in a hospital. If you’re in the hospital, you definitely have a medical condition. So if you don’t have an inflamed gallbladder, you always have something else, while if you do have one, you sometimes have something else. So within the hospital population, having an inflamed gallbladder makes all other conditions less likely.

Counting Cards (the suggested generalization)

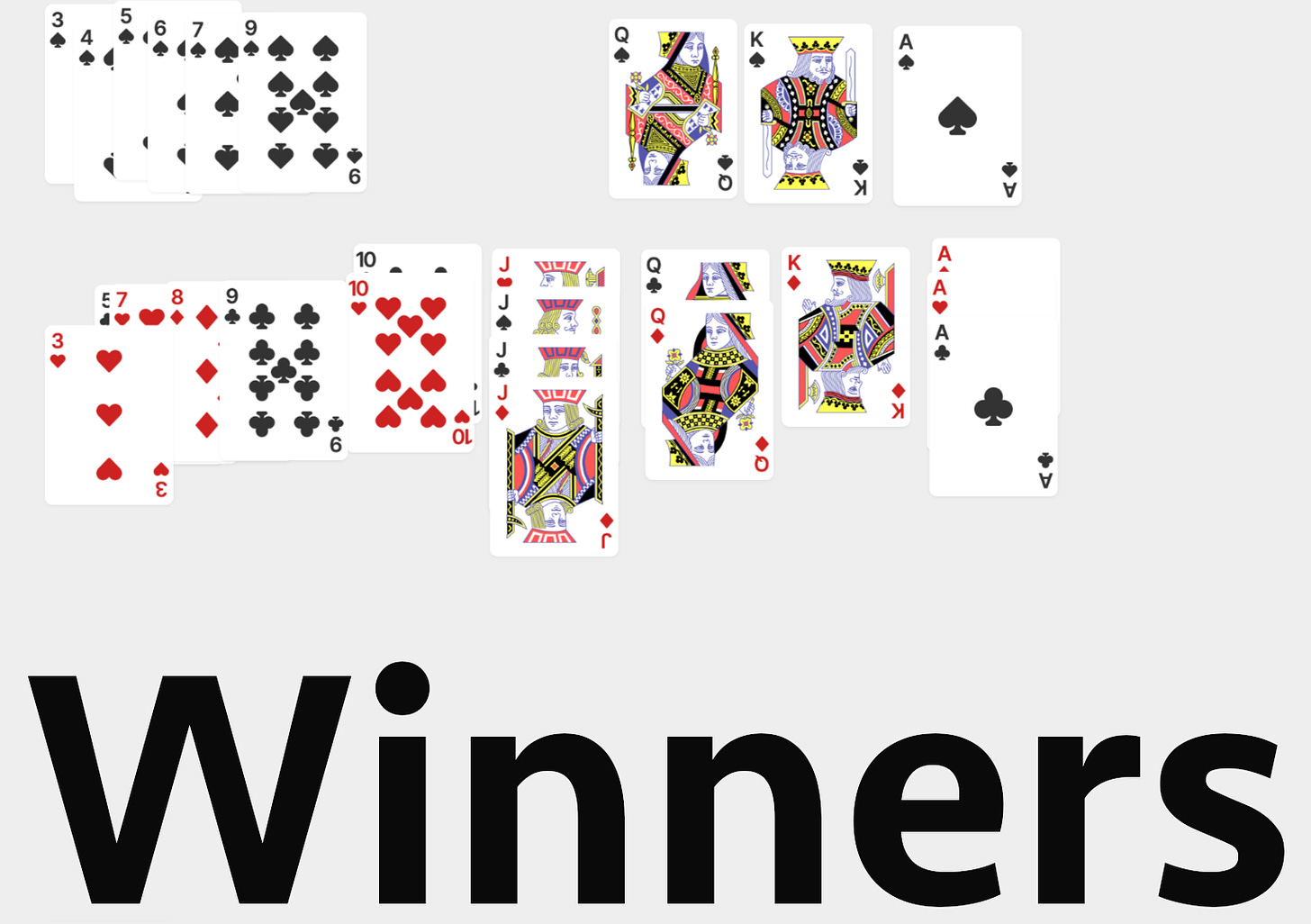

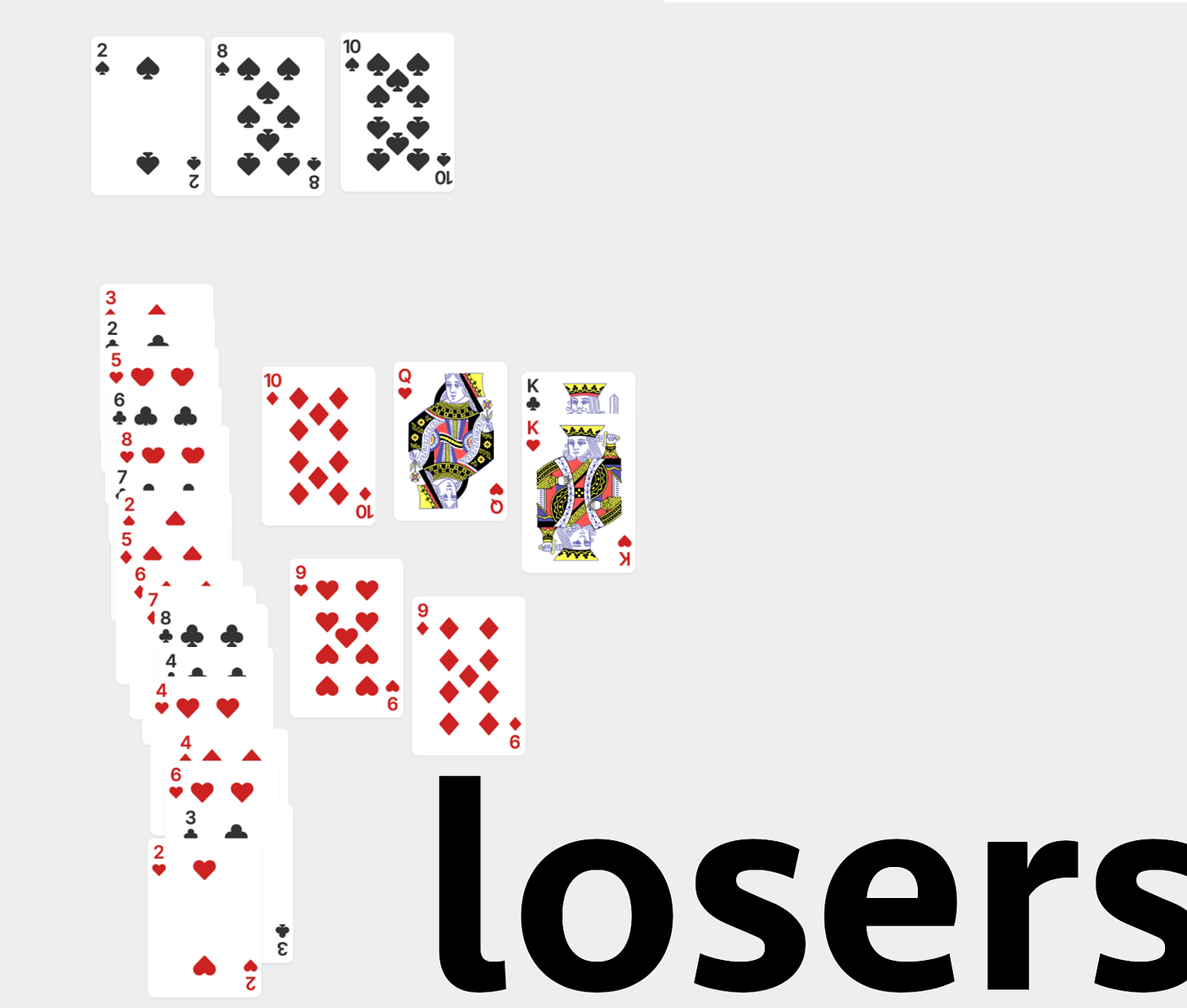

Berkson mentions the idea of applying the same principle to cards, but leaves it as an exercise for the reader. I think it’s a useful one. Say we play a simple game with a regular deck of playing cards: we flip over two cards, and whichever one “wins” goes in a winner’s pile, and the other one goes in a loser’s pile (in a tie, pick randomly). A card wins if its value is higher, except that spades always beat non-spades. We repeat this process 26 times, so that we end up evenly dividing the deck into two piles.

Now, if we look in the winner’s pile, we’ll mostly see high cards. Every so often, a 3 can sneak in by beating a 2, but that’s much rarer than a 10 getting in. But we’ll also see plenty of low spades, because even the lowly 2 of spades beats the anything of anything else. So, in that pile, the average spade will have a lower value than the average heart.

But we know that the suits all have the same set of values—their average in the entire deck is the same. So we might be thinking “oh, I bet the relationship is reversed in the loser’s pile, so that it averages out.” Wrong! If we look in the loser’s pile, we’ll see mostly low cards of all suits, including the rare spade that got beaten by a higher spade. But we’ll see a few high cards too—ones that got beaten by spades. We’ll see few or zero high spades, because it’s really hard for a high spade to lose. So all of the high cards will be from other suits. So here, also, spades are lower-value on average.

We’ve tested at this point literally all of the cards in the deck. And somehow we’ve still come to the wrong conclusion when applied to the deck as a whole. (The deeply unfair fact that this can ever happen is called Simpson’s Paradox).

From Medicine to Grand Theory of Everything In Two Easy Steps

By suggesting we think about replacing patients with cards, Berkson has sent us on a quest. What is the most abstract possible way we can phrase his insight? How many of the details can we cut out and have the result remain?

Do we need the “exactly two piles” aspect? Patient/non-patient is a binary, so both examples so far have been. But, no. If we were doing the same study in the ICU, the rest of the hospital, and a random non-hospitalized group, we still might see the effect in all three groups. If each medical condition correlates with severity of illness, then anything that’s tiered by severity of illness will show a negative correlation inside that tier.

We don’t need numbers, we don’t need a domain, and we also don’t need the general reality to be anything specific—this issue can exaggerate a real relationship, cancel out a weak one in the other direction, or create one out of thin air. And one final thing we can drop is the value judgment. Berkson’s Paradox doesn’t mean you get the wrong answer, depending on what you’re trying to do. Inflamed gallbladders in a patient really do mean that the patient is less likely to have diabetes—if the restricted population is all you care about, the effect is real.

So here’s the effect in the most abstract form I can get it to: If there’s a subcategory of stuff that you’re interested in, and membership in that subcategory can be driven by multiple causes, those causes will be more negatively correlated in the subcategory than in the category as a whole.

Now we can go nuts.

Too Many Examples

Acting: Your tier of success as an actor is driven by looks, ability, and luck. So whether we’re watching a hit movie or a community theater production, the less conventionally attractive people will, on average, be the better actors.

Branding: Some wine critics will tell you that if you’re in a store picking out a bottle in a hurry, you should favor the worse-looking bottles. The store made a decision about which brands to stock, presumably based both on quality (the thing you care about) and how it’ll look on the shelf (which you probably don’t). Or it made the decision based on sales, which were probably driven by those too.

Competencies: Another classic illustration of Berkson’s is studies done on college campuses to measure various academic abilities. They inevitably find that students who are better at test-taking are worse at turning in their homework on time. The students with higher SAT scores tend to spend less time studying. And so on. Colleges are each tiered on overall academic competence, so the individual components are negatively correlated. Or you can get in based on your athletic ability, leading to something we all know but forget how deeply weird it is: college students who are better athletes are worse at academics.

Dignity: Suppose you meet two people with the same social status, or the same job title, whom you know nothing about. One has a quiet dignity about them, while the other is wearing bunny ears. The second one is probably more talented. This is one of the quickest ways in TV to communicate to an audience that someone is a genius—show them doing their job in an unusually undignified way.

Elasticity: There’s two reasons not to change something—either it ain’t broke, or it’d be too much of a pain to fix it. Or some combination of the two. So anything that’s difficult to change is more likely to be broken.

Farming Subsidies: Food is good. Without farms, we’d all die. So there are many government programs and policies designed to make life easier for farmers. A 2021 U.N. study found that these policies actually make the food situation worse, on net. The U.S. sends its farmers billions of dollars, by various means, and the result is to significantly lower the quality and quantity of the food they produce. Why? The main reason, per the report, is that most of the subsidies are targeted. In a subsidy-less world, farmers grow the crops they can make the most profit off of, which means the ones for which there’s the most demand and that can be grown and harvested the most efficiently. Demand is correlated with quality, and efficiency is correlated with quantity (and, the study notes, lower carbon footprint). When you add in a subsidy for growing corn, you create another factor in farmers’ decision-making, which partially crowds out the other ones. No subsidies would probably lead to better outcomes, and untargeted subsidies might be even better than that. Economists have actually been saying this for a while, but see “Elasticity” above. Not only is eliminating a targeted subsidy going to make you very unpopular with a specific group, the shock to the system could be net harmful in the short term.

Genetics: Suppose a gene has a noticeable negative effect, like the ones that cause sickle-cell anemia, but is common in some populations anyway. If it’s been around for a while, why hasn’t it been selected against? The answer is usually that it has multiple effects, which add up to being positive (or at least increasing your average number of healthy children) on net. In the case of sickle-cell anemia, two copies of the gene make you sick, but one copy makes you more resistant to malaria. So areas that have high amounts of malaria also have higher incidence of sickle-cell anemia. It’s not the main reason that donating to the Malaria Consortium is currently considered one of the most helpful things you can do, but fighting malaria will also, in the long run, fight anemia.

Hard Problems: An old problem that’s complicated and niche is probably easier to solve than one that’s simple, once you understand it. If a problem is both easy to understand and easy to solve, why hasn’t it been solved yet?

Immunization Paranoia: Getting vaccinated against a deadly disease increases your likelihood of dying in a fire or getting struck by lightning. Because you’ll live longer, on average, so you’ll have more opportunities to go for walks in thunderstorms. Longevity is correlated with being vaccinated and with not getting struck by lightning, so if you look at any one age cohort, you’ll see a correlation.

Junk Bonds: If you’re lucky enough to be able to start contributing to a retirement account like a 401(k) while you’re still a long way off from retirement, you should make risky investments with your retirement savings at first, such as in “junk bonds,” bonds assessed as having a high chance of defaulting. That’s because the market price of an investment is determined by both its expected value and its risk level. So at a given price point, a riskier investment will pay out more on average (as long as it’s on the “efficient frontier”).

Karaoke: Plenty of singers report that they sing a little better when they’re a little buzzed. But I think we all know that someone singing while very slightly drunk is likely to be worse than someone sober. Why? Your willingness to sing in public is determined by two factors: your singing ability and your inability to feel shame. Alcohol is technically a depressant, but the first thing it depresses is often your inhibitions. Uninhibited people aren’t necessarily worse singers, but uninhibited people who are singing are worse on average.

Learning: I haven’t ranted about standardized education in a minute, so let me just sneak one in here. Subjects get added in to a curriculum based on two criteria—how much we’d like everybody to know them, and how easily can we teach and test it. This means that classes we’ve taken in things that are easy to teach and test are less useful, on average. If your English teacher taught you anything about how to write in an entertaining and accessible way, we know it’s because they thought that was important for you to learn, because that’s really hard to grade. If they taught you the difference between an adjective and an adverb, it might’ve been more because they could make and grade a multiple-choice test on it with next-to-zero effort, not because it made you write good.

Moral Arbitrage:

“Well I’ve been talking to my own guy,” said Maya. “And there are a ton of forbidden techniques. Some of them are pretty obvious spooky stories to tell around the campfire, but others seem like they might be legit. It’s hard to say, I guess, and March can give you the logs if you want, but what I’m looking for are things that they think are beyond the pale and which I don’t.”

“You’re doing … moral arbitrage?” asked Perry.

Maya gave him a very serious nod. “You think about the things that are important to them, then you think about the things that are important to us, and that’s your comparative advantage. You’re a disrupter, basically.”

“You really were in tech,” said Perry with a laugh. “Sound logic, it just makes me uncomfortable.”

“And obviously if there are forbidden techniques that we want to use, we need to keep it from them,” said Maya. “Stuff that they’d think is beyond the pale, but that we think is a nothingburger. I don’t know what that would be, exactly, but we’re already heavily disconnected from their culture, right? We’ll brainstorm some sins.”

—Thresholder, by Alexander Wales (currently being published as a free web series)

Notoriety: People become cultural heroes when they’re some combination of highly effective and highly altruistic. So a historical person known for something negative was probably more successful than a hero known for something positive. The four most common historical rulers to be featured in movies are Napoleon, Hitler, Lincoln, and Churchill. Lincoln and Churchill get in because they helped win one important war in which they were on the right side of history. Napoleon and Hitler get into the list because they conquered continental Europe and caused millions of deaths.

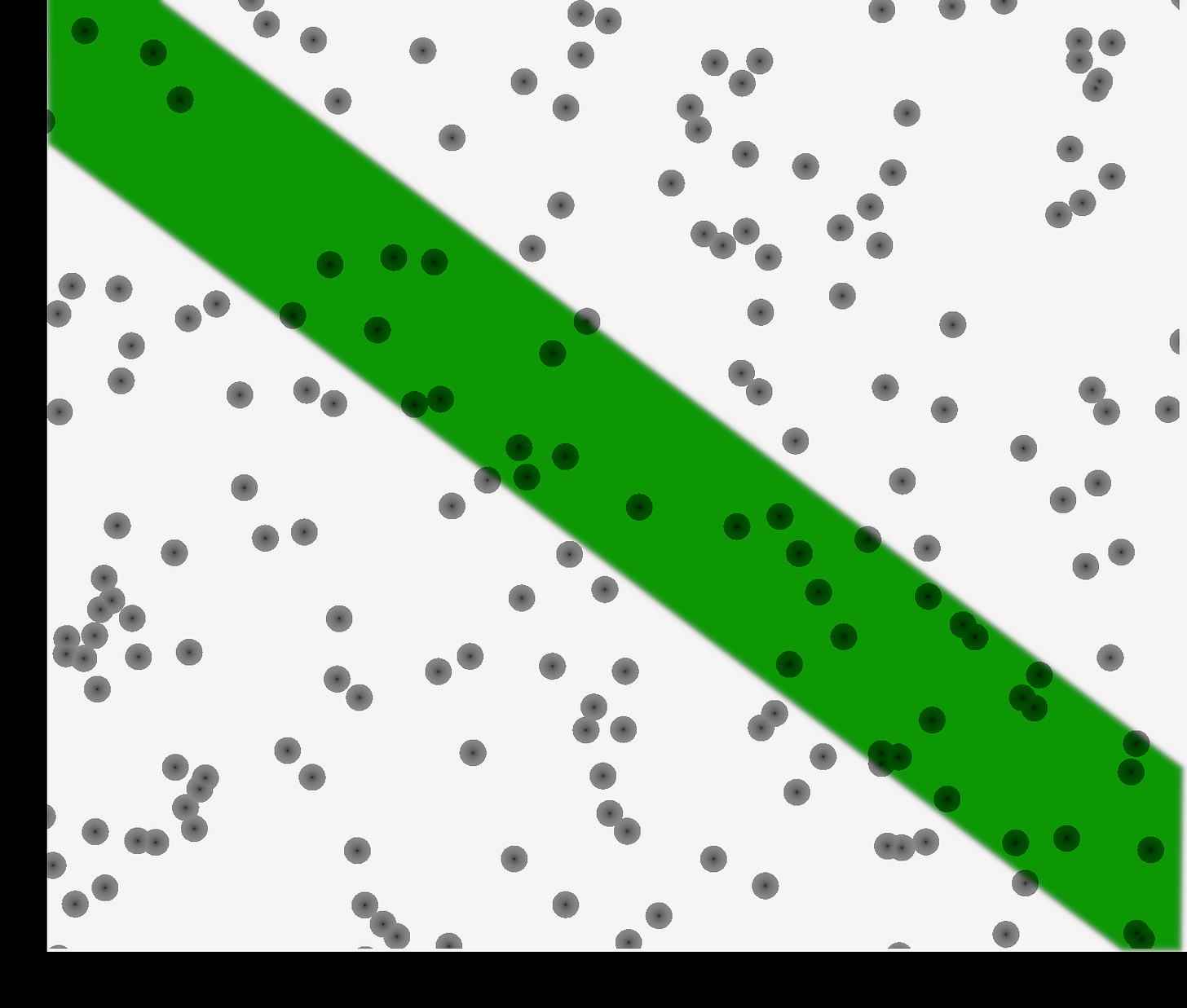

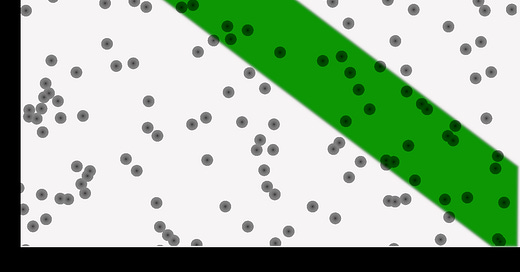

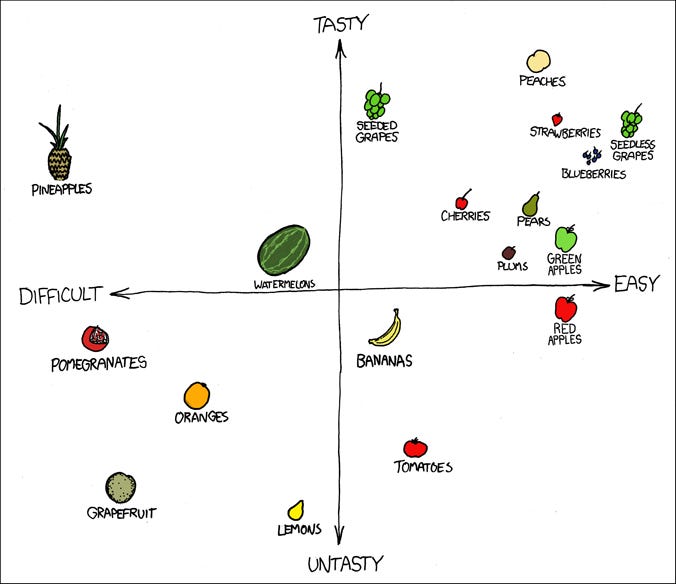

Oranges: See this graphic from XKCD:

Setting things like price aside, we generally eat fruit that’s some combination of easy to eat, tasty, and high in Vitamin C. Ergo, fruit that’s high in Vitamin C is either difficult to eat, like pineapples, or so sour there’s a song about it being impossible to eat, like lemons, or both, like grapefruit. Oranges were probably created deliberately, and definitely spread all over the world, because they were both high in C and closer to the middle of this graph. Note also that “easy to eat” and “tasty” are positively correlated. This is because there’s a strong enough relationship between those two variables to overwhelm the Berkson effect going the other way. Fruit that has either quality has evolved, and/or been bred, to encourage animals to eat it, a process that encourages both ease and deliciousness.

I have no explanation for pomegranates.

Policy: There are trillions of possible policies, only a tiny fraction of which ever get actually proposed. Nobody’s ever proposed putting all the world’s grapefruit on a rocket and aiming it at the HD 167425 star system. That would be a bad idea, and it’s obviously bad. The proposals we actually end up talking about are either good, or seem good. The proposals we end up hotly debating are either good-but-seem-bad, or bad-but-seem-good. A proposal that is a good idea, and can’t be easily reframed to sound like a bad idea, will just quietly get consensus. So the policies we spend the most time talking about show a negative correlation between how good they sound and how good they are.

Quibbling: There’s a phenomenon, also known as “bikeshedding,” wherein a committee ends up spending more time talking about the proposed color to paint the bike shed than the proposed architecture of a new building. There’s two reasons to pick out a specific part of a proposal to criticize. It has to seem wrong to you, and you have to feel like you might know better than the proposer. The more comfortable you feel talking about something, the lower the threshold for wrongness it needs. If you’re not an architect, the blueprints would have to look pretty wonky before you spoke up about them. But almost anybody can have an opinion about teal vs. turquoise, so even if the color of the shed is the least important detail to you, you might bring it up anyway.

Relationship Material: “Why are all the good ones _____” is a cliché joke format for a reason. If somebody is widely considered a catch, but still isn’t married by your age, there’s probably something else that people have considered disqualifying, or that makes them uninterested in marriage.

Survivorship Bias: Wikipedia has a great article about this. It’s the special case of the paradox where the reason you’re looking at a restricted sample is that the rest of the sample is gone, so all the things that correlate with survival look negatively correlated with each other.

Technical vs. Conceptual Complexity: From Terence Tao. If something is conceptually complex, it takes a lot of writing to get it across. If it’s technically complex, it also takes a lot of writing to get it across. If it’s neither, you can state it in a few lines. If it’s both, you should probably write a different paper. So, on average, as measured by word count in a published technical paper, the part that’s more technical is about simpler things.

User-Friendliness: In my experience, enterprise software, the applications written to be used by everyone in an organization, tends to be less easy to use than apps meant for personal use, even though enterprise is often the bigger moneymaker, and user-friendliness would be just as desirable. If you’re using an app, it’s either because you want to or because you’ve been ordered to. So the kind of app you’re ordered to use tends to be the kind of app you don’t want to use.

Vainglory: If you’ve heard that someone is a really great pool player, and then you meet them and they start bragging about how good they are at pool, your guess at how good they are probably goes down. There’s not necessarily any relationship between modesty and skill. But being so skilled that people talk about you is one way to get a reputation for skill, and another way is by talking yourself up. So a modest person with a reputation for skill probably deserves that reputation more, on average.

Wait Times: If you see people lined up around a downtown city block for food from one place, that place is probably pretty good and probably pretty cheap. People choose where to eat based on quality, convenience, and price, so if a restaurant or food cart is inconvenient, but still popular, it’s probably some combination of great food and great prices. If it’s inconvenient and expensive, the food’s probably even better.

X-Ray Analysis: Machine-learning-based approaches to diagnosing people from things like X-rays have a lot of promise. But they also have a unique pitfall—the neural network can spot correlations that aren’t actually useful, and start using them without anybody realizing. This Science article gives an example: x-rays taken while lying down look different from x-rays taken while standing up, and if you weren’t able to stand up for your x-ray, it’s more likely that you’re seriously ill. So you can end up with an expensive, cutting-edge model that just detects whether the patient is currently bedridden or not. Berkson’s paradox can generate a whole slew of traps like this—if you train a model on inpatient x-rays only, it’ll also “learn” that all serious diseases are negatively correlated with each other.

Yelling: Raising your voice when talking to someone carries the connotation that you think they’re not paying you enough respect. We pay attention to someone when we respect them or when they speak loudly, so if someone is speaking loudly, they don’t get no respect.

Zoology: We are literally creatures of Berkson’s Paradox. Plato observed this in his Protagoras dialog, giving a mythological explanation:

Epimetheus said to Prometheus: "Let me distribute, and do you

inspect." This was agreed, and Epimetheus made the distribution.

There were some to whom he gave strength without swiftness,

while he equipped the weaker with swiftness; some he armed, and

others he left unarmed; and devised for the latter some other means

of preservation, making some large, and having their size as a protection,

and others small, whose nature was to fly in the air or burrow

in the ground; this was to be their way of escape. Thus did he

compensate them with the view of preventing any race from

becoming extinct.…

Thus did Epimetheus, who, not being very wise, forgot that he had distributed among the brute animals all the qualities which he had to give-and when he came to man, who was still unprovided, he was terribly perplexed. Now while he was in this perplexity, Prometheus came to inspect the distribution, and he found that the other animals were suitably furnished, but that man alone was naked and shoeless, and had neither bed nor arms of defence.

There have been species that were as defenseless as us, but less intelligent. The dodo, for example.

This Is Why We Math

Ideas are easiest to understand when you provide lots of concrete details. But they’re at their most powerful when you take the details away. This is, to a first approximation, the point of mathematics. If you talk about numbers as vaguely as possible, you end up being able to prove theorems that apply both to numbers and to other things, like functions or sets of numbers. You end up with results where you have no idea what, if anything, you’re talking about in the real world, and then decades later some rocket scientist is like “oh, if we think of orbital trajectories as points in an n-dimensional manifold, this all gets a lot easier!”

The meta-application of Berkson’s Paradox is left as an exercise for the reader.

Important Cautionary Note

There is, possibly, a tendency to get overly enthusiastic with grand theories of everything, especially among people with some kind of mathematical background. As soon as physicists get tenure, they’re free to rip off their mask and explain that actually, they’ve always felt that probably all unsolved problems in other disciplines can be solved with the math they already know. Reality is always, always, always more complicated than the model.

Berkson may have gone through this lifecycle within his own discipline. Only ten years later, in a paper he wrote for the Mayo Clinic and summarized in a letter to Congress, he argued that there was probably no causal relationship between smoking and lung cancer. It’s just an illusion, he said, caused by selection bias. Easy to say in hindsight, but it sure reads like he was over-applying his own method.

Grand theories of everything are best understood as ways of coming up with ideas, not truths. They point you toward hypotheses, or ways of thinking, that might not otherwise have occurred to you. They are not, in themselves, something that gives you special insight. They’re strategies that, if you’re lucky, might help you guess what it’d be helpful to learn.

this piece reminds me of this book that i'm currently reading:

Statistics As Principled Argument, by Robert P. Abelson https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/226575.Statistics_As_Principled_Argument

I LOLed at "No Respect." I had heard the wine label advice, but didn't realize it was part of such a huge —if limited— way of thinking. Anyway, this was a great one!