The Philosopher's Tarot: Late-Stage Epicureanism

In capitalist panopticons, the garden walks all over you.

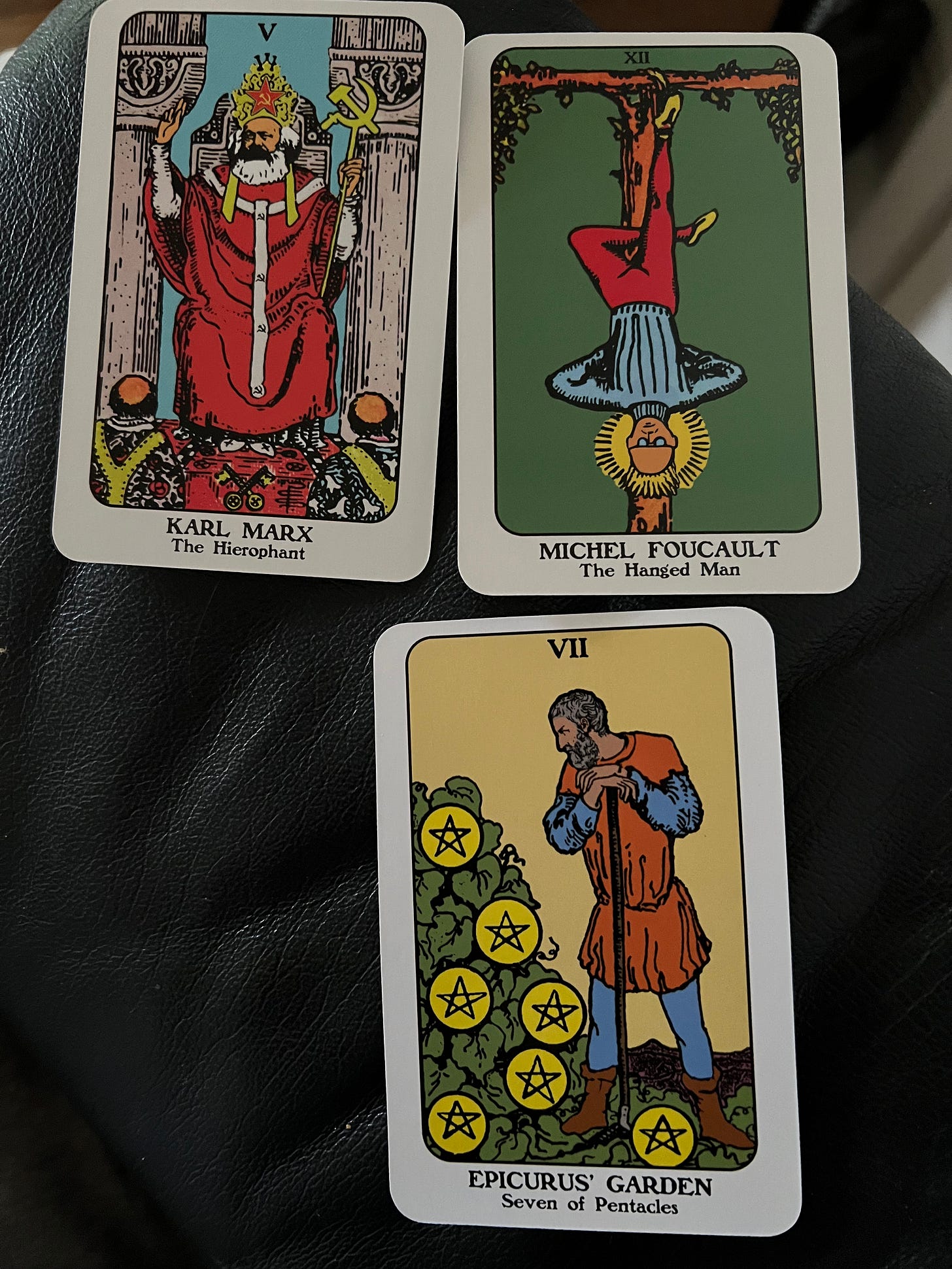

Here’s today’s random draw from that tarot deck I was given.

I’ve structured my random draws to try to get two philosophers and one concept, and so far my methodology is 0 for 2. Last time I only got one philosopher. This time, the concept card, Epicurus’s Garden, is barely separable from Epicurus himself, so I really have three.

Epicurus and his garden have had an interesting evolution. The primary definition of “epicurean” today is “hedonistic, luxurious, refined.” But Epicurus himself condemned most forms of luxury, preaching a kind of asceticism. Epicurean (and hedonistic) used to mean something very different.

Epicurus taught that the purpose of life was to maximize comfort and minimize suffering. He also taught that the most efficient way to achieve that was to purge all unnecessary desires and fears from yourself. When we do work we don’t enjoy, it’s either out of a desire for fancier stuff or anxiety over the future. If you can instead cultivate simple tastes, and a calm acceptance of the inevitability of death, you can spend more of your time chilling in a literal or metaphorical garden.

Our concept of how to most efficiently seek pleasure has changed since his time. “If drinking expensive wine doesn’t make you happy, have you considered…drinking even more expensive wine?” Or, put another way, we’ve entered late-stage capitalism. That’s right, we’re doing a Marxist reading of Epicurus now. The cards command it.

Marx himself didn’t use the term “late-stage”. His stages were coarser-grained: slavery, then feudalism, then capitalism. It’s more in the 20th century that Marxists began to slice the capitalism stage up further. Let’s start with the coarse-grained story.

Epicurus’s original garden was built on slavery. In his time, almost everybody either owned a slave or was a slave. Nobody had a lot of slaves—the largest number recorded is 50, and low single digits were much more common. So if you were a free person (yes, there were women in the garden, too) and wanted to spend your life in comfort, all you needed to do was make sure your wants were few enough that you and a slave could live off of only the slave’s labor. Two can live about as cheaply as one, so this is very doable. If you’re ambitious, though…there weren’t many mechanisms that let you do nothing and get rich and famous anyway.

This changed in later centuries. Romans refined the Greek class system—they had slaves, but they also had plebeians, who were considered free, but still expected to work for a living. They ditched most of the mechanisms Greece had used to prevent wealth from being overly concentrated, so they ended up with more people rich enough to achieve an immortal legacy without having to sweat for it. As in Greece, Roman slavery wasn’t (primarily) built on racism, which meant slaves could have white-collar jobs without threatening the ideological underpinning of the institution. Epicurus thought anyone who spent too much worrying about what the Gods thought of them was doomed to unhappiness. But in Rome, you could have an enslaved architect design a temple and a team of hundreds built it, all while you hung out in your garden.

Enslaved Jews, it turns out, didn’t actually build the Egyptian Pyramids a couple thousand years earlier. The Pyramids were built by paid workers, who could and did go on strike for better conditions or higher pay. Enslaved Jews probably did built the Roman Colosseum, though. The Colosseum was built using the loot from the sack of the Great Temple, and while we don’t have a record of who designed and built it, the timing and the Roman love of humiliating their enemies point at Jews in particular.

Rome, in this way, was a half step forward from Greece in Marx’s grim march toward capitalism. Even before we got to something as direct as feudalism, we were developing a class structure that allowed for a select few to live a life of pleasure without needing much modesty to make it viable. If you were a rich patrician, the only potential obstacle between you and bliss was an ideology that put anything above bliss. A work ethic, say, or a belief in equality. So Epicureanism, the ideology that puts bliss first, became the ideology most suited to a life of luxury.

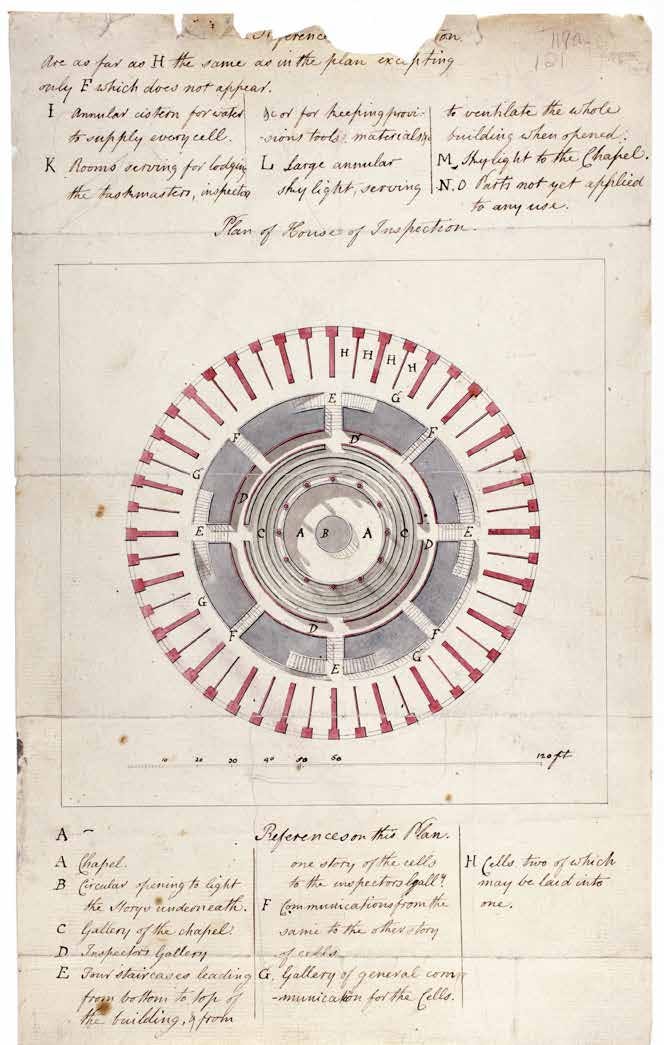

One problem with shaping your social structure like a pyramid is that as it scales up, the people on the bottom outnumber the people on the top by a greater and greater ratio. Revolution becomes harder and harder to stave off with force alone. The 18th-century Epicurean philosopher Jeremy Bentham came up with a solution for this kind of dynamic: don’t structure your society like a pyramid, structure it like the Colosseum.

The idea of the Panopticon was that if a prison warden could potentially be watching you at any time, prisoners didn’t need to be actually watched all the time in order to be kept obedient. They just needed to not be able to tell when they were being watched. This architecture, Bentham thought, would allow for a much higher ratio of prisoners to wardens. The concept could be extended, he wrote, to other kinds of coerced labor too.

Bentham was all for this as a literal design, and after his death it did go on to influence the architecture of some poor-houses and factory floors. It’s also caught the imagination of later philosophers as a metaphor/symptom. Most famously, by our third card of the day, Michel Foucault.

Foucault, one of the more reliably pessimistic modern philosophers, saw almost every institution as an extension of slavery by other means. His stages of society, as described in his 1975 book Surveiller et punir : Naissance de la prison, were torture, punishment, discipline, and finally prison. All of these were increasingly sophisticated means of keeping laborers docile in the service of the elite. Most of us are in one sort of prison or another, by his definition. Officially, about one percent of the U.S. is incarcerated, but Foucault extends the “carceral state” to include school, the military, and industry. (I criticize this attitude here).

Sustaining this level of exploitation requires a whole bunch of different panopticons, from literal architecture to the surveillance state to ideologies. Ideologies are panopticons when they drive people to quasi-randomly single out one “main character of the day” to jointly punish. They also can sustain a power imbalance by providing justification for it—the warden is watching from inside your own brain. Uncertainty about the actual rules can actually improve an ideology’s effectiveness in promoting compliance, in a panopticon-style dynamic.

While I was researching possible followups to my Korah essay, I came across a random blogger who, at least in how he chooses to present himself in his own Korah post, seems to be my exact ideological opposite number. Michael Zarling is (or was in 2019, anyway, I’ve only read the one post of his), a devout Lutheran and young girl’s soccer coach. He does me and Foucault a favor, really. He converts the subtext I called out in the Talmud, and Foucault in society, into plain text. Here’s some key lines from his post, The Punishment of Korah.

For warm-ups in our school gym, I’ll have them do monster laps, which are running up the steps, across the mezzanine, down the steps and around the gym floor. Already at our first practice, I will warn the girls. If I see them roll their eyes, they get another monster lap. If I hear them sigh, they get another monster lap. If I even think I saw them roll their eyes or think I heard them sigh, they get another monster lap. And if they disagree with what I think I saw or heard, they get two more monster laps.

I am the coach. I will not put up with eye rolls, deep sighs or disagreement. It is disrespectful of the coach. It is grumbling against a leader. The result is more monster laps.

God is God. He does not put up with jealousy, disagreement or rebellion. It is treating the Lord with contempt. It is grumbling against God and his appointed leaders.

…

We learn from the account of Korah and his rebellious followers that God is patient. But, we should never mistake his patience with acceptance. He is merely allowing us time to repent.

If we think that grumbling against our pastor, child’s teacher, President of the United States or whomever isn’t that big of a deal, then think again. If we think we don’t have a problem with grumbling … that is proof we do.

…

When we don’t see the need for confession and repentance, then we are putting ourselves in danger of being punished like Israel of old.

…

We should never ask, “Why does God deal so harshly with sin?” Instead, we should thank God that he has not dealt with us harshly, as our sins deserve.

Here we see how flexible an ideology of rigid authoritarianism can be! This one justifies the petty tyrannies Zarling enjoys visiting on teen and pre-teen girls, the institution of school, and even the bizarre un-American notion that one should never criticize the President of the United States. The overarching conceit is Foucault’s discipline—the message that we are making ourselves more virtuous by suppressing even the desire to rebel.

Zarling incentivizes us by converting the story of Korah into a panopticon. The lesson, he says, lies in the fact that Korah wasn’t punished right away. Only after he refused multiple opportunities to submit was he subjected to divine wrath. This shows us that just because it seems like we’re getting away with it, it doesn’t mean it’s safe to keep transgressing. He cites 1 Corinthians 10, where Saint Paul writes that right when you’re feeling safe, that’s when God might decide to make an example out of you.

This culture of fear and consumption, per the Epicurean-Marxist-Foucauldian school, is what allows billionaires today to live in luxury at the expense of almost everyone else. Doing anything weird is just too scary—eventually God, the police, or society will come down hard on you. Safest just to accept the norms as presented to you, and don’t even try to ask who created them, or how they benefit.

I don’t exactly endorse the universal application of this school of thought that I’ve kind of just made up. But it does seem like a story worth telling, among other stories. So I’ll call this experiment a success, so far.