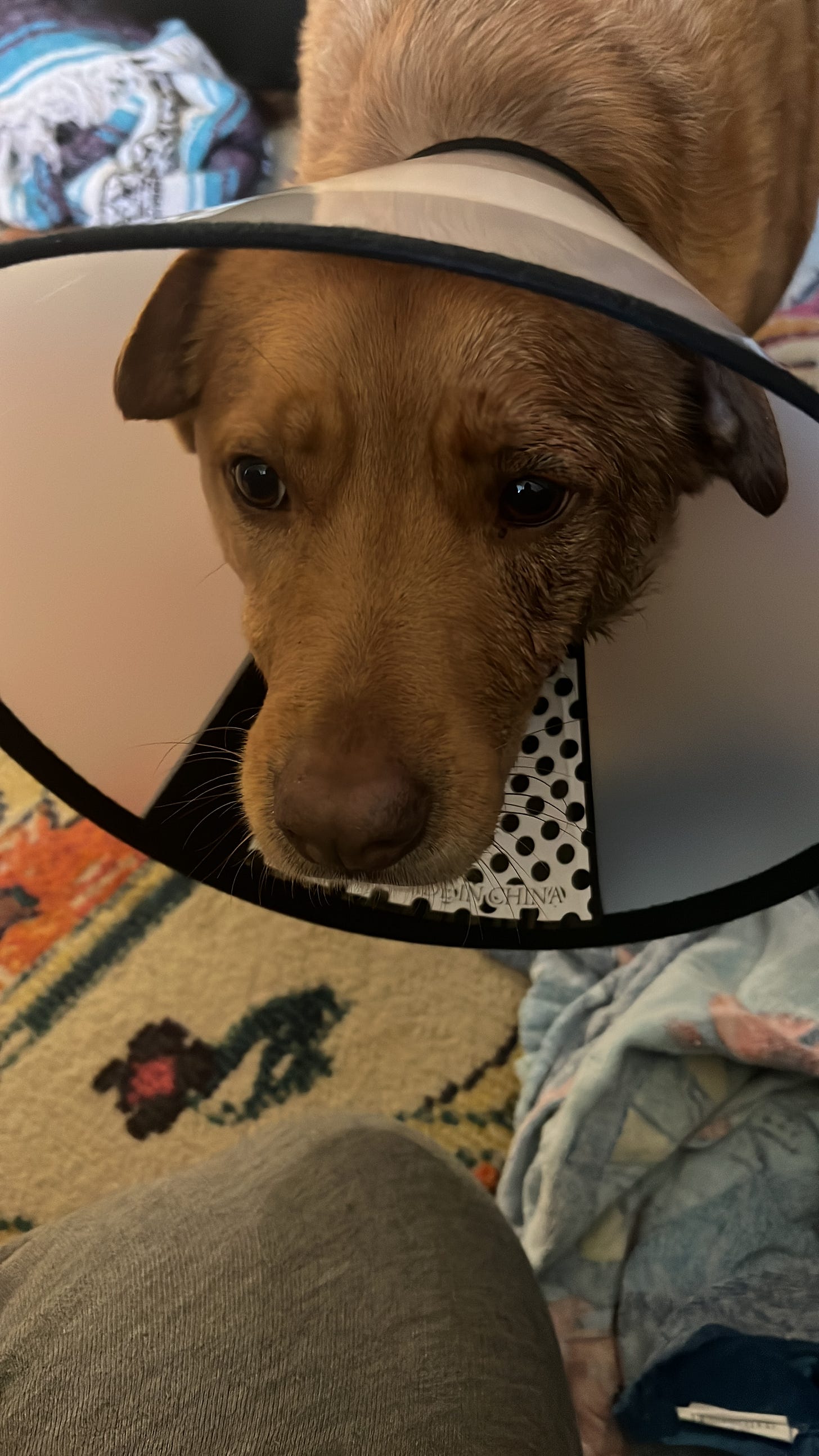

One clear day last fall, I was sitting with my dog in our backyard. I’m not usually one for admiring the scenery, but that day I was really struck by the changing colors of the leaves. I sat there calmly for a while, just looking. Then I had a kind of sad thought—my dog almost certainly wasn’t able to appreciate the sight. Dog eyes are much worse than humans at distinguishing colors, and dog brains treat sight as only the third-most-important sense, after scent and hearing. I’d seen a mouse successfully hide from him by freezing in place in plain view. I turned to look at him, and saw that he was also sitting there calmly, but with his nose working more than I’d ever seen before, twitching back and forth, absorbing scents the breezes were bringing by as they shifted. We were in the same environment, and we were each glad of the other’s company. At the same time, we were in different worlds.

Some philosophers would say we were in the same place, but a different umwelt. I first learned about this word from an XKCD cartoon, one of his many elaborate April Fools day features. It’s a different comic depending on everything about the viewer that’s detectable over the internet—try expanding and shrinking your browser window, for example. There’s a single, basic reality underlying every experience, but that commonality doesn’t always matter the same amount.

In different umwelten, you’re not merely perceiving the same objects differently. You’re slicing up your observations into different concepts. For example, humans tend to think of things as either contaminated or pure. Try spitting into your own drink. That same spit was going to mix with it in a second anyway, but “a drink someone’s spat in” is a fundamentally different object. My dog’s a neat freak by dog standards, but he’d never make that mistake.

Umwelt is a modern term, but people see antecedents of it in writing going back much further. Josef Pieper, a 20th-century philosopher and “philosophical anthropologist”, reads Plato and Aristotle as saying that human reasoning lets us, uniquely, step out of our umwelt into the base reality of the welt. Pieper agrees. He invokes intuition — how could a creature confined to a single umwelt come up with the concept of umwelt? Unlike dogs, we’re not confined, Pieper says, because of Spirit.

Spirit, it might be said, is not only defined as incorporeal, but as the power and capacity to relate itself to the totality of being. Spirit, in fact, is a capacity for relations of such all-embracing power that its field of relations transcends the frontiers of all and any “environment.” — Pieper, Leisure: The Basis of Culture.

For Pieper and Plato, the “base reality” or welt is not the physical world. For Plato, it’s the world of concepts. Pieper, following in the steps of Thomas Aquinas, folds that into his own Catholic dualism.

The term umwelt itself comes out of a school of thought that inverts this relationship—concepts, or semiotics, are an idiosyncratic layer on top of an objective physical base reality. That school is just as old as Plato’s. In Ancient Greece, this controversy was known as Platonic Idealism versus Diogenes’s Cynicism. Our modern meanings of “idealism” and “cynicism” are distinct from these terms. They come from identifying idealism with certain specific concepts, like spirituality and ideology, and cynicism with skepticism concerning those concepts’ universality.

Diogenes: Sifting the Bones

Diogenes was a contemporary of Plato, born about 2,400 years ago in what is now Turkey. He fled, or was exiled, to Athens for messing with coins. He was either defacing or debasing them, it’s not clear. Either would be on-brand.

He wrote a lot, but we don’t think anything he wrote has survived to the modern day. There are some essays with Diogenes’s name on them, but they were probably written later. We know his philosophy from his students, and their students, and also from a sketchy collection of personal anecdotes compiled centuries later.

In some ways, Diogenes’s philosophy could’ve been a better fit for Aquinas and Christianity than Plato’s. Diogenes was an ascetic, shunning material possessions like a member of a religious order might. He preached a certain kind of humility. In one anecdote, Alexander the Great comes across Diogenes squinting theatrically at a pile of bones. Diogenes tells him that try as he might, “I can’t tell the difference between your father’s bones and those of a slave.” Sounds a lot like the Christian memento mori. (As far as I know, this insight is original to ChatGPT, although it’s as hard to sift apart the various sources of its training data as it is to separate the bones of different people.)

In other ways, his Cynicism is antithetical to most Christian thought. An anecdote has Diogenes criticizing people for bowing and prostrating themselves before the Gods. “Divinity is everywhere,” he says. “Think of what a disrespectful gesture you’re making to the divinity directly behind you.”

The core of Diogenes’s teachings seems to have been that everything is mixed together. Nothing is fundamentally different from anything else, when you go deep enough. His cosmology was basically Carl Sagan’s “we are all star stuff.” According to the same historian who compiled the anecdotes,

The following were his principal doctrines; that the air was an element; that the worlds were infinite, and that the vacuum also was infinite; that the air, as it was condensed, and as it was rarified, was the productive cause of the worlds; that nothing can be produced out of nothing; and that nothing can be destroyed so as to become nothing; that the earth is round, firmly planted in the middle of the universe, having acquired its situation from the circumvolutions of the hot principle around it, and its consistency from the cold.

Everything around us, from the sacred to the profane, comes originally from uniform hydrogen gas that collected in a vacuum, and was then transformed by being heated and cooled. Also, almost everything comes, more immediately, from other matter that’s been partially broken down and reconfigured. Everything is mixed together. Everything has trace amounts of everything else. So how can anything have an intrinsic essence? No thing is pure and deserving of worship. No thing is inherently taboo.

The word “cynic” comes from the Greek word for “dog”. It’s a cousin of “canine”. Historians aren’t sure why Cynics were called that, though. To which, I’m like, have you met dogs?

Dogs Are Cynics

Dog noses are built differently from ours. The tiny particles whose analysis we call “smelling” are trapped there, not sucked into the lungs or breathed back out. This lets them use a series of quick sniffs to detect very faint smells, and tiny changes in their intensity. A large part of their brain seems to be dedicated to interpreting smell, in the same way humans have a large visual cortex.

Interacting with the world via scent means that you’re intrinsically aware that nothing is created or destroyed, just transformed, mixed, and incompletely separated. When a dog follows a scent trail, that dog is sniffing in tiny particles of its prey the whole time. The dog isn’t going from where the prey isn’t to where it is. It’s going in the direction the prey is more densely concentrated.

This aspect of their umwelt can lead them to make mistakes a human wouldn’t. A dog might see a toy being moved from a place they can access to another place, visible but out of reach. He still might check the original spot to see if the toy is there too. A popular “intelligence test” for dogs is to have them watch you put a treat underneath a washcloth, then tell them they’re allowed to eat it if they can figure out how. Dogs often take a while to come up with the idea of lifting the cloth up to get at the treat. They’ll first try digging through it, trying to stick their head through it, or even tunneling underneath it. It’s counterintuitive, to them, to treat a washcloth like a single discrete object. It’s more like a region where the air is denser.

Generally, though, their worldview seems to work for them. It’s not right or wrong—it’s more useful than ours for continuous reasoning and less useful for discrete reasoning. We humans can’t observe trace elements of things, so we build our cognition and our houses around the discrete. Dogs build their cognition differently. My dog is pretty good at learning from his mistakes, and part of his process involves thoroughly sniffing the scene of the snafu. I have no idea how this helps, but it does.

Diogenes, by almost all accounts, was a dog person. I think he observed them, empathized with them, got the core of his philosophy from them, and cited his sources. Then, people made fun of him for that, and so he owned the label. “Sure,” he says in anecdotes. “I’m loyal like a dog. I flout human taboos like a dog. Give me food, and I’ll only bite you when you need to be bitten for your own good.” It turned into a schtick, and his students kept it going for another generation (the generation after that called themselves Stoics instead).

Meta Umwelt

Dogs spend even more time thinking about us than we do thinking about them. If they had abstract language, I wonder how they’d describe our umwelt. If they (or a species descended from them with similar senses) had theoretical physics, I wonder if they’d find quantum mechanics mind-boggling for the opposite reason that we do. We intuitively expect everything to be made out of solid little balls bouncing off of each other. They’d intuitively expect everything to be made out of density gradients. Quantum mechanics is the study of the scale where neither of these intuitions really works.

Does our abstract thought liberate us from our umwelt, or does it take place in a meta umwelt, still shaped and limited by the accident of our physical form? The distinction verges on meaninglessness, or at least unfalsifiability. We can never know of anything we can never know.

I find it more exciting to think of myself as living in one umwelt among many. There are so many worlds, not just out there in the infinite vacuum, but overlapping and coexisting with mine and yours. Empathy with other animals is a window, one through which we can catch tantalizing and enlightening glimpses into a universe we can’t fully apprehend.

Bonus: The Debasement of the Ideal

There’s two kinds of coins. One, “commodity money”, gains its value from the material it’s made of. A solid gold coin that’s been engraved with a picture of a ruler is valuable because of the gold part—the engraved picture of the monarch improves its ability to be used as a medium of exchange by acting as a seal of authenticity. In the modern day we mostly use “representative money,” which gains its value through convention—a check backed by a bank account, a dollar bill backed, ultimately, by the fact that you can pay taxes with it, or a bitcoin “backed” only by consensus.

Commodity money has certain advantages. It retains most of its value even in places where nobody recognizes it, as long as there’s some use for the material. Its main disadvantage vs. representative money is the cost of scaling it up. But also, it’s more vulnerable to a corrupt mint. Diogenes’s father was in charge of their city Sinope’s mint. Archaeologists found a pile of coins in Sinope that had been defaced around the right time period. Most of these defaced coins had less-valuable materials mixed in with the rare metals. In one possibility, Diogenes and/or his father were doing this in secret, enabling them to embezzle metals while still meeting their quota. Then they were caught, and all of their coins were defaced so that people wouldn’t be fooled by them. Representative currency isn’t as vulnerable to this kind of attack, although you still see the legacy of it in modern coin design, such as the beveled edges meant to make it obvious if someone shaved a bit off.

It’s also possible that their crime was the defacement. Destroying a bunch of coins can lead to rapid deflation, which is about as destabilizing to the economy as the reverse. It might’ve been an act of rebellion, rather than larceny.

Diogenes supposedly guessed, more or less correctly, that all matter had coalesced from gas within a vacuum. Much later, the mechanism for this process was first described by Isaac Newton. In a coincidence I don’t know what to make of, Newton was also convicted of the same crime of secretly debasing the coinage while in charge of the mint. Unlike Diogenes, though, he was later able to clear his name.

I love this essay, Aaron. Here are some of my favorite lines: “Divinity is everywhere,” he says. “Think of what a disrespectful gesture you’re making to the divinity directly behind you.” AND No thing is pure and deserving of worship. No thing is inherently taboo. AND "Empathy with other animals is a window, one through which we can catch tantalizing and enlightening glimpses into a universe we can’t fully apprehend."

I wonder if you ever read Alexandra Horowitz's Inside of a Dog--in which she talks a lot about a dog's Umwelt. https://www.nytimes.com/2009/09/09/books/excerpt-inside-of-a-dog.html

I know that thinking about my dog's umwelt helps me to think about my own, and other people's and if we all did this, I believe the world would be a less divided place. Thanks for this post!