My first name is “Aaron.” I have mixed feelings about this. I’ve always appreciated being first in alphabetical order (and therefore hate aardvarks). But the biblical Aaron is terrible. (So is the Aaron in my civic religion, Aaron Burr, to whom the Hamilton musical is far kinder than he deserves).

Every biblical Aaron story is him making a mistake, and other people paying the price. He tells everyone to worship the Golden Calf, leading to divine fury and mass slaughter. He gives bad instructions to his sons for how to handle the Ark of the Covenant, a story which ends the same way Indiana Jones and the Raiders of the Lost Ark does. He demands excessive tithes, prompting a revolt from the charismatic leader Korah that it takes a miracle to defeat. He has the audacity after all this to say out loud that he wishes he had more authority, in punishment for which his sister Miriam is stricken with disease.

The burning bush told Moses to pick his brother Aaron as his spokesperson when dealing with Egypt. I think this was not because he’d be trustworthy, but because he’d be incompetent. Without Aaron actively making things worse, the pharaoh would have given in immediately after seeing Moses first demonstrate his power, and that wasn’t part of the divine plan. We needed the story. If Moses had been supposed to have a persuasive spokesperson, he’d have been told to go look up Korah.

Aaron escapes personal consequences…until his very last mistake. His people have been wandering in the desert for a long time. Miriam is dead. Water supplies, and morale, are running low. Fortunately, Moses and Aaron get a divine command. They are to assemble the people to witness, and then speak to a certain rock, asking it to bring forth water. It will, and then faith in their leadership will be restored (and also then they won’t die of thirst).

Moses doesn’t quite pull this off correctly.

And Moses and Aaron gathered the congregation together before the rock, and he said unto them, Hear now, ye rebels; must we fetch you water out of this rock?

And Moses lifted up his hand, and with his rod he smote the rock twice: and the water came out abundantly, and the congregation drank, and their beasts also.

Catch the problem? Nobody said he needed to strike the rock. He was supposed to use his words.

Ironically, after all this time having other people take the hit for his own mistakes, Aaron is now punished for Moses’s. Both of them are condemned to die in the desert. They don’t get to see the end of the journey, which happens soon after they die.

Some commentators say this is why the story specifies that Moses struck the stone twice. The first strike condemns Moses. The second condemns Aaron, for failing to stop him after he saw what he was doing.

The Sequel

Okay, fast forward a few thousand years. We’re no longer in the Bible, we’re in regular old history. According to local legend, the fateful striking of the stone took place in what is now southern Jordan, in a specific spot midway between the Dead Sea and the Gulf of Arabia. The Arabs passing through there would sometimes pay respect at places where they believed Moses, Aaron, and Miriam had been buried. It’s a reasonable inference, if you accept the historicity of Exodus at all. It’s a spot maximally far from all bodies of water, right near, but not quite in, the promised land.

The area didn’t have water…at least not in any useful form. There would occasionally be torrential floods, possibly creating temporary lakes, but nothing about the landscape was right to capture much of the water and create an oasis. So if a human or a beast came wandering into the area, even if it was right after a flood, there’d be no plants and very little to drink.

This was a shame! It’d be a great place for an oasis. Not only for people wandering in the desert, but for traders. It was on the Silk Road, the route that allowed China to export goods only they knew how to make (silk, duh, and china, also duh) to the Roman Empire, which they referred to as “the other China”.

The culture that passed through this spot the most often was the Nabateans, one of the groups meant when people say Bedouin. They were primarily nomadic, so they traveled the desert a lot. Not wandering, though. They knew where they were. They knew a lot about the desert, including what kind of landscape you need for an oasis to emerge. And they knew the story. The land was dry, but water could be drawn forth from the sandstone mountains, the story said. From a certain point of view, that’s what it said.

So they struck the stone. The project must been very slow going at first, because they couldn’t work in large groups, and couldn’t stay long, with the terrain so inhospitable. Maybe just every time they happened to pass through, they’d take a few whacks. Not at random, not hoping for a miracle. They had a design. Hit by hit, they carved an artificial oasis from the rock.

Once they could capture and purify water at all, there was probably a hard takeoff—more water meant more workers at a time, which meant more water. The singularity was nigh.

Now that they had a perfectly-located oasis, they had a new problem. Just as predators lurk near natural oases, knowing that prey will be forced to visit them eventually, bandits would lurk near this artificial one, knowing that traders carrying valuable goods would be forced to come by.

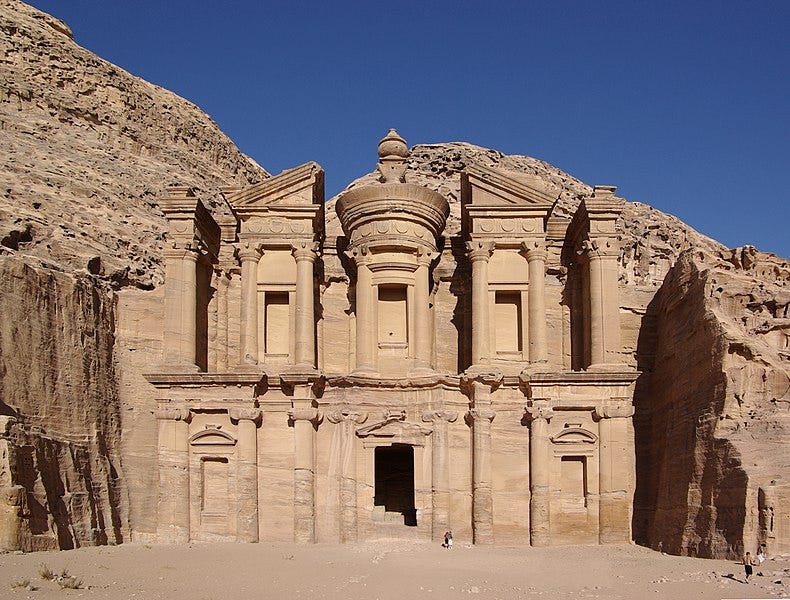

They solved this by carving the mountain into a castle.

This is so cool. I am finally okay with being named after Aaron, now that I’ve learned about his minor connection to this place.

The castle, built into a mountain in the middle of a desert, was invulnerable to attack. For centuries it protected the oasis, the Nabateans, the traders, the shrines to Aaron and his siblings, and (in a massive flex) at least one living tree.

Where you have riches and danger, you get castles. Where you have castles, you get kingdoms. One formed here. The Nabatean Kingdom, with this ridiculously cool place as its capital, minted coins with a horn of plenty on one side, and a king and queen on the other. Their government system seems to maybe have been that the first-born male child in each generation of the royal family became King and the first-born female child became Queen, and the two then ruled jointly. Fun little spin on the concept. They kept it up for a few centuries, then they decided the whole kingdom thing wasn’t working for them any more, turned the kingdom over to the Romans (somewhat voluntarily, by most accounts), and went back to being nomads.

The oldest name that we can confidently give to this place is Petra, Greek for rock. Greeks would have been traveling through the place often, and you can bet they talked about it to everyone they met. The Arabs in the area started calling it Al-Batra, presumably derived from the Greek name. It’s tricky, though, to figure out exactly how far back this name, and Petra itself, go…because there were rocks there, so there are plenty of ancient Greek texts that refer to a petra in the desert, and the distinction between common and proper nouns isn’t always apparent. If the Nabateans had their own name for it, at first, current thinking is that it was probably something like Raqmu, derived from a word not for rock itself, but for writing carved into rock. “Petra” was a discovery, a miracle, water for wanderers. “Raqmu” was an achievement, a technology, water for those who knew how to think long-term.

I am mostly writing about this because it’s cool and only a tiny bit to obliquely comment on current events. But there is one postscript to this story, one that might be vaguely inspiring.

Nabateans and Hannukah

Hannukah, once a minor Jewish holiday, has become one of its most central in places that have a winter. This is because it’s the Jewish Festival of Lights. Every culture that lives in a place with a winter has some kind of festival of lights in the middle of it, whether the lights are on Christmas trees or Chinese dragons. It’s an inherently important thing to do, regardless of what the festival supposedly signifies.

Which is good, because I kind of hate the thing Hannukah signifies. It’s a celebration of the victorious war of the Maccabean Jews against the Hellenic Jews, a war that by the end of it also was a war of independence against a larger empire. The Hellenic Jews sound, honestly, better to me as a culture, and that’s even after reading history written by the winners. And the Hellenic Jews probably would’ve been fine peacefully coexisting, it’s the other guys that started it. But maybe I’m just being contrary.

Anyway, Hamilton was right about one thing: if you want to win a war of independence against a larger empire, you need help from France, or the local equivalent. The Seleucid Empire, against whom the Maccabeans revolted, was in a cold war with the Nabateans. Accounts are fragmentary and confusing, but it seems like the Nabateans stepped in here, providing support and a hideout for the rebel army. Presumably for pragmatic reasons, but maybe they also felt a connection with them, having drawn water from the same rock.

Bonus: Hannukah as Distorted Reference to The Nabatean Petroleum Industry

The Nabateans straight-up had a petroleum industry. Petroleum, in those days, would just come bubbling up randomly in the Dead Sea. The Nabateans would camp out on the shore and watch for it. When one bubbled up near enough, they’d sail over in rafts and harvest it. The word petroleum comes from petra. It feels like a new word, but it’s quite old.

Petroleum wasn’t useful to them as fossil fuel, but as a way of making glue. They would render it into the sticky goo we call bitumen or asphalt (the other thing we call asphalt is gravel mixed with bitumen). The byproduct was a bunch of useless gasoline and lighter fluid. They, and their trading partners, used bitumen as an adhesive, often as a way of sealing a container. Also, the Egyptians bought it for their mummies.

All of that is true. What follows is a crackpot theory that, as far as I know, is unique to me, and which I do not actually believe. It’s fun, though.

Hannukah lasts for 8 days because of an ancient legend of unclear origin. When the Maccabees won, their first priority was to relight the eternal flame in the Holy Temple. The Seleucids had extinguished it, as part of their heavy-handed intervention that prompted the revolt. The problem was that the eternal flame, per the Torah, could only be lit using certified-pure olive oil, and almost all of the oil was in open containers and had to be assumed to have been desecrated. The process to make more pure oil only took a day…normally. But they’d all just finished winning a war, which means they were ritually unclean themselves. The process to ritually purify yourself after killing someone takes seven days. They couldn’t prepare pure oil while they still had blood on their hands.

One of the containers, though, was still sealed with the seal of the High Priest. It could safely be considered still-pure, and had enough oil to light the flame for a day. So they used it, and it miraculously lasted for eight days, just enough time for them to be able to replace it.

Now, as previously established, the Nabateans saved Hanukkah, militarily speaking. The Nabateans, whose most valuable export was a sealant, the preparation of which created highly flammable oil as a byproduct. So maybe, just maybe, this story is actually about the miraculous aid of the Nabateans, and it got a little garbled?

Your knowledge of things biblical is astounding!