Yesterday, I was recommended Kathryn Schulz's "The Secrets of Suspense" and, thanks, Benjamin. It’s a great piece, well-written and interesting. I think anybody who’s been reading this blog will probably agree. It’s in the May 27th issue of the New Yorker.

Okay. Everybody either read it, bookmarked it, or opened it in a new tab? Good. Now I’m going to harp endlessly on an extremely minor factual error in the piece.

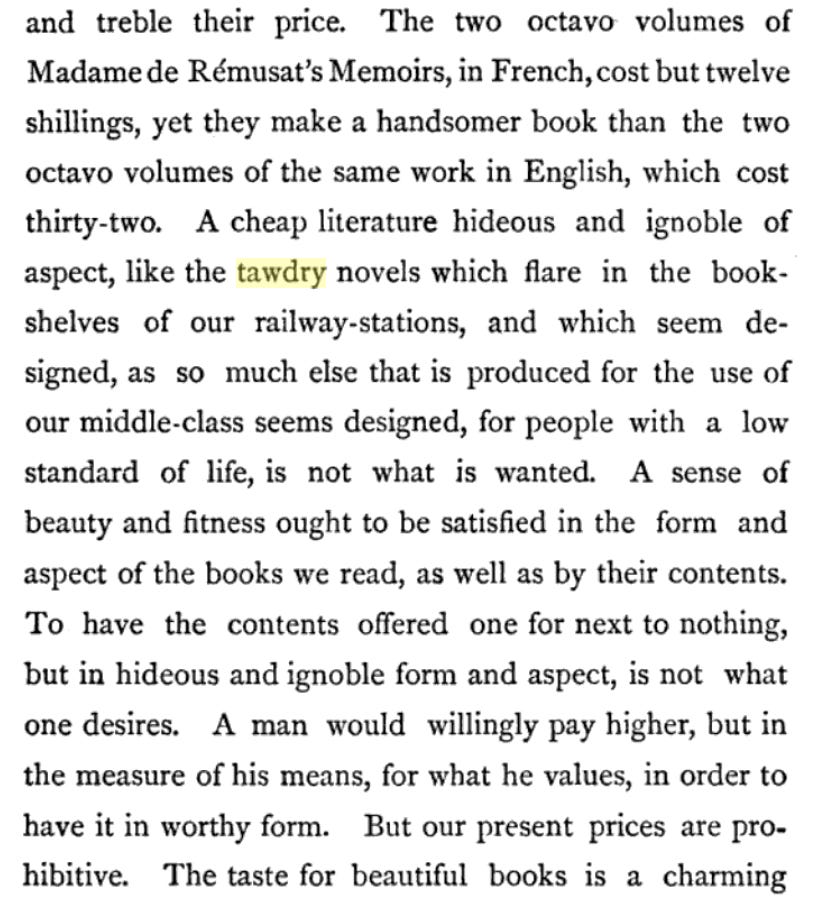

“Tawdry,” “hideous,” “ignoble”: thus did Matthew Arnold denounce so-called railway books, the potboiling precursors to airport fiction.

This line caught my curiosity, because I hadn’t heard the phrase “railway books” before, and it’d be interesting to see whether I could trace their ancestry back to the pre-railroad book I’ve referred to as the original page-turner. I went looking for 19th-century references to “railway books,” was puzzled that I couldn’t find any that weren’t talking about books about railways, and decided I needed to go to the source. (Turns out, the 19th-century term was “railway fiction,” and it did indeed mean what we mean by airport fiction. So that’s cool.)

Matthew Arnold, though, doesn’t use the term “railway fiction” in the essay those adjectives come from. Because he’s not talking about the genre. He’s not talking about the content of the books at all.

Arbitrary Section Break To Build Suspense

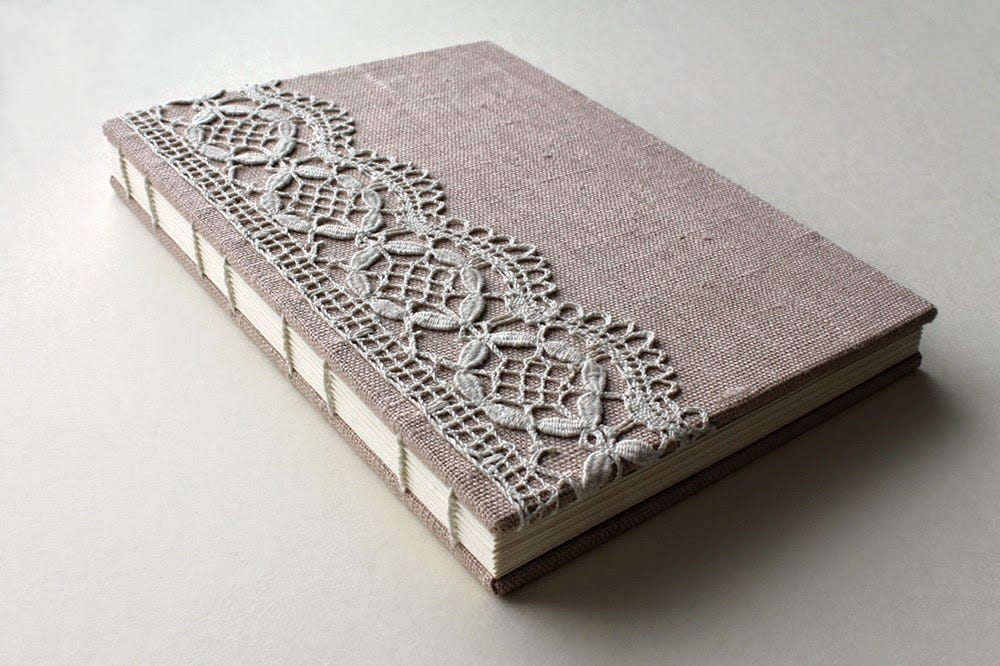

In his 1891 essay, poet and critic Matthew Arnold complains about the aesthetics of books you see on sale at a railway station. Here’s the paragraph, via Google Books:

Arnold is talking about a gap in the prices of books. You could buy “penny dreadfuls,” serial fiction that cost a penny per installment, or “yellow-backs,” the non-serialized counterpart, for a few pennies a book. Or you could spend money most people didn’t have, and get a beautifully bound volume to show everyone how rich and intellectual you were. Arnold disliked the first because the publication process cut every possible corner in order to sell books that cheaply, and the result was gross-looking. He disliked the second because it locked most people out. “Cheap books,” he says, are what is needed. Ideally, three shillings a pop.

This misreading isn’t original to Schulz, who almost certainly was working off someone else’s inaccurate summary of the essay that used the phrase out of context. People seem to have delighted in misrepresenting Arnold as more elitist than he actually was. This shenanigan was made possible by shifts in the meanings of the words “tawdry” and “ignoble.” Today they’re mainly used to convey moral judgments, but that wasn’t the dominant sense back then. “Tawdry” was an aesthetic judgment, and “ignoble” a class one. Paired, they mean “gaudy and cheap-looking,” not “the sign of a rotted soul.”

“Tawdry” has a delightfully weird etymology. It’s a contraction of the phrase “Saint Audrey lace.” Saint Audrey, who died of a neck tumor as punishment for having worn necklaces, was commemorated with an annual fair at which you could buy cheap lace, designed to let women hide their bodies while still looking a little fancy. In Shakespeare’s A Winter’s Tale, the comical commoners talk about buying “a tawdry-lace and a pair of sweet gloves.”

It started out neutral—tawdry lace was a pretty thing you could get at an affordable price. But words meant to denote something lower-class almost always follow the same lifecycle. First they turn into slurs. Then they come to mean “immoral.”

“Villain” used to mean “villager.” “Knave” used to mean “male servant.” “Ignoble” meant “not a member of the titled nobility.”

Hence, “tawdry.” Supposedly, people stopped naming their daughters Audrey for a few generations, until the association broke.

Wiktionary’s earliest example sentence using “tawdry” in the sense of “immoral” is telling.

[T]he "greaser" was a dirty, idle, shiftless, treacherous, tawdry vagabond, dwelling in a disgracefully primitive house, and backward in every aspect of civilization. — Stewart Edward White, chapter 1, in The Forty-Niners. 1918.

This sentence explicitly conflates “poor” and “untrustworthy” (probably this was satire, I haven’t checked). The string of epithets do something similar, implicitly. “Dirty”/”Clean” is both a class marker and a moral judgment. “Idle” and “shiftless” both derive from words meaning “lacking in something”—they came to mean specifically lacking in work ethic or executive function, but were once general enough to apply to poverty as well. “Vagabond,” of course, means “homeless.” Of all the epithets, only “treacherous” doesn’t derive in some way from a reference to poverty. You have to go pretty far back in treacherous’s etymology before you get to anything different, and even then, the only difference is that the connotations are more like the modern “hack” or “trick”—the Latin tricor usually refers to deception, but also could be used to describe harmless shortcuts.

These shifts are examples of a euphemism treadmill. When a word turns into a slur, we replace it with a new, neutral word—which then, eventually, turns into another slur. You have to keep coining new words just to stay in the same place.

Printed Lies

Judging a book by its cover also connects to a similar linguistic evolution pattern. Words for cheap methods of publishing end up taking on connotations of dishonesty.

“Libel” used to mean “pamphlet.”

“Tabloid” used to be a neutral term for a newspaper that was physically smaller than a “broadsheet,” a word that now means “newspaper with high quality journalism.” See also words like “rag.”

“I read a tweet that said…” is less credible than “I read a post that said…”, which is less credible than “I read an article that said…” and so on.

One way to think of this phenomenon is as a consequence of r/K selection. In r-selection, you try to maximize your rate of production. In K-selection, you instead try to maximize the capacity (German Kapazität) of everything you produce to survive. r-selection, or r-strategy, is quantity over quality, while K-strategy is the reverse.

Both of these strategies appear in biological reproduction, with which these terms are most associated. They’re probably the origin of male and female—sperm are basically low quality, mass-produced eggs. And the same dynamics are at play with publishing, where you’re spreading your memes instead of spreading your genes. Research and fact-checking are time-consuming and expensive, so they only make sense in a K-strategy. Lies, or um, outlandish claims made without citing sources, can be written more quickly—as Jonathan Swift wrote, “Falsehood flies, and the Truth comes limping after it.” (A misquoted version of this, involving boots, is far more popular, proving the point.) And if you’re publishing something with factual errors, it probably won’t have a long shelf-life anyway, so might as well publish it as cheaply as possible. Hence the r-strategy, aka spam. It often evolves under dangerous conditions.

Arnold cared about the aesthetics of books because of a common intuition—different kinds of “quality” are correlated. In this case, truth and beauty. That intuition comes from this r/K selection dynamic, which you can see in many domains.

It’s a good heuristic, but be careful. “Quality” can be a slippery concept. Sometimes what counts as high-quality from the publisher’s perspective can mean low-quality to the reader. A benign example is if you see two contradictory signs next to each other, say a glossy, multicolor print sign reading “Business hours 9:00 AM to 5:00 PM weekdays” and a piece of paper with “Open 8-9 AM MWF” written on it in magic marker. Here we all intuitively understand that the second one is probably more accurate. When there are two different signs, it means one describes the normal system and the other describes a current exception to it. The one describing the normal system is expected to have a longer life, so it’s made with a higher production value, but its truth value is lower.

In other cases, this mismatch can derive from a values difference. “Don’t read the New York Times, that’s written by the Man. Check out my zine!” Higher production value means higher budget means beholden to an elite interest. It’s an awkward situation—we’d like to have high quality media from diverse perspectives, but those concepts belong to different strategies. Fixing this is the main purpose of tenure—give someone money to do K-selection without thereby gaining leverage over them. Crowdfunding is another traditional solution.

Social media has given us a new way to be suspicious of high quality. Increasingly, if something goes viral, it means it was designed to go viral, which gets more and more decoupled from truth and beauty as people get better and better at creating bait. Snapchat’s signature feature is that messages, by default, self-destruct after reading. This was originally done for privacy and thrift, but now Snapchat advertises it as “the antidote to social media.” When messages are inherently perishable, users are incentivized toward r-strategies, which makes it less profitable to be evil. Maybe.

Generative AI is currently breaking all of these rules. It’s getting cheaper and cheaper to create media with what used to be the markers of high quality. Used to be, if a bunch of different people all posted different photos of the same thing, you’d be confident they weren’t doctored, because doctoring a photo takes time.

K-strategy media is proof of work

The “proof-of-work” concept that underlies bitcoin is a synthesis of the r/K selection model from biologist E.O. Wilson and the Byzantine Generals problem from computer scientist Robert Shostak. (Both of them had coauthors and antecedents, but I’m not stopping to look them up because I write these posts quickly.) In the Byzantine Generals problem, originally conceived as a metaphor for fault tolerance in distributed systems, we imagine generals from the Byzantine (Eastern Roman) Empire trying to coordinate with each other while all communication channels are being flooded with lies. Shostak picked the name because the solutions tend to be as elaborate as Byzantine architecture, and because nobody identifies as Byzantine so it doesn’t feel offensive.

Outside of computers, one solution to the Byzantine Generals problem could involve expressing all messages in the form of sonnets, with the key details incorporated into the rhyme scheme so that they’re harder to tweak. By making composing messages time-consuming, you ensure that as long as the majority of people sending them are honest, the majority of valid messages are honest, so then you can just do a majority vote.

Inside of a computer, sonnets aren’t particularly easy to compose or check, so bitcoin instead uses a hashing function—a way of reducing any message to a single large number, in such a way that any changes to the message, no matter how small, tend to result in large changes to the number in unpredictable ways. Messages about bitcoin transactions are required to hash to a relatively small number, which requires a lot of trial and error.

A lot of human culture, as well as the mating rituals of other animals, uses proof of work. To the extent that the r/K model applies, Byzantine architecture implies sturdy workmanship, elaborately-crafted art implies artistic merit, elegantly-stated theories imply scientific insight, ornate fences are probably harder to get through, expensive or thoughtful presents prove your lover isn’t playing the field, dressing presentably implies behaving respectably, and so on. It’s no coincidence that males, the sex derived from r-selection, tend to have to do more work during courtship.

This dynamic leads to there being more beauty in the world, but it’s also quite wasteful. As we’ve seen, another downside is that it leads to an association between poverty and treachery. If your lover buys you a cheap present, is he insincere or just poorer than you thought?

Ethereum, another cryptocurrency, recently migrated from proof-of-work to proof-of-stake, mainly out of concern for environmental impact. In proof-of-stake, you demonstrate that being caught in a lie would be costly for the author directly. In human discourse, this is the function of having a reputation for truthfulness. Whenever the New York Times prints an outright lie, or makes a serious factual error, its core business model is damaged. Too many of those would kill the paper. Tabloids, conversely, don’t tend to lose much business when they get something wrong. So if an article is provably published in the New York Times, it’s proof that someone staked a lot on its authenticity.

As work becomes easier and easier to fake, and we all get more and more punk, proof-of-work becomes less effective. Reputation, filling the gap, gets more valuable. Substack is filling a niche analogous to Arnold’s three-shilling book. If this article were full of lies and/or simple errors, I’d be risking my investment of time into writing this newsletter, so you can be medium-confident that I’m being mostly accurate. (The article that pointed me to the Winter’s Tale quote above misattributed it to Twelfth Night. I’m looking out for you.) I don’t have enough at stake for you to be highly confident in my accuracy, though. In exchange, you get the benefit of diversity—my voice is probably a little too weird for The New Yorker, and they have limited space, but through Substack you get to read me anyway.

Matthew Arnold wanted publishing to be popular and accessible, without being tawdry. The internet opens up a lot of potential solutions, but I don’t know if I’d say we’ve quite cracked it yet.

Bonus: Strategies For Encouraging K-strategies

Matthew Arnold’s essay was about Copyright. At the time, the United States didn’t have any copyright laws, due (Arnold thought, I think basically accurately) to our ideological commitment to free speech. Because this made it harder to make a profit from publishing high-quality books, it skewed the English-speaking publishing world towards lower-quality ones, and raised the price, because the revenue needed to come from a smaller share of the readership. The result, as he noted, was that the same book published in French was both less expensive and prettier. International copyright agreements would, and did, help fix that.

When I went touristing around Europe for a couple of weeks recently, I noticed a different disparity in writing quality: the graffiti was more interesting to read. People wrote in complete sentences, with punctuation, about stuff they actually cared about. In France it was mostly about climate change. In Amsterdam, I saw a haunting little poem that’s stuck with me, and that I haven’t been able to find online, painted I think on the plywood barrier to a construction site.

Before the war, we danced.

After the war, we danced.

And during the war, some of us kept on dancing.

In most of New York City, you don’t get much graffiti like this. It’s usually just an artist’s signature, or symbol, or maybe a three-word slogan. After that there’s a quality gap, and then you get giant elaborate street art murals. The difference, I think, is that New York City has historically had a policy of aggressively removing graffiti, starting with Mayor Giuliani. The city spends millions doing it, although I think they’ve ramped that down since 2020. The result is that the median survival time for graffiti is smaller than in Avignon or Amsterdam, so the incentives shift toward r-strategy in NYC. Even when the incentives change, culture is sticky, so it’d probably take a long period of graffiti tolerance before it started to improve in NYC, or a long period of intolerance for it to start to degrade somewhere else.

Protecting artists from theft and censorship gets us more art in the intersection of accessible and good. That’s one reason for a paradoxical effect where curated collections are often lower-quality than non-curated ones. If your work might get arbitrarily rejected, you’re less incentivized to put in effort.

Or you can just decide you don’t care if your work lasts. I don’t know if it survived Covid, but the pedestrian walkway on the Manhattan Bridge had a culture of great graffiti as late as 2019. It got erased all the time, but transient art can be good art too.

You might (or might not) be surprised to hear that producing inexpensive books for the masses has an Emma Goldman connection. Her great nephew Ian Ballantine grew up to create paperback books that people could afford. Starting with Penguin and then with the eponymous Ballantine books. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ian_Ballantine His mother, Stella, was Emma's right hand person for much of her life, starting when Stella was a little girl and declared that when she grew up she would help Aunt Emma, which indeed she did! And clearly Emma's ideals passed directly to Ian... I have a good quote from him in the book. (At least so far I have it!)