Is it weird that our national anthem is about compulsively checking and rechecking whether something terrible has happened, without being able to do anything about it?

A Low-Key Thriller

During the war of 1812, a Maryland doctor was taken prisoner by the British. It wasn’t clear if or when he’d be set free. His friends decided to try to negotiate for his release. One of them, a wealthy lawyer named Francis Scott Key, drew the short straw. He requested and was given formal approval by President Madison, then traveled to the British ship in the Chesapeake Bay where Dr. Beanes was being held.

Naval invasion across a wide ocean, or even a large bay like the Chesapeake, was a tricky business to coordinate. If you gave captains too much individual autonomy, the fleet would get divided and be vulnerable to a concerted enemy. But without instant communication, you couldn’t give up-to-date orders. The British solution was to give orders in the form of long if/else programs, specifying the exact conditions where each ship was to do X or Y.

When Key came aboard, they were at this line of code: “Sneak attack Fort McHenry. If you capture it within one night of revealing yourselves, continue on and capture Baltimore. Otherwise, retreat.” Key overheard this, which added even more stress to his situation. He’d just come from Baltimore. It was now possible he’d return to find the city in flames.

Key lawyered on. The British refused to ransom the doctor, but Key presented letters from wounded British prisoners of war thanking American doctors for treating them. The least they could do in return, the British eventually agreed, was to let one go free.

Negotiations concluded, things got awkward. They knew he knew about the sneak attack, which was still a few days away. Key knew way too much to be allowed to go home right away, but he was there under the official protection of his government, so they didn’t want to take him prisoner. So instead they just tethered his boat to one of the other ships in the invasion fleet, the aptly-named HMS Surprise, and posted guards at the tether. Key was back on his own vessel, but he was now an unwilling participant in the assault on Fort McHenry.

The Rockets’ Red Glare

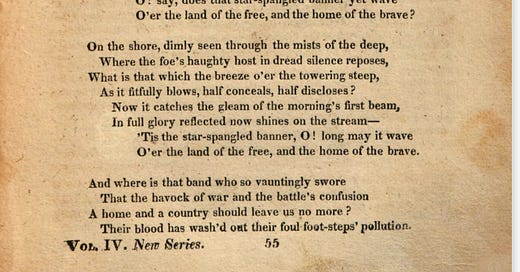

When Surprise, along with 15 other ships, began bombarding the fort, Key watched, helpless. If the American flag was taken down, he and the invasion fleet would know the fort had been taken, and with it Baltimore’s best chance of survival. The sun set, but of course he couldn’t sleep. Not only were explosions keeping him awake in the normal way explosions tend to do, they were also intermittently shedding light on the flag. He had to keep checking whether it was still there. Like scrolling infinitely through bad news, or refreshing the page with the latest vote counts, it was a pointless but irresistible compulsion.

When the sun rose, the flag was still there. Then he would’ve seen it being lowered, and maybe had a moment of despair. But it was only being lowered to be replaced by another, much bigger American flag. The flag he’d been watching was the flag for nights and storms. This new flag was raised every morning, for reveille. The fort had held. The fleet would release him and Beanes, then follow the else branch of its orders and retreat.

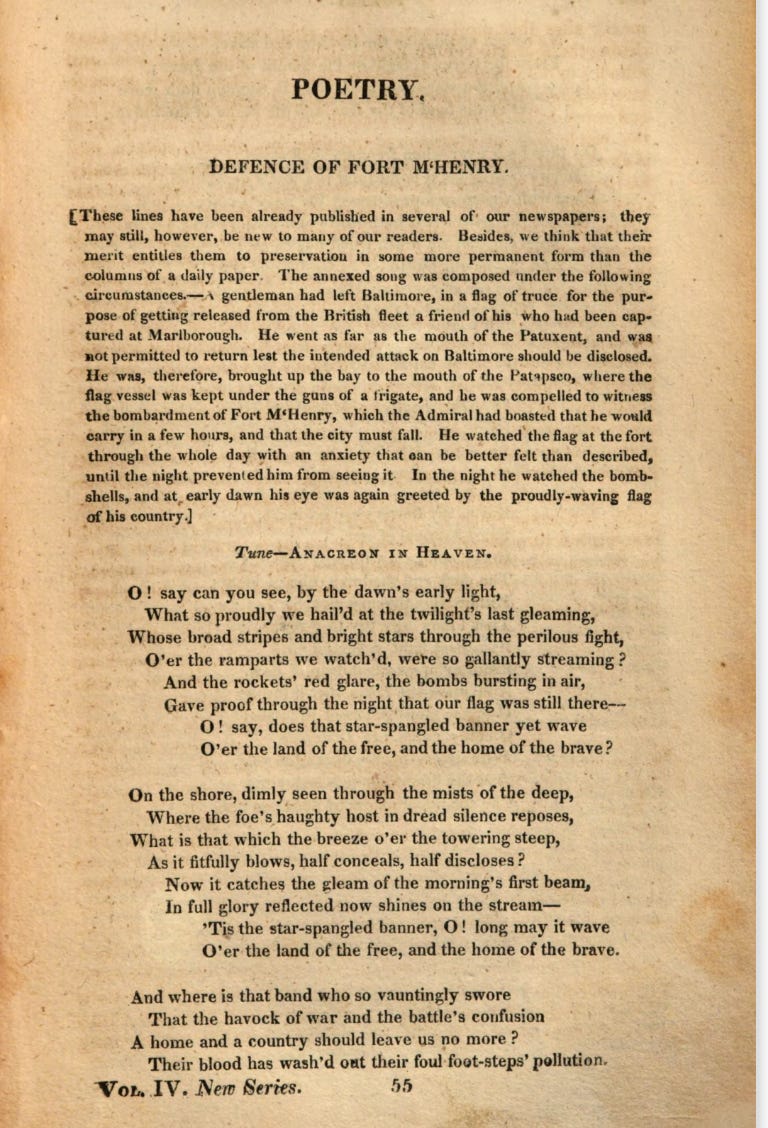

Despite the name, Key wasn’t a songwriter. Still, he had to somehow process this harrowing, then ultimately triumphant, experience. So he wrote new lyrics to an existing song. He eventually got them published in newspapers, and then a magazine called The Analectic, which published it with an introduction that was probably written by the magazine’s editor Washington Irving.

The song gradually got popular enough that the lack of an original tune started to be a problem. Different people were coming up with different tunes, which must’ve led to some dissonant renditions. President Woodrow Wilson enlisted a team of five musicians, each with a different musicological specialty, to collaborate on a definitive original melody. The result became, and remains, our official national anthem.

Should It Be?

Probably not forever. Many country’s anthems express goals more lofty than “remain a country”. It’s appropriate in that way for a young one like ours, facing an uncertain future. Eventually, I hope, we’ll outgrow it.

In other ways, we already have outgrown it. It’s a song about the land of the free, yet Key owned slaves, and his law practice implicated him in preserving the institution. One verse of his song, one we typically don’t sing, seems to mock the enemy for their practice of allying with American slaves, giving them a chance at freedom if they fought at their side. If we’re tearing down the statues of slaveowners, maybe we should do more than just usually-censor this one?

Also, it really is a song about doomscrolling. That wasn’t just clickbait. It’s a song about watching o’er the ramparts while other people fight, feeling anxiety and then relief. That’s certainly a big part of our national mood, but is it really the part we want to center? If Francis Scott Key has to contribute to our national identity, I’d rather we highlight the part where he rescued a friend, armed only with his own bravery, a flag of truce, and documentary evidence of our moral treatment of prisoners. Not the part where he couldn’t sleep.

I don’t have a good suggestion for a replacement. All the good anthemesque songs I know of are too associated with one particular group or another. And, like Key, I’m not a composer. So I’ll just wait, watch, and hit refresh.