Inconvenience Is A Bad Way To Measure Security

The cognitive bias that enables vote suppression and security theater.

Security is hard to think about concretely. I mean “security” in the general sense here that includes election security, computer security, airline security, and any other field where you are designing something ahead of time that an intelligent enemy will try to break or subvert. That “intelligent enemy” is why it’s difficult to think about; intelligent enemies do weird things, things that an orderly approach will overlook.

A classic example of failed security design is a door that’s tougher than the wall around it. It can make sense to make a door tough so that an intruder would have trouble breaking it down. It can feel like the tougher you make it, the better. But as soon as you make it stronger than the wall, you’re wasting time and resources. You’re no longer making things any more difficult for the intruder by further reinforcing the door, because now if they’re breaking anything down, they’re breaking down the wall instead.

These kinds of errors are everywhere, and I often enjoy spotting them. One of my favorites, that I see over and over again, is the “ID required only for people who the guard recognizes” de facto rule. Have you ever worked in a building where people had to have a custom-made photo ID on them at all times? It makes some sense, right? If you just gave out slips of paper or something, those could be easily forged or stolen, but a photo ID lets you prove that you belong there. It’s a minor annoyance, so people don’t always comply at first, but you address that by having security guards challenge anyone without their ID showing and expel them if they don’t have it. That’s the idea. But of course, there are always visitors, and new people who haven’t had time to get their ID yet. So in all but the most secure locations, there’s a “temporary ID” system — if someone vouches for you, you get one of those easily forged or stolen slips of paper to show the guards instead. So what’s the actual system here? If a guard sees someone they recognize without their ID, that person is breaking the rules and must be expelled. But if they see someone they don’t recognize with a slip of paper of the appropriate color, they leave them alone. So why would an intruder ever bother with a photo id? They just need to somehow get a temporary badge. The permanent IDs are not actually adding any difficulty for an intruder, and therefore have no security value. But they persist, because they feel like they do. And the main reason they feel like they do is that mild inconvenience of getting one and carrying it around.

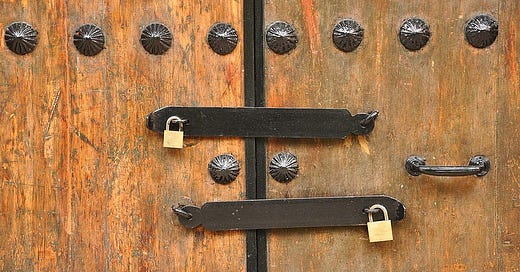

Without realizing it, we use a measure’s inconvenience to legitimate users as a proxy for its security value — it’s easier to think about inconvenience than security, and the two often go together, so it’s a useful cognitive shortcut. If I can just wander into a room by accident, I can assume it’s not a secure room, without having to think concretely about its setup. If to get into a different room I have to unlock a door first, that inconvenience to me is a strong sign that it’s a more secure place to leave my backpack. The lock would prevent an intruder from simply getting into the room the obvious way, and it’s a signal that someone put in effort to secure the room.

This kind of shortcut, using something easier to measure as a proxy for something correlated, is fine if you’re careful about its limitations. If you’re not, it can lead you astray — you’ll sometimes see people putting five different locks on their door. Two locks might be better than one, if they’re different kinds of locks. But there are basically no intruders who will pick four locks but be stymied by a fifth. People add that fifth lock because it inconveniences them, to have to open it every time, just as much as the fourth lock did — the inconvenience of successive locks is additive, so it feels incorrectly like the security value must also be additive. There’s no diminishing inconvenience with each new lock, but there are sharply diminishing returns, so the correlation breaks. The proxy misleads.

This fallacy, equating inconvenience with security, leads to a lot of accidental damage — gratuitous inconvenience, insecure systems. But I feel moved to talk about it now, in October of 2020, because it can also be purposefully exploited by an intelligent enemy. What if you were co-designing a system with someone who secretly wanted it to be unusable, or barely usable? Your treacherous partner could put obstacle after obstacle in the path of legitimate use, and just claim that it was in the interest of security. They could sabotage your project without even really having to be sneaky, just acting in bad faith. This is what election security is like.

U.S. politics is structured such that there will almost always be two opposing sides, both with some influence on how voting is conducted, one of whom has, on average, wealthier voters. This means there will always be people with an incentive to increase the cost of voting, since it will deter their opponent’s voters more than theirs. Until a constitutional amendment banning it in 1964, this was often done directly, simply charging a fee (a “poll tax”). But increasing the inconvenience of voting has the equivalent effect — wealthier people are more likely to have the time, energy, and other resources to overcome them, and wealthier communities will tend to have more support. This trick is everywhere today, and politicians get away with it, brazenly, by falsely claiming to be making the election more secure.

Generally speaking, the politicians with the incentive to do this today are the Republicans. Nationally, in 2016, people from a household making less than $30,000 a year were more than twice as likely to describe themselves as Democrats than Republicans. The less scrupulous among them are acting on this incentive. If this demographic pattern is inverted in your area, the reverse might be the case, but this year the bulk of it seems to be Republicans exploiting the pandemic. The most obvious example of fake security, real inconvenience was defunding the postal service to prevent mail-in voting, as Trump said he was doing in August (and yes, I know it’s perilously subjective to claim that he said something). A hypothetical adversary taking advantage of the pandemic to submit massive amounts of fraudulent ballots would likely bypass the postal service entirely, or otherwise easily work around pockets of slow delivery. They’re not going to be mailing out envelopes one by one. Only legitimate voters (and other people who need mail) will be inconvenienced here.

A more typical approach has been to demand government-issued photo ID, which indeed would’ve been useful to prevent in-person voter fraud back when it was otherwise viable. But I at least don’t see a viable way someone would exploit the lack of it today at scale — if they’ve compromised the voter rolls, they’ll have a much easier time voting absentee. The true effect here is to deny the vote to the 7% of Americans who have otherwise no need for an ID and are unwilling or unable to take on the cost and inconvenience of getting one.

It can be tempting, when you see politicians arguing against inconveniences like this, to interpret it as part of a scheme to commit voter fraud. I can’t prove that’s not the case, and it has been in the past. But in making these judgments, I urge you to think concretely about the actual effects of election policies, and to remember that politicians rarely have the ability to compromise election security, but usually have an incentive to increase the cost of voting.

The broader takeaway I’d like you to have, beyond elections, is that inconvenience is an almost uniquely bad way to measure security. Equating the two not only gives cover to bad actors, but it leads to “security theater” — people given a security goal, with no idea how to achieve it, will create a bunch of inconvenience instead because it’s a visible sign that they’re trying. It’s a lot like how you can make people think your wine is better by making it more expensive — a negative is converted into a positive by consumers who don’t know any better. I unfortunately don’t have an equally easy cognitive shortcut to replace it with — security just truly is hard to think about. If and when you don’t have the time to think about it, I’d instead recommend paying attention to incentives instead. Trust an expert who’s staking their reputation on their advice, or copy the decisions someone’s making on their own behalf. Don’t trust a lock salesman about your need for more locks.