I have tried to bury my intellect along with my name and to sacrifice all this only to the one who gave it to me. For no other reason I entered a religious order even though its duties and fellowship were anathema to the unhindered quietude required by my studious intent. Afterwards, once there, the Lord knows (and outside its walls the single person who ought to have known it knows so) what I undertook to conceal my name. But he forbade me to do so because he said it was a sinful temptation, and it surely was.

Juana Inés, “Respuesta a Sor Filotea de la Cruz” (1691). Translation by William Little.

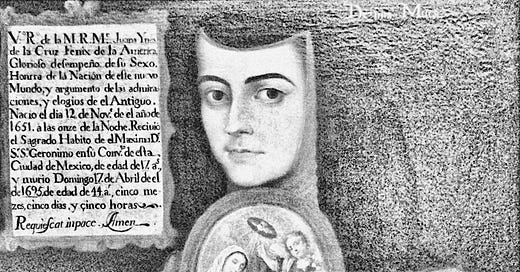

Juana Inés was born six years after Isaac Newton. As a queer woman in colonial Mexico, she played the same game at a much higher difficulty level (for example, Newton could get away with being publicly celibate without joining a religious order). We’ll never know how good she was, because most of her work was destroyed, unpublished, by the Church. She was thinking about optics—why do parallel lines look like they converge at a distance? She was thinking about the origins of variations within a species, including among humans. She was thinking about force and inertia—why does a top keep spinning after you let it go? Did she get anywhere? Somewhere, perhaps, a bit heretical? Unclear. All that’s survived is a few essays and a fair amount of poetry and fiction. Which has been more than enough to ensure her name will never be concealed again.

Her Respuesta a Sor Filotea de la Cruz is my favorite of the works of hers I’ve read. She’d gotten dragged against her will into a public theological debate, and then her opponent (a man writing under a woman’s name) had pivoted to attacking her life choices, as one does. “Why is a nun being an intellectual, anyway? Isn’t that hypocritical?” Her response is, in part, that being an intellectual wasn’t a choice. Baby, she was born this way. She gives an endearing series of anecdotes from her life about how compulsive a thinker she is. Even when she’d rather give her brain a break, she ends up analyzing whatever’s in her field of vision. Or her field of vision itself—ooh, it’s a sphere! So it creates spherical distortions at the edges. Is that why people used to doubt that the Earth was spherical? They thought it was an optical illusion?

I believe her, when she claims that she never wanted to be famous. She just wanted to learn and to write. She became famous because people didn’t think someone like her could exist. She had to do public exhibitions of her talents in order to get a patron. She had to write under her own name, and about herself, because people were always—always!—trying to take her books away to help her be more feminine. And she was an American, a Mexican, a colonial. To get published in Spain, she had to either pretend to be Spanish or be emphatically American. She’d been writing in a mix of Spanish, Latin, and Nahuatl since she was a child. She wasn’t going to write with her Americanness tied behind her back. So she needed to defend, too, the idea that Mexico could have something to teach Madrid. She needed to be herself, and loudly, or she’d be silenced.

Which is how she ended up posing for a portrait, even though it felt really weird.

She wrote a poem about it, which I’ve narcissistically decided to translate myself.

A SU RETRATO

Este, que ves, engaño colorido,

que del arte ostentando los primores,

con falsos silogismos de colores

es cauteloso engaño del sentido:éste, en quien la lisonja ha pretendido

excusar de los años los horrores,

y venciendo del tiempo los rigores,

triunfar de la vejez y del olvido,es un vano artificio del cuidado,

es una flor al viento delicada,

es un resguardo inútil para el hado:es una necia diligencia errada,

es un afán caduco y, bien mirado,

es cadáver, es polvo, es sombra, es nada.

English:

TO HER PORTRAIT

Behold a lie in vivid hue.

Ostentatious, artistic beauty.

Color pictures are a fallacy,

sneakily, subtly deceiving you.With this, my fans are trying

to excuse me from the wastes of time.

To shift me from the fleeting to sublime.

To annul aging, to defeat dying.Itself, it was a waste of time to create.

It’s a flower that the wind will rake.

A would-be obstacle to inevitable fate.It’s wrong. It’s a diligently crafted mistake.

As a portrait, it’s already obsolete. Too late.

Look closer: it’s corpse, it’s dust, it’s shadow, it’s fake.

I feel the same way. I don’t want my words to paint portraits. People are always so much bigger than a portrait can possibly show. A painting is a moment in time, pretending to be eternal, but words are even sneakier. If I tried to talk about every aspect of Juana Inés, at best I’d just trick you into thinking that you knew her, two dimensions with the illusion of depth. As she wrote (I forget where), we think that when we grow up we’ll know everything. We gradually realize that no, it’s impossible to fully know even one thing.

So I’ve limited myself to highlighting the themes in her life and work that I want to briefly point out in one of her plays, The Divine Narcissus.

The Prologue

The opening scene framing the play is more famous than the play itself. It’s a four-part argument among avatars of Europe, America, Christianity, and Zeal. Christianity metaphorically conquers Europe, while Zeal, in the form of conquistadors, more literally conquers America. Zeal wants to kill all of the natives, or at least erase their culture. Christianity stops him. I’m a conversation, not a conversion, she explains. Europe and America, like every other culture, were already stumbling towards Christianity before they ever heard of Christ. Our job is more to help them see that the God of Seeds, the God who dies and is reborn, the God whose blessed flesh we eat, does not actually require more human sacrifice. Our job is to get Europe and America talking to each other, teaching each other, rather than killing each other.

To prove her points, both about syncretism and about the ability of America to teach Europe, Christianity decides to put on a passion play in the form of a retelling of a Greek myth. Written in Mexico, to be performed in Madrid. Abstractions can ignore oceans, she explains.

The Play

Narcissus is Jesus. Once you see it, you can’t unsee it.

“God so loved the world,” says the most famous verse in the Gospels. But God is the world. All that is good in the world is a reflection of God. God loves Himself. “God so loved the world, that he gave his only begotten Son”—but Jesus is God. God died of love for a reflection of Himself.

Narcissus, in the myth and in the play, dies of love for his own beautiful reflection in the waters of the Earth. A nymph, Echo, tries to tempt him away from his passion. And fails. Echo is the Devil, and in the end, defeated, even she’s just a distorted repetition of the truth.

“Love is reckless,” Narcissus tells her. “It can make even a god mortal. But it’s my fate. I must love even those you call inferior. I must love even my own mortality. It would be pride to call it a lesser state of being. It is humility to acknowledge that I am the best I can be.” And Echo, helpless, echoes his words back to him.

He dies in agony, but in sure and certain knowledge of his resurrection. And so ends the play.

The Resurrection

That lying portrait is everywhere now. On 200-peso bills. In the Episcopal calendar of saints, as of 2022. In articles about feminism, about the power of religion, about the power of secular science in defiance of religion, about her sexuality, about her chastity.

It’s not her. She’s dead.

But she wasn’t trying to cheat death. She was trying to make the world richer, and she did in many ways. What she didn’t realize, at least at first, was that the most valuable gift she could give was pieces of herself. Not the whole of her, which is impossible. The wafer-thin slices we’ve been allowed have helped us to better understand and love (which are the same) ourselves and the world (which are the same). The portrait is a shadow, but a long one. A welcome shade in this too-zealous sun.

Love’s reckless leveling goes in the other direction, too, she writes in her poem Lysi, which kind of reads like her portrait writing a rebuttal to her attack on it. You can appreciate something bigger than you, without diminishing it. You can love someone, without claiming them.

Que mirarte tan alta,

no impide a mi denuedo;

que no hay deidad segura

al altivo volar del pensamiento.

Not even a god can stop us thinking.

As you might have guessed, I resonated with the inherent failure of trying to write a portrait of a person. And still we try... Well done, this one!