Human Timelines Should Be Log Scale

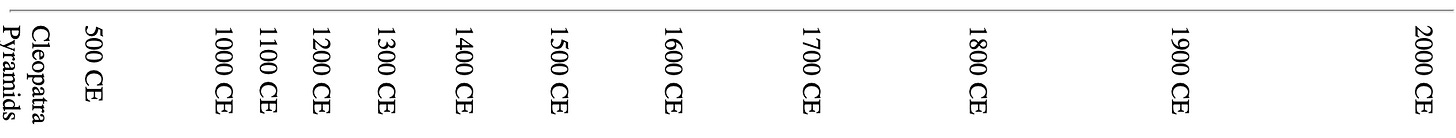

Did you know? The year 1600 happened closer to the year 1000 than to the year 2000.

How do you measure a year? If you’re concerned with the physical revolution of the Earth around the sun, say because you care about seasons, you can define it as exactly that: one revolution per year. If you’re concerned with daily cycles, measure it in 365-ish daylights, sunsets, or midnights. But what about if you’re concerned with humans? What if you measured it in cups of coffee? Laughter? Strife? How about love?

The ratio of (human) laughter to (Earth) sunsets has grown approximately exponentially for the past ten thousand years. Any universal human experience gets more common with population growth, which has been exponential, or faster, over almost every time period. So when you draw a timeline of any part of human history, it should be scaled to reflect that. Between this sunset and the next, eight billion solar days worth of experiences and activity will occur. Back when there were only a million humans on Earth, it’d take 22 years for humanity to live as much as we’ll do tomorrow.

One of those mind-boggling facts people love to break out is that Cleopatra was born closer to the present day than to the building of the Great Pyramid. We intuitively disbelieve this. To some extent this is just a reflection of how unusually old and culturally continuous Egypt is. But also, if we’re thinking on a human scale, that intuition is actually correct. In between the Pyramids and Cleopatra, far fewer humans were around to reshape the world than in between Cleopatra and the present day. That means more history, more buildings, more science, more art. There’s a greater distance almost any way you measure it. We just usually happen to measure it in seasonal cycles, one of the few human-relevant things that happened more times in the first period than the second.

Person-years are a weird and awkward way to measure time if you’re trying to be precise about it. The Black Death slowed down time, so that the second half of the 14th century was shorter than the first half. The Baby Boom sped time up. That just sounds like a headache.

But if you’re just trying to make a timeline that nudges our intuition to the right place, modeling population growth as an exponential curve works well enough. Roughly the same amount of change happened in each inch of the line.

I’d even suggest plotting time on a log scale when it’s the x-axis in a line chart. Kurzweil did this to argue that the technological singularity was near, but it’s also just a useful way to get your whole line visible on the same graph, rather than hugging the x-axis for most of history and then screaming upward at the end.

We should probably start leveling up our flexibility with marking time now, before space travel puts large populations in different relativistic reference frames. At that point, if we’re not prepared, we’ll hit a Y2K bug in our own brains, when single-dimensional time stops making sense altogether.

Bonus: Earworm Removal

I’m sorry for the earworm encoded into the first paragraph of this post. But, you know, it’s been inevitably playing in my head whether I referenced it or not, and misery loves company.

Fortunately, there are solutions! Songs that loop endlessly in your head usually do so because of a lack of resolution—either you can’t remember how they end, or they don’t end in a musical resolution. So sometimes the cure is to just listen to the song from beginning to end. If that doesn’t work, or isn’t feasible, you can displace it with a shorter tune that does resolve. “Happy Birthday” is a popular choice—ends definitively and many brains refuse to loop it on aesthetic grounds. Even shorter are some advertising jingles—the ones for brands that advertise themselves as products you can rely upon and forget about. My go-to is We Are Farmers (bum buh dum bum bum bum bum).