The Benefits of Walking Your Cynic

A profile of another star in the Godwin-Wollstonecraft-Barlow constellation.

John “Walking” Stewart did not believe in reincarnation. It was far too discrete a concept for him. There’s life after death, he wrote, but it’s not one-to-one. The river flows into the ocean, and the ocean feeds new rivers. So I’ll just say that it seems that quite a few of the particles that had been Diogenes of Sinope in 323 BCE seem to have later recollected in the form of an 18th-century traveling philosopher.

Dunce

Stewart’s childhood is an excellent demonstration of the evils of standardized education. His parents, being British and modestly wealthy, sent him to elite boarding schools from an early age. Stewart demonstrated a precocious talent for writing philosophy (“who wrote this for you?” was a frequent response to his essays). He played games and sports, and was also a young entrepreneur, engaging in various “illegal enterprises.” Whatever he set his mind to, he pursued diligently.

So naturally he was pronounced a “dunce” and “lazy.” See, at school you have to learn all sorts of things, not just philosophy, games, sports, and whatever black market shenanigans he was up to. He didn’t put any effort into the subjects that didn’t interest him, so that meant he was a bad student, which meant, student being his sole job description, that he was a defective person. His parents were advised to pull him out and get him a full-time job so that he could gain a “work ethic.” So sometime around age 14-16, he was shipped off to India to work for the East India Company.

What’s horrifying about Stewart being labeled a lazy dunce isn’t what it did to him. He was fine. He didn’t fully internalize it, rolled with the punches, and ended up living his best life. What’s horrifying is that this is done to almost everyone, and we don’t all handle it so well. We all had affinities and aversions as kids. Where they didn’t line up well with the standard curriculum, we were told to use our inherent strength of character to fix that—a task that is mostly impossible and mostly undesirable. What broke under the strain? Usually confidence. Either our character was defective, some part of us concluded, or we were utterly hopeless in some subjects.

Much later, people said to Stewart the same thing they say to me—“It’s easy for you to rail against standardized education. You didn’t need it. You were special. Most people aren’t like you.” I don’t think that’s right. Stewart and I were special only in that our childhood affinity was philosophy, which helped us realize what was being done to us while it was still going on, and come out somewhat intact. But there’s nothing special about being special. Most people are special. Most people have both unusual talents and unusual cognitive disabilities. But “special education” is stigmatized. It’s for deficient people. If they were better, they’d be in standardized education instead. No. Stop telling kids this. It doesn’t matter what words you’re using—your actions are speaking louder. We shouldn’t want our population to consist of standardized, interchangeable parts, so we shouldn’t keep shaving people down until they fit in the slot.

The Reluctant General of Mysore

Stewart and I have another thing in common—our first job out of school was in India. Stewart was put to work as a clerk in Chennai. He immediately began plotting his escape. He needed, he calculated, £3000 in savings to do what he really wanted to do—spend decades as a wandering philosopher. It soon became apparent that clerking wasn’t going to get him there, and also that the East India Company was terrible, working ultimately against the interests of both Britain and India. He wrote a scathing letter to company leadership, quit, and went to work for an Indian leader instead, Sultan Hyder Ali.

Or, possibly, he was captured and enslaved by Hyder Ali. Stewart, despite living one of the most interesting lives of all time, didn’t like to write or talk about himself. Almost everything we have of his life is second-hand at best, and accounts vary.

Hyder was a Muslim, of either Arabic or Punjabi descent. He had risen through the ranks as a soldier in another’s army to become the de facto ruler of the Kingdom of Mysore. If Stewart came voluntarily, it was to offer his services as a translator and interpreter, but he was soon pressed into military service as well. He saw a lot of fighting and got several scars. He got a dent in his head that never healed. But he also rose through the ranks, supposedly attaining a title that translated to “general.” Despite his savings goals, he distinguished himself from his fellow officers by not embezzling any of the money meant to pay those under his command. His well-paid troops were fanatically loyal.

He didn’t really want to earn his financial independence through violence, though, if indeed he was actually getting paid at all. When one of his wounds kept acting up, he asked permission to leave to get it treated. Hyder, knowing of the loyalty of his troops, didn’t feel safe saying no, but also didn’t relish the idea of his general getting an opportunity to defect. So he agreed, but sent along an escort with secret instructions to murder him as soon as they reached the border.

Stewart sussed this out, or was warned. During the journey out, he waited for his moment, then suddenly dove into a river, swam across, and ran away while the assassins were still trying to figure out how to react.

(My own Mysore story (#8), seems dreadfully boring in comparison).

It’s a lovely decade, I think I’ll walk.

Stewart found a better boss, another Indian ruler who I think was probably this guy, who was happy to have him do administrative work. He finished saving up. Then he walked home.

Now that he had financial independence, Stewart was in no hurry. He wanted to be back in London at some point, but he wanted to learn as much as possible along the way. He avoided vehicles whenever he could, and he didn’t take a particularly direct route. Years later, he arrived in London having spoken to people all over India, Persia, and Turkey. On the way, he’d developed a unique philosophy, influenced by Eastern pantheism and by Western materialism.

Stewart generally considered London his home base, but he kept on walking. He backpacked through a good chunk of the Northern Hemisphere, including the U.S. and Canada. Almost everybody started calling him Walking Stewart, which is better SEO.

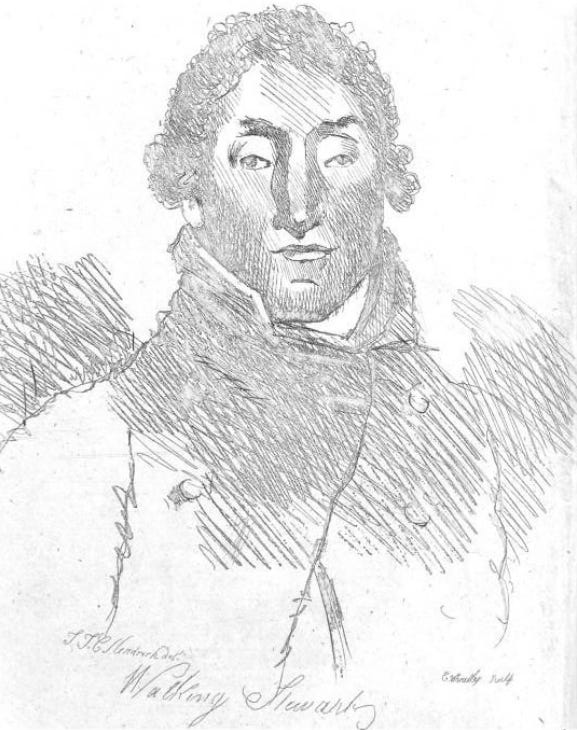

He typically wore, by all accounts, a really weird outfit. I wish we had a portrait. He referred to it as “Armenian,” but I suspect its actual origin was “everywhere.” His souvenir from anywhere he visited, I think, was the most durable article of clothing he could get his hands on. Often this meant something military. So he was probably dressed in an amalgam of uniforms from around the world. (Maybe Armenian was a pun on army? Army-nian?)

Where Diogenes pared down his possessions to the bare minimum, giving away his bedroll after he realized he could just use rolled-up clothes as a pillow, Stewart was more Epicurean. He optimized carefully for the life he wanted, which meant traveling light but with high-quality, utilitarian choices in what he took with him. He wasn’t ideologically committed to asceticism. When he realized that his lack of social status was making it harder to get his message out in London, he took steps to rectify this. The East India Company had taken over the territory of his last employer in India. He successfully argued that this meant they had assumed his debts, and owed him a mountain of back pay. He collected, put most of it into annuities, and spent the rest getting a fancy apartment, full of mirrors reflecting mirrors and exotic art. That let him host parties that local philosophers would actually attend.

He still wore the “Armenian outfit” though. It was such a good conversation starter.

Syncretic Cynicism

Stewart’s philosophy starts in the same place as Diogenes’s. Near the beginning of The Apocalypse of Nature, Stewart writes

All things that make an impression upon the senses of animated matter, contain in themselves a power or propensity to motion, which power is augmented or varied by the different combinations of bodies.

Matter, which in its dissolution, separates, can never be annihilated, and though it may disperse into an infinity of small particles, which, making no impression upon the gross organs of sense, may disappear, yet must continue to be in the great mass of existence; to which, as it is impossible to suppose a beginning, it is also impossible to suppose an end, and it may, therefore, be called eternal.

As a strict materialist, he concludes from the mixture of materials that everything is mixed together, because the material is all there is. A body can create a spirit, he says, but a spirit cannot create a body. So those particles are the source of spirit. The boundaries between minds, between ideologies, and between concepts are real, but fuzzy and shifting, just like the matter that creates them.

From these principles, he derives karma and dharma. Everything is connected, so the good and bad you put out into the world will come back to you. Unnecessary violence (his example is swatting a fly instead of shooing it away) reverberates and rebounds. Kindness does the same. And when you die, your particles merge with the universe…so be kind to the universe. Make the world better for the billions of animals, humans included, who you will one day be a part of. It’s in your own self-interest.

Reminding me of the poem sung in Beethoven’s Ode to Joy, which he may have read, he says this proves that we all have the capacity for goodness. We all have the capacity to love ourselves—that’s what joy is. Animals, he says, are a musical instrument that can appreciate its own music, and joy is our favorite chord to hear. And if we can love ourselves, we can love everyone and everything else, as long as we remember that the boundary between self and other is fluid and porous.

Speaking with yogis, imams, and everyone else within a few years’ walk of London gave him a truly unique voice. It also taught him the emotional skills he needed to survive this lifestyle. “Avoiding moral contagion,” he said, “by behaving politely to the vulgar, complacently to the angry, humbly to the proud, and wisely to the foolish, has conducted me over the world, through the constant shock of customs, habits, tempers, and opinions, with scarce a serious personal quarrel.”

Only Connect

There’s something gratifying in reading all of these revolutionary-era philosophers who hung out in London. They’re all very different in temperament and perspective (not that that stops me from over-identifying with whoever I’m writing about). By the standards of the time, or even of each other, they were weirdly intense and intensely weird. But they were all actually listening to each other. You can see them learning. Godwin’s essays in Thoughts on Man on education, I now think, must been influenced by Stewart’s story. Stewart got more feminist after speaking with Wollstonecraft, and more anarchistic after speaking with Godwin. And Barlow, consequentially, may have learned from Stewart that his religious prejudices were misguided.

Appropriately, Londoners wrote that Stewart seemed to be everywhere at once. The popular joke, which may have shaded into actual legend, was that there must be three of him. And other travelers returning from India sometimes reported that he was there, too, still trapped in Mysore.

What Paul Erdős did for mathematics, using airplanes, Stewart did for philosophy, just by walking. He demonstrated his own thesis, spreading and intermixing the thoughts of many lands. And the cross-pollination he started didn’t end with his death. The next generation, the Romantics, grew up with him as their role model. As soon as they could, they too began traveling the world, seeking wisdom, joy, and themselves. The river became the ocean, and the ocean became many rivers.

William Wordsworth’s long autobiographical poem, The Prelude, memorializes Stewart (probably).

Close at my side, an uncouth shape appeared

Upon a dromedary, mounted high.

He seemed an Arab of the Bedouin tribes:…

the stone

(To give it in the language of the dream)

Was "Euclid's Elements;" and "This," said he,

"Is something of more worth;" and at the word

Stretched forth the shell, so beautiful in shape,

In colour so resplendent, with command

That I should hold it to my ear.…

The one that held acquaintance with the stars,

And wedded soul to soul in purest bond

Of reason, undisturbed by space or time;

The other that was a god, yea many gods,

Had voices more than all the winds, with power

To exhilarate the spirit, and to soothe,

Through every clime, the heart of human kind.…

Far stronger, now, grew the desire I felt

To cleave unto this man; but when I prayed

To share his enterprise, he hurried on

Reckless of me: I followed, not unseen,

For oftentimes he cast a backward look,

Grasping his twofold treasure.…

He, to my fancy, had become the knight

Whose tale Cervantes tells; yet not the knight,

But was an Arab of the desert too;

Of these was neither, and was both at once.…

This semi-Quixote, I to him have given

A substance, fancied him a living man,

A gentle dweller in the desert, crazed

By love and feeling, and internal thought

Protracted among endless solitudes;

Have shaped him wandering upon this quest!

Nor have I pitied him; but rather felt

Reverence was due to a being thus employed;

And thought that, in the blind and awful lair

Of such a madness, reason did lie couched.

Stewart lived to the age of 75. He was quite comfortable, when he chose to be, because he’d bought lifetime annuities at a bargain price. His peers were only living to about 60, and the annuities were priced accordingly. They didn’t take into account that he was a vegetarian and teetotaler, and didn’t get into personal quarrels. And, of course, enjoyed long walks.

Bonus: More Diogenes Particles

Stewart, in the middle of a paragraph in Apocalypse about honesty and freedom of speech, unexpectedly throws in a couple of sentences about preventing the debasement of currency, the crime Diogenes and Newton were convicted of. There’s definitely something deeply philosophical about invisibly altering the accidents of a signifier.

Here’s one of the very few stories Stewart himself told about his travels. While on a ship leaving India, a storm approached, and the superstitious sailors thought he, as the only infidel on board, must be a jinx. They decided to throw him overboard, so he negotiated. “Rather than make yourselves infidels by committing murder,” he suggested, “just trap me in a chicken coop and hoist it above the deck. That way the storm will go after me and spare the ship.” And so, suspended in the air, surrounded by people who’d just almost killed him, he meditated through the storm. “Diogenes only lived in a barrel,” a relative of his commented after.

The broad strokes of Stewart’s life are a lot like those of Diogenes, but in a different order. Diogenes ran a mint, then became an ascetic philosopher, then a slave. Stewart was a slave in Mysore, then became an ascetic philosopher, and then got rich. Diogenes was born in Turkey, then traveled to Athens. Stewart was born in Britain, then traveled through Turkey.

Nothing written by Diogenes has survived. Stewart was always very concerned that this would happen to him too. Most of his books have a preface saying “If you like this book, please consider burying it somewhere secret and only revealing the location on your deathbed, so that even if authoritarians take over the world they won’t be able to burn all the copies.” This is one of the ways the character in Wordsworth’s poem can be identified as Stewart— “the Arab with calm look declared/That all would come to pass of which the voice/Had given forewarning, and that he himself/Was going then to bury those two books.”

Diogenes was “The Dog.” In his obituary in the London Magazine, Stewart, who had often seemed to be in three places at once, was referred to as Cerberus, after the three-headed dog of Greek legend.

for he was ever all in all! – Three persons seemed departed in him. – In him there seems to have been a triple death! – He was Mrs. Malaprop’s ‘Cerberus – three gentlemen at once!’

Oh, this is lovely. After reading some Byron, I've been kind of on a "Year Without a Summer" kick. (I wonder what Walking Stewart was doing in 1816.) In any case, I loved your articles about Godwin!

Walking Stewart reminds me of the stories my dad used to tell about Woody Guthrie, and later, the stories about the writers of the Beat movement. I guess the peripatetic, philosophically syncretic lifestyle is fit for artists, Cynics who happen to be accountants, and holy fools alike. (At the very least you need an interesting outfit.) I've read a lot of travel writing where the prevailing theme seems to be a person kind of imposing themself on a new place, or a person asking a new place to change them. From your piece, I suspect Stewart didn't do this in the same way.

Also, please never stop talking about education. Holt was right. For every kid who gets out, there are many more who get hurt. I'm glad it tends to naturally come up.