We like other colors

But pink just looks so good on us.

P! Panic!

I! I’m scared.

N! Nauseous.

K! Death!— The Barbie Movie (2023)

When I'm not writing the exact way I write in this space, I tend to write pretty slowly. I pick a specific structure and a tone, and then figure out step by step what to write to meet those constraints. I can write quickly, here, for now, because I'm shifting tone ad-hoc, and typically figuring out the structure as I write and edit. One downside is the existential nausea of freedom. I feel like I'm defining myself with my choices, and no part of feeling like a woke anarchist war-nerd carrot truther sits comfortably.

The prolific Edgar Allan Poe claimed sometimes, as in “The Philosophy of Composition,” to be the structure-first kind of writer. He’d pick a form and a desired effect, then proceed methodically. Critics are skeptical. I do think he tried, often, to lock most of his self out of his writing choices. Poe was depressive, perpetually grieving, messy. He might've liked it if his writing could take him away from that. But wherever you go, there you are.

While Poe always tried to be as original as possible, Shakespeare almost always took his plots from someone else. He kept enough of his self out of his words to fuel centuries of theories that the actor named Shakespeare was a front for a different writer. Sure, he wrote a play called "Hamlet" a few years after losing his only son Hamnet. But "Hamlet" is the prince's name in the original legend. He might have told himself it was just a coincidence. Maybe Shakespeare was the original denier of his own authorship.

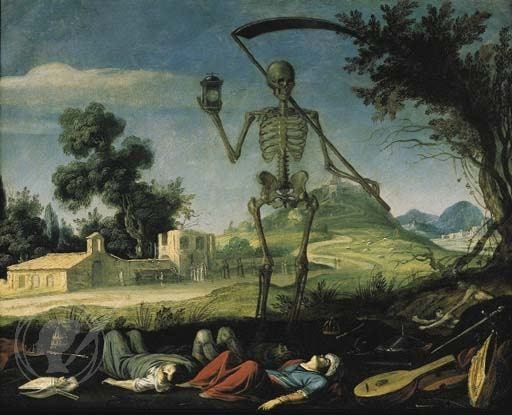

Prospero Accidentally Conjures Death

The Tempest is one of very few Shakespeare plays to not be a direct adaptation of anything. This is exciting, because it means people can read it as autobiographical, with the sorcerer Prospero as Shakespeare’s author avatar. Which is easy to do—Prospero literally writes a play within the play.

Prospero’s power comes from spirits he has bound to his will, chiefly Ariel and Caliban. Ariel is loyal, if a little needy. Caliban is constantly plotting to make mischief and escape. In Act 4, Prospero commands Ariel to whip up a quick production of his play about the sanctity of marriage, which he’s increasingly concerned his daughter needs to see like right now. It’s all going well. Prospero has to hush the praise from his tiny audience, because too much talking will literally break the spell. But then, we get to a scene-within-the-scene where farmers are celebrating a wedding, some of them fresh from the harvest.

You sunburned sicklemen, of August weary,

Come hither from the furrow and be merry.

Make holiday: your rye-straw hats put on,

And these fresh nymphs encounter every one

In country footing.

Enter certain Reapers, properly habited.

As the spirits-as-reapers dance, presumably carrying their sickles or stowing them nearby, the watching Prospero has a sudden realization.

I had forgot that foul conspiracy

Of the beast Caliban and his confederates

Against my life: the minute of their plot

Is almost come.

He decides he has to end the play early to deal with the little matter of his own imminent murder. The thespian spirits vanish with, in the (real) stage directions, “a strange, hollow, and confused noise.”

Ariel understood the assignment. One of the three gods in the play is Ceres, goddess of the harvest (whence, cereal). Plays with weddings are supposed to have celebrations near the end. So it’s only logical to have people carrying harvesting implements doing a merry dance. Is it really Ariel’s fault that a spirit grinning and holding a scythe has some other connotations?

The reaper as metaphor for death is ancient, and well-known in Shakespeare’s time. The adjective “grim,” though, didn’t become part of the Grim Reaper until much later. One of the earliest attestations is in a magazine edited by Poe. In Shakespeare’s time, skulls grinned in memento mori art, and so, often, skeletal reapers did too. And hey, sometimes they danced.

Shakespeare’s own sonnets, in fact, use the sickle image for mortality. Such as 116, which exemplifies the common tendency to start out talking about eternal love and then remember the inevitability of death. Oh, and has the word “tempests” in it.

Let me not to the marriage of true minds

Admit impediments; love is not love

Which alters when it alteration finds,

Or bends with the remover to remove.

O no, it is an ever-fixèd mark

That looks on tempests and is never shaken;

It is the star to every wand'ring bark

Whose worth's unknown, although his height be taken.

Love's not time's fool, though rosy lips and cheeks

Within his bending sickle's compass come.

Love alters not with his brief hours and weeks,

But bears it out even to the edge of doom:If this be error and upon me proved,

I never writ, nor no man ever loved.

Prospero had tried to write some light, wholesome entertainment, but Death personified had snuck in anyway. Now all of his troubles have returned to the forefront of his mind.

The genre-defining 1956 film Forbidden Planet, a loose adaptation of The Tempest, uses science fiction to literalize the metaphor here. The Prospero-analog, played by the excellently-named Walter Pidgeon, is using alien technology, which he doesn’t fully understand, to shape his planet to his will. Just think about what you want, and the machine will make it so. Or so he believes. But actually, the machine responds to all of his thoughts, including his unconscious ones. The “alien monster” menacing him, the Caliban analog, was unwittingly created by him. It’s “a monster from the id,” realizes young Leslie Nielsen.

If Prospero is Shakespeare, Caliban is Shakespeare’s poorly suppressed morbid thoughts, his grief for his son and for others. He tried to write straight adaptations of old stories, but somehow everybody kept dying. King Lear, for example, has a happy ending in the source material. Cordelia gets her dad back in power, and later inherits his throne. Audiences familiar with the original story, or even another recent English play adaptation, were in for a rude shock when Lear staggered on stage in the fifth act, carrying his daughter’s body.

The Tempest is a triumphant farewell, but it’s also kind of an apology for the mess his unruly spirits have made. From the epilogue:

Gentle breath of yours my sails

Must fill, or else my project fails,

Which was to please. Now I want

Spirits to enforce, art to enchant,

And my ending is despair,

Unless I be relieved by prayer,

Which pierces so that it assaults

Mercy itself and frees all faults.

As you from crimes would pardon'd be,

Let your indulgence set me free.

Prospero Accidentally Conjures The Pandemic

People writing about the play-within-a-play in The Tempest usually refer to it as a “masque.” The word isn’t used in the play, and nobody’s described as wearing masks, but the tone of it is similar to some light entertainment, featuring gods and masks, that the Elizabethans did use that word for. We can be pretty confident that Poe was thinking of it like that when he wrote the story of his own Prospero, The Masque of the Red Death.

The dancing reapers wouldn’t have been skeletons. They’re “sunburned sicklemen.” Red deaths in a masque. I am elated to not be able to find anybody else pointing this out in Google Search, Books, or Scholar.

In Poe’s Masque, which never directly alludes to The Tempest, a prince named Prospero has isolated himself—but not because he was deposed like his namesake. It’s for the same reason we were isolating ourselves recently. There’s a deadly pandemic, one that is asymptomatic until half an hour before you die, when you start bleeding profusely. People call it the “Red Death.” So Prospero, with a thousand of his closest friends, retreats to a “castellated abbey” of his own design, provisioned with all the creature comforts.

There were buffoons, there were improvisatori, there were ballêt-dancers, there were musicians, there were cards, there was Beauty, there was wine. All these and security were within. Without was the “Red Death.”

After “the fifth or sixth month of his seclusion” (time is hard to measure in these situations), the Prince decides to throw a masquerade ball. (If you ever suspect you are in a story, do not throw a masquerade ball.) The text, which is pretty short, spends a lot of its words describing the decor. The ball is held in a suite of seven connected rooms he’s decorated according to a different color theme. From east to west, the rooms are blue, purple, green, orange, white, violet, and black. Each is lit by natural light through a stained glass window of the appropriate color—except the black room, where the window is red.

Most of Prospero’s pod refuses to go into that room. It’s all in black, lit by “blood-red” natural light from the outside. It seems to symbolize the very thing they’re hiding from.

Why did Prospero make it like that? It probably seemed to him like he was just following inexorable logic. In my head, it goes like this:

He wanted to do a suite with color themes. Sure. Seven is the appropriate number for colors, of course—that’s why Newton made his controversial decision to include “indigo” in the spectrum. Newton drew correspondences between his seven colors and the seven notes in an octave (the word octave, from the Latin for eight, is an annoying example of a fencepost error sneaking into language). Also the seven visible heavenly bodies, from there to the seven days of the week, and so on. So Prospero needed seven colors for his scheme. He can’t just do Newton’s ROY G BIV because he doesn’t want a red room under the circumstances, and light coming in through yellow stained glass just looks like sunlight. Also, come on. Indigo’s just dark blue. Who are you trying to kid, Isaac?

He needs three new colors to replace the three rejects. Okay, black and white are classics for a reason, they’re obvious adds. And for the last, ugh. Well, violet is technically different from purple, right? He’ll just put them as far away from each other as he can without having either one on an end.

But now there’s the problem of the light in the black room. A black stained-glass window wouldn’t really be a window. (Our story takes place before the invention of the blacklight, and incidentally also probably before the 1597 invention of the hallway, judging by the layout description.) He can’t use any of the colors from the other rooms, because that’s not the vision. So, oh well. Guess there has to be a little red.

In some unexplained mystical way, this “forced” inclusion of a red room allows the Red Death to finally enter their sanctuary and kill them all. Personified as an intangible spirit wearing a blood-spattered costume, the Red Death is finally unmasked in that fatal seventh chamber, claiming the Prince as its first bloody victim. “He had come like a thief in the night,” Poe writes, alluding to Thessalonians 5:

But of the times and the seasons, brethren, ye have no need that I write unto you. For yourselves know perfectly that the day of the Lord so cometh as a thief in the night. For when they shall say, Peace and safety; then sudden destruction cometh upon them, as travail upon a woman with child; and they shall not escape.

Both Prosperos, like the authors they stand in for, have their pleasant creation rudely interrupted by death—a death that seems at once of Ariel, an obedient consequence of following a plan to its logical conclusion, and of Caliban, Prospero’s own intrusive thoughts of death making their mischief.

In Summary

“Stop complaining about how dark we are,” cry Shakespeare and Poe. “It’s not our/Prospero’s fault. If art is holding a mirror up to nature, and nature is red in tooth and claw, then, well, Ariel’s just doing the needful. If art reflects the artist, then Caliban, that imp of the perverse within us all, will always sneak out of the recesses of the soul and onto the page.”

Maybe. But even in blaming their subconscious minds, they’re passing the buck a bit more than I think is strictly honest. Death sells. Shakespeare was competing with bloodsports like bear-baiting next door. Poe believed, probably because it was true for him, that sadness was the most intense of all emotions, and therefore the best at drawing readers in. Death comes in through the intrusion of the id, and the logic of the ego. But it also gets motivated by the superego, popping up to remind the writer that death will get them money, and money can be exchanged for goods and services.

Goodnight, Barbies! Don’t forget to subscribe!

Bonus: The 108 Lines of The Raven

In “The Philosophy of Composition,” Poe gives a (possibly a little tongue-in-cheek) account of how he wrote The Raven with “the precision and rigid consequence of a mathematical problem.” He knew it needed to be about 100 lines, he says—long enough to make room for lots of repetition, while short enough to achieve a “unity of impression.” He ended up with 108.

One hundred and eight is a significant number in many Dharmic religions. In Hinduism, among others, strings of 108 beads are used in prayer. Buddhists have lots of lists of 108 things. There are varying accounts of why 108 is so important, most of which have to do with multiplication and combinatorics. 108 is 2² * 3³, what you get when you start with 1, double it twice, and triple it three times. Some Jains say there are 108 sources of bad karma: four possible underlying emotions (anger, pride, conceit, greed), each of which can be expressed in three ways (thought, speech, action), with three temporal stages (planning, preparing, starting) and three relationships to the act (doing it yourself, making someone else do it, supporting someone else in doing it). There’s a different, Buddhist, factorization too: the 108 feelings consist of six senses, each of which can be painful, pleasant or neutral, internally or externally motivated, and remembered, happening now, or anticipated.

It’s likely the original motivation was more abstract. The use of strings of beads to do arithmetic, as in an abacus, is older than all of these explanations. Numbers whose only prime factors are small, known as “smooth numbers,” are useful because they can be divided evenly in many different ways. We use 60 minutes in an hour and 360 degrees in a circle because both numbers are 5-smooth, and we use 24 hours in a day because it’s 3-smooth, like 108 is. So probably these prayer strings started out as pocket calculators, with the number chosen for practical ease of use.

Poe might have known about this symbolism. There were plenty of English-language books talking about it in his time, but his writings about the Exotic East don’t inspire much confidence in his knowledge of dharmic numerology. I’d take 2:1 odds he didn’t know.

But that doesn’t mean it’s entirely a coincidence, either! The Raven consists of 18 stanzas of 6 lines each. The six line stanzas let Poe use an unusual rhyme scheme: ABCBBB. Each stanza starts out with no rhyming, and then collapses into oppressive repetition of the middle line’s rhyme, which is always the same (“or”). 6 is the smallest possible length for which this works. ABBBB or ABCCC wouldn’t give the desired effect of having the monotonous second half pluck out part of the seemingly free first half. BABBB would cause the first B to seem like it’s part of the previous stanza, since it’s the same B every time. ABAA has the same problem, and so on. Ergo, 6 lines per stanza.

The story of the poem has three sections, each 6 stanzas long. In the first, the narrator is alone, feeling sad and anxious. In the second, a raven comes in and cheers him up. In the third, it occurs to the narrator, with increasing force, that the raven actually symbolizes his eternal grief, sending him even deeper into melancholy than before the bird showed up.

Each six-stanza section copies the structure of the individual stanzas, in action rather than rhyme—three stanzas where it feels like the story is progressing, and then three that are ominously or oppressively repetitive. In the first section, the narrator feels a dull lack of interest in the knocking on his door (1), ignores it entirely to focus on his grief (2), then starts feeling scared (3), asks who it is and looks outside (4), asks who it is and looks outside (5), then wonders who it is and looks outside (6).

So the structure of the poem’s composition gives rise to another 108, in a similar way. 3 sections of 6 stanzas of 6 lines, where each 6 is a 3*2.

The factorizations in each case are a little different. The Jain one is 4*3*3*3, the Buddhist one 6*3*2*3, and Poe’s 3*6*6, or more precisely 3*(3*2)*(3*2). Multiplication comes out the same no matter what order you do it in, so as long as you’ve got two factors of two and three factors of three in there somewhere, in any order, you’ll get 108.

This tickles me. Plenty of pop art has 108 hidden in it as an easter egg, and/or as an allusion to various religious concepts. But in setting out to invent a new poetic form from first principles, Poe ended up in deeper alignment with the long-lost originators of the number’s usage. 108 is the number of steps to nirvana, the eternal annihilation of the soul. 108 is the number of lines you need to convey that Lenore is never, ever coming back. And the reason, in both cases, is the same arithmetic. Ariel, the spirit of death-as-rigid-consequence-of-structure, strikes again.

Or, to return to a less recent topic, we could say that spirituality, art, and mathematics have all converged here in a single pure expression: a game played with glass beads.

I feel like now I have to write something that is either 108 words, 108 lines, or 108 pages. But first I kind of want to buy those beads....