Meet William Godwin, the 18th-century philosopher who was right about everything

Except how to parent daughters, and whether stars are real.

William Godwin’s legacy has been completely overshadowed by his wife’s and their daughter’s. If you traveled back in time 250 years and told him that, he’d be thrilled. One of his first big pieces of political writing was a biography of his late wife, Memoirs of the Author of A Vindication of the Rights of Woman, a work so fiercely feminist that he was forced into semi-hiding for decades by the backlash. He pushed his daughter, then also named Mary Wollstonecraft, into writing, and was excited about her potential. So no complaints from him, I think, that he’s mainly known for his connection to feminism and Frankenstein. But I’ve been reading his own work lately, and wow. He should get a little love too.

Part 1: “The very zenith of a sultry and unwholesome popularity”

Godwin mainly wrote about political and moral philosophy, but his fiction was shockingly influential. It’s not too much of an exaggeration to say he invented the page-turner. Godwin had the idea to promote his political views (we’d call him an anarchist, liberal, or libertarian) by writing a gripping novel about a falsely-accused hero battling corrupt institutions and oligarchs. He was slow and methodical about it, first constructing a full outline meant to avoid any dull plot points, and then only writing when he felt like it in order to avoid any dull prose. This worked brilliantly. The Adventures of Caleb Williams tore through the English-speaking world. People read it in one sitting, and this is a book that would probably be published as a trilogy today. Nobody had antibodies against tactics like ending a chapter with “They therefore contented themselves with stripping me of my coat and waistcoat, and rolling me into a dry ditch. They then left me totally regardless of my distressed condition, and the plentiful effusion of blood, which streamed from my wound.” Sure, it’s 3 AM and candles are expensive, but are you just going to leave Caleb bleeding out in a ditch?

This book, and Godwin’s description of his writing process, helped create the next generation of popular writers — the first, I think, who could actually make a living off it. Charles Dickens and Edgar Allan Poe talked about it the way playwrights talk about Shakespeare. I’m going to take the liberty of translating Godwin’s explanation, from a preface to one of many reprints, into a more clickbait-friendly modern how-to form.

How To Write A Page-turner

Start with an outline, and write it backwards. Describe an exciting event, then brainstorm what needs to come before that to make it make sense.

Only write when the spirit moves you. If you lose a day, you lose a day. If you write something boring, you risk losing the whole project.

Your villain needs to be impressive enough to be scary, and cool enough to be engaging when made the focus of the story. It follows that the villain should be set up as a compelling, romantic figure, and their turn to evil be a great tragedy.

Allow yourself to think “this book will change the life of everyone who reads it” while you’re writing. You can’t write at your best if you’re too on guard against being conceited. If you need to, after it’s done you can decide that it’s terrible to make up for your earlier pride. But publish it anyway.

Write in the first person. You need to be inside the mind of the protagonist, not just watching what they do.

Be utterly shameless about reading and imitating other fiction you like. You’re a unique person and you’re going to write something unique no matter what.

One of those next generation writers inspired by Caleb Williams was Godwin’s daughter, who we know as Mary Shelley. She’s said to have read and reread the book many times while writing Frankenstein. Which is all the more interesting considering she and her dad weren’t speaking at the time. She’d run away from home. (How’s that for a chapter-ending cliffhanger?)

Part 2: Um, actually, William Godwin was the scientist. Mary Shelley was the monster.

In a sense, Mary Shelley never knew her mother and namesake, who died giving birth to her. But Godwin told her everything about her mother, and encouraged her to read everything she’d written. Mary grew up loving and admiring both of her parents, and was determined to follow their lead. Godwin, unfortunately, seems to have let politics get in the way of parenthood. His biography of Wollstonecraft confirmed that Mary’s elder sister was illegitimate, which ruined her life. He publicly advocated against marriage and for free love, while privately urging pragmatic conformity from Mary, to her frustration. When she eloped with Percy Bysshe Shelley, he cut her off completely. The way people often see it, Godwin felt that since gender was a social construct, there was no reason Mary had to be a woman, rather than a perfect, sexless demigod.

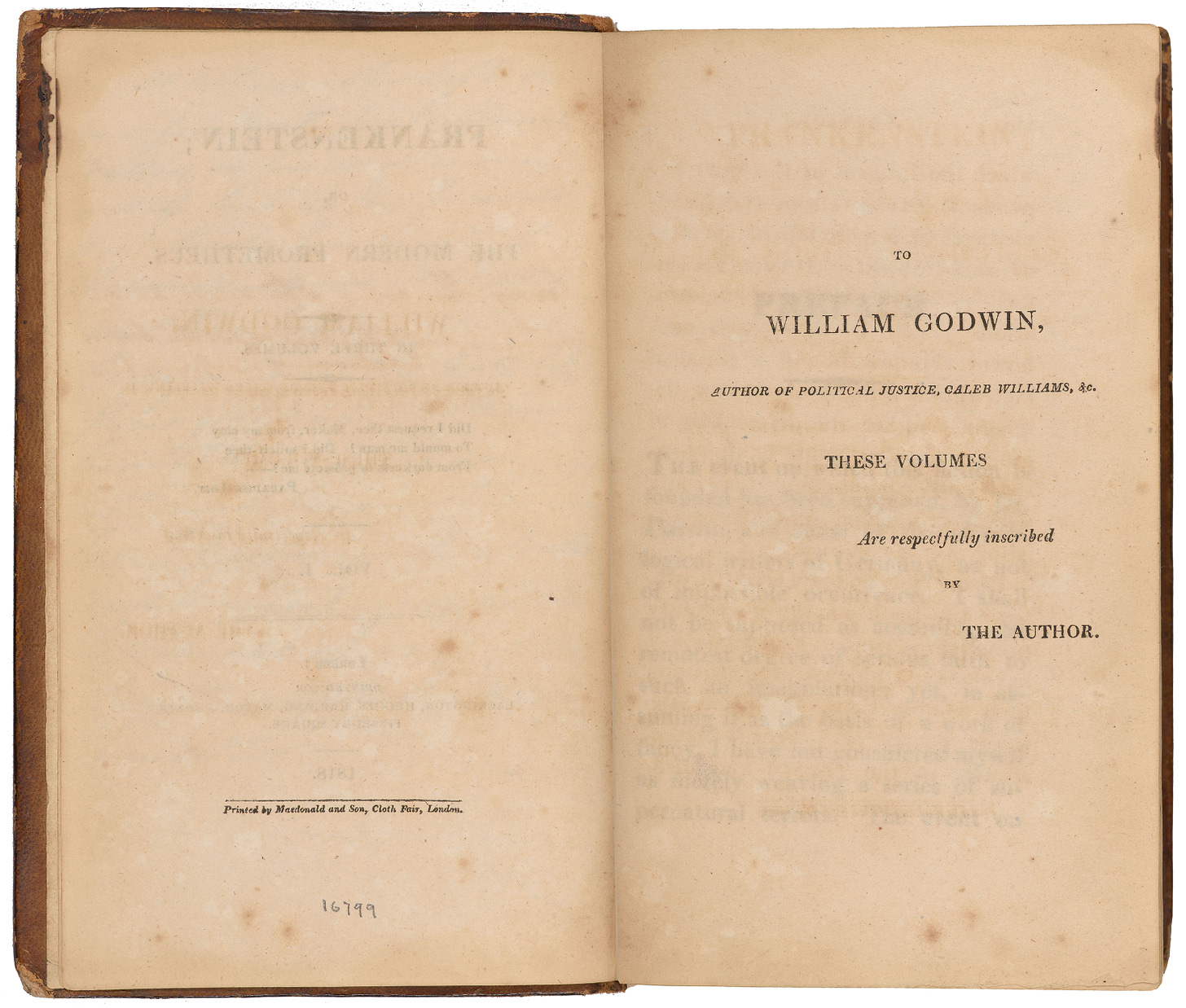

Mary started writing Frankenstein during this period of estrangement. It’s a story of a creator who rejects his creation, and it’s very easy to read it as an allegory about her father, as well as a criticism of his Enlightenment sensibilities. Although they eventually reconciled, it hasn’t been lost on critics that her fiction has a lot of terrible and/or absentee dads — a trope that’s become a staple of the genre. She dedicated Frankenstein to “William Godwin, author of Political Justice, Caleb Williams, etc.” Vicious.

Mary Shelley’s capacity, as Godwin predicted to a friend when she was younger, far exceeded that of her parents. Doctor Frankenstein is an undying figure in our cultural canon, while her parents’ characters are long gone. But Godwin himself has been immortalized as the mad scientist. So in a way, he’s now become her creation.

Part 3: Malthus’s “name should be preserved, whatever becomes of the volumes he has written.”

Here’s another questionable legacy of Godwin’s: the adjective “Malthusian.” Thomas Malthus’s 1798 Essay on the Principle of Population, written in response to Godwin’s nonfiction, argues that prosperity (when shared overly equally, anyway) leads to population increase, which then reduces per capita prosperity by spreading it out. This view polluted political philosophy for the next two hundred years, and, in accordance with Godwin’s wish, has survived in phrases like “Malthusian catastrophe.”

Malthus was wrong. Prosperity does lead to population increase, to a point. As Godwin pointed out in his riposte, prosperity also gives us the slack we need to find meaning in activities other than sex and parenting. He predicted, correctly, that population growth would eventually slow in developed countries, although he never realized how personally responsible he might’ve been—rates of sexual activity plummeted, probably forever, after Netflix started streaming entire seasons of TV shows, a watershed moment in culture that’s directly downstream from Caleb Williams.

That’s not the main reason Malthus was wrong, though. People started questioning his reasoning during the Industrial Revolution, as it became clear that there’s no particular reason overall prosperity can’t grow faster than population. Then, Norman Borlaug’s Green Revolution in the 20th century was a decapitation blow to mass famine, the main horseman in Malthus’s prophesied apocalypse. The key insight feels very simple now, but is still missed by many: people, on average, create more than they consume. More people, therefore, means more prosperity per capita, not less, in the long run. (See also: immigration.)

It’s kind of amazing that Godwin was able to remain such an optimist after this experience. His attempts to improve the lot of the poor had an over-the-top terrible consequence—inspiring a writer to persuade far too many that the poor should, as Godwin’s disciple put in the mouth of Ebenezer Scrooge, “die and reduce the surplus population.” But he did remain an optimist. One of his last books, Thoughts on Man, is a beautiful love letter to humanity, civilization, and progress.

Part 4: (Or just go read Thoughts on Man, I don’t mind)

Thoughts on Man, published only five years before his death at age 80, doesn’t have as much historical significance as some of his earlier works. I’m going to talk about it a lot anyway because it made me really happy to read. It’s a loosely-ordered collection of twenty-three essays, united by an evangelical mission explained in the preface:

I know many men who are misanthropes, and profess to look down with disdain on their species. My creed is of an opposite character. All that we observe that is best and most excellent in the intellectual world, is man: and it is easy to perceive in many cases, that the believer in mysteries does little more, than dress up his deity in the choicest of human attributes and qualifications. I have lived among, and I feel an ardent interest in and love for, my brethren of mankind. This sentiment, which I regard with complacency in my own breast, I would gladly cherish in others. In such a cause I am well pleased to enrol myself a missionary.

He defends Man on many fronts, rebutting claims ranging from “most people are worthless” to “our lifespan is too short for our lives to have meaning.” He gets a lot of things right that people still get wrong today. And he gets one thing really hilariously wrong, which I’ll get to.

First, I want to share some of my favorite bits. He starts out talking about education.

I am inclined to believe, that, putting idiots and extraordinary cases out of the question, every human creature is endowed with talents, which, if rightly directed, would shew him to be apt, adroit, intelligent and acute, in the walk for which his organisation especially fitted him.

But the practices and modes of civilised life prompt us to take the inexhaustible varieties of man, as he is given into our guardianship by the bountiful hand of nature, and train him in one uniform exercise, as the raw recruit is treated when he is brought under the direction of his drill-serjeant.

The son of the nobleman, of the country-gentleman, and of those parents who from vanity or whatever other motive are desirous that their offspring should be devoted to some liberal profession, is in nearly all instances sent to the grammar-school. It is in this scene principally, that the judgment is formed that not above one boy in a hundred possesses an acute understanding, or will be able to strike into a path of intellect that shall be truly his own.

I do not object to this destination, if temperately pursued. It is fit that as many children as possible should have their chance of figuring in future life in what are called the higher departments of intellect. A certain familiar acquaintance with language and the shades of language as a lesson, will be beneficial to all. The youth who has expended only six months in acquiring the rudiments of the Latin tongue, will probably be more or less the better for it in all his future life.

…

But this method, indiscriminately pursued as it is now, is productive of the worst consequences. … [T]he very moment that it can be ascertained, that the pupil is not at home in the study of the learned languages, and is unlikely to make an adequate progress, at that moment he should be taken from it.

The most palpable deficiency that is to be found in relation to the education of children, is a sound judgment to be formed as to the vocation or employment in which each is most fitted to excel.

In other words—it’s not that 99% of people are talentless, it’s that we give everybody the same standardized education that is only appropriate for 1% of them, and then when most children fail, we blame it on them and they blame it on themselves. We too often make children’s lives about whatever they’re worst at, not what they’re best at. I tutored a neighbor kid for a few years when I was growing up. I thought it was my job to say “no, we can’t pretend to be characters from Powerpuff Girls cartoons right now, you need to learn math.” That was wrong. For a fraction of the cost taxpayers paid to traumatize him to the point that he would start chanting to drown me out when I said the word algebra, society could’ve given him three free meetings with an accountant per year and a lifetime supply of cheap solar-powered calculators. He didn’t need to learn math—he needed to learn what he was good at. He should’ve grown up being told to be a voice actor, not being told he was stupid.

As Godwin wrote (and, come to think of it, I bet Poe read):

But what is perhaps worse is, that we are accustomed to pronounce, that that soil, which will not produce the crop of which we have attempted to make it fertile, is fit for nothing. The majority of boys, at the very period when the buds of intellect begin to unfold themselves, are so accustomed to be told that they are dull and fit for nothing, that the most pernicious effects are necessarily produced. They become half convinced by the ill-boding song of the raven, perpetually croaking in their ears…

I’m going to force myself to stop there because I don’t want all my posts to be about education. Instead let’s skip ahead to this sentiment from another essay, which while hardly a brilliant insight still doesn’t get said enough:

Monumental records, alike the slightest and the most solid, are subjected to the destructive operation of time, or to the being removed at the caprice or convenience of successive generations. The pyramids of Egypt remain, but the names of him who founded them, and of him whose memory they seemed destined to perpetuate, have perished together. Buildings for the use or habitation of man do not last for ever. Mighty cities, as well as detached edifices, are destined to disappear. Thebes, and Troy, and Persepolis, and Palmyra have vanished from the face of the earth.

"Thorns and brambles have grown up in their palaces: they are habitations for serpents, and a court for the owl."

There are productions of man however that seem more durable than any of the edifices he has raised. Such are, in the first place, modes of government. The constitution of Sparta lasted for seven hundred years. That of Rome for about the same period. Institutions, once deeply rooted in the habits of a people, will operate in their effects through successive revolutions. Modes of faith will sometimes be still more permanent. Not to mention the systems of Moses and Christ, which we consider as delivered to us by divine inspiration, that of Mahomet has continued for twelve hundred years, and may last, for aught that appears, twelve hundred more. The practices of the empire of China are celebrated all over the earth for their immutability.

This brings us naturally to reflect upon the durability of the sciences. According to Bailly, the observation of the heavens, and a calculation of the revolutions of the heavenly bodies, in other words, astronomy, subsisted in maturity in China and the East, for at least three thousand years before the birth of Christ: and, such as it was then, it bids fair to last as long as civilisation shall continue. The additions it has acquired of late years may fall away and perish, but the substance shall remain. The circulation of the blood in man and other animals, is a discovery that shall never be antiquated. And the same may be averred of the fundamental elements of geometry and of some other sciences. Knowledge, in its most considerable branches shall endure, as long as books shall exist to hand it down to successive generations.

It is just therefore, that we should regard with admiration and awe the nature of man, by whom these mighty things have been accomplished, at the same time that the perishable quality of its individual monuments, and the temporary character and inconstancy of that fame which in many instances has filled the whole earth with its renown, may reasonably quell the fumes of an inordinate vanity, and keep alive in us the sentiment of a wholsome diffidence and humility.

I can’t read this without hearing Julia Ecklar’s anthem treatment of Leslie Fish’s Hope Eyrie. So here you go.

His essay “Of Leisure” isn’t quite so excerpt-friendly, but is wise. Leisure is valuable. Decadence born of inequality is bad, yes, but mainly because that’s resources that could be used more efficiently if spread more evenly. We undervalue leisure—starting in school, he points out, where kids are “put to work learning” when they’d typically learn more by being allowed to play. Wait. Shoot. I said I was going to stop with the education stuff. Godwin seems to have had trouble letting go of it too.

Let’s skip ahead again to another beautiful sentiment. In his next essay, “Of Imitation and Invention,” he rebuts the Biblical claim that “there is no new thing under the sun.” No. Everyone is an inventor, and together we are remaking the world. This is most obvious, Godwin says, when you’re in an airplane and looking down at how we’ve literally reshaped the earth. This is an impressive insight given that airplanes very much did not exist yet.

The thing most obviously calculated to impress us with a sense of the power, and the comparative sublimity of man, is, if we could make a voyage of some duration in a balloon, over a considerable tract of the cultivated and the desert parts of the earth. A brute can scarcely move a stone out of his way, if it has fallen upon the couch where he would repose. But man cultivates fields, and plants gardens; he constructs parks and canals; he turns the course of rivers, and stretches vast artificial moles into the sea; he levels mountains, and builds a bridge, joining in giddy height one segment of the Alps to another; lastly, he founds castles, and churches, and towers, and distributes mighty cities at his pleasure over the face of the globe. "The first earth has passed away, and another earth has come; and all things are made new."

But things less visible from hypothetical long-distance air travel are continually evolving, too. Language, for example. As Godwin puts it, maybe in your whole life you only manage a single good and original sentence, or a single original word. Even then, that act of creation lives on, echoed by generation after generation. You’ve added something new and lasting to the world.

In later essays, he’s added just such a quirky phrase to my vocabulary: the virtue of “self-complacency.” The more common term at the time was “self-love,” and that concept he’s a little suspicious of. Benevolence, he says, is and ought to be directed outwards, toward others. He’s more positive about “self-esteem,” a phrase that people had just started using in its modern sense. But “self-complacency” he comes back to again and again. Just as he wants to persuade you that humanity is good, he wants each human to believe themself good. You can, and should, want to be better. But at the same time, always remember: you’re already good enough.

(And as a corollary, he says, we should probably not be trying to in any sense “break” students. But we’re not talking about education.)

His first essay to discuss the distinction between self-love and self-complacency has an image I’ve found very helpful. Maybe a more apt word is “healing”.

The principal circumstance that divides our feelings for others from our feelings for ourselves, and that gives, to satirical observers, and superficial thinkers, an air of exclusive selfishness to the human mind, lies in this, that we can fly from others, but cannot fly from ourselves. While I am sitting by the bed-side of the sufferer, while I am listening to the tale of his woes, there is comparatively but a slight line of demarcation, whether they are his sorrows or my own. My sympathy is vehemently excited towards him, and I feel his twinges and anguish in a most painful degree. But I can quit his apartment and the house in which he dwells, can go out in the fields, and feel the fresh air of heaven fanning my hair, and playing upon my cheeks. This is at first but a very imperfect relief. His image follows me; I cannot forget what I have heard and seen; I even reproach myself for the mitigation I involuntarily experience. But man is the creature of his senses. I am every moment further removed, both in time and place, from the object that distressed me. There he still lies upon the bed of agony: but the sound of his complaint, and the sight of all that expresses his suffering, are no longer before me.

…

Is it then indeed a proof of selfishness, that we are in a greater or less degree relieved from the anguish we endured for our friend, when other objects occupy us, and we are no longer the witnesses of his sufferings? If this were true, the same argument would irresistibly prove, that we are the most generous of imaginable beings, the most disregardful of whatever relates to ourselves. Is it not the first ejaculation of the miserable, "Oh, that I could fly from myself? Oh, for a thick, substantial sleep!" What the desperate man hates is his own identity.

While you are feeling deep empathy for your friend suffering in bed, you are more or less the same person. As you walk away, it might feel like a betrayal. But it’s the opposite. You’re the part of the sufferer that gets to walk away. That’s part of the promise and purpose of your empathy. You merge with the sufferer for a time, and now the healthy person walking away is a successor self to the sick one, not just to the healthy one who walked in.

Then he talks about free will, and gets it right. That’s gonna need to be a separate blog post, but he gets it right.

(Ed:

)

As we keep going, he notes that the essays are in roughly descending order of confidence. The later ones are more specific, and more likely, he says, to be wrong. For example, in one he argues that voting shouldn’t be secret and anonymous. He makes a pretty good case, but it’s hardly a universal a priori law.

Now we get to science. He starts by attacking phrenology, the pseudoscience of determining people’s personalities and abilities by looking at the shape of their head. He doesn’t quite manage to coin the word pseudoscience— he calls phrenology a “pretended science.” He describes how phrenologists consistently fail to make successful advance predictions, and then find ways of retroactively justifying their failed ones. He also makes the now-standard case against phrenology, that it’s just an excuse for bigots to claim false limits on the potential of people they dislike.

Then he moves on to debunk another science: astronomy. This is a helpful lesson in how one needs to remember to be just as skeptical of skepticism as anything else. I was nodding along happily to the phrenology argument, because I knew the conclusion was right. But it was actually not a great argument. You can’t debunk a science by pointing out that the motives of its adherents are ideologically impure. Refuting Social Darwinism does not refute Darwinism. Or, to get more absurd, suppose someone uses the claim that 123 is the square root of 15129 as part of making an ideological argument. No matter how compelling or vile the ideology, it has no bearing on the math. The only way to check the math is to check the math.

Just as Godwin disliked the reductiveness of phrenology, he dislikes astronomy because it reduces humanity to a tiny speck in a vast universe. So he defends humanity by attacking astronomy. How can we be so confident about the sizes and distances of celestial objects, he asks, when we can’t even measure the height of a mountain consistently? How can we trust the cosmological inferences an astronomer makes after looking at a few dots of light through a telescope lens? Naively extrapolating using math can lead you astray, he says. For example, Malthus’s equations imply that in a hundred years there will be millions of people living in New York! Obviously absurd.

So let’s add “claimed that stars weren’t real” to the list of cautionary tales from the life of our modern Prometheus. It’s certainly true that naively applying math can lead you astray. But that danger is nothing compared to naively applying…well…basically anything else, but especially ideology.

Part 5: “the serene twilight of a doubtful immortality.”

Godwin’s essays contrast the fleeting joy of fame with the enduring gift of a legacy. Even as he wrote them, he knew he was himself becoming an illustration. The world was forgetting him. The celebrated essayist William Hazlitt wrote, around the same time:

The Spirit of the Age was never more fully shewn than in its treatment of this writer—its love of paradox and change, its dastard submission to prejudice and to the fashion of the day. Five-and-twenty years ago he was in the very zenith of a sultry and unwholesome popularity; he blazed as a sun in the firmament of reputation; no one was more talked of, more looked up to, more sought after, and wherever liberty, truth, justice was the theme, his name was not far off:—now he has sunk below the horizon, and enjoys the serene twilight of a doubtful immortality. Mr. Godwin, during his lifetime, has secured to himself the triumphs and the mortifications of an extreme notoriety and of a sort of posthumous fame. His bark, after being tossed in the revolutionary tempest, now raised to heaven by all the fury of popular breath, now almost dashed in pieces, and buried in the quicksands of ignorance, or scorched with the lightning of momentary indignation, at length floats on the calm wave that is to bear it down the stream of time. Mr. Godwin's person is not known, he is not pointed out in the street, his conversation is not courted, his opinions are not asked, he is at the head of no cabal, he belongs to no party in the State, he has no train of admirers, no one thinks it worth his while even to traduce and vilify him, he has scarcely friend or foe, the world make a point (as Goldsmith used to say) of taking no more notice of him than if such an individual had never existed; he is to all ordinary intents and purposes dead and buried; but the author of Political Justice and of Caleb Williams can never die, his name is an abstraction in letters, his works are standard in the history of intellect. He is thought of now like any eminent writer a hundred-and-fifty years ago, or just as he will be a hundred-and-fifty years hence. He knows this, and smiles in silent mockery of himself…

I quoted this to my spouse, and she said, “oh, like Stephen King.” Exactly. I don’t think people will still be reading King’s books in two hundred years, and he probably agrees. But they’ll be living in a world King helped shape, and I hope he knows that too.

In writing this whole long post about the guy, I’ve said practically nothing about the guy, per se. What was his childhood like? How did he make a living? What drove him to be a prolific writer, and so ahead of his time? Nah. Not going to go into any of it. I want to honor his legacy, not try to resurrect his fame. Maybe Mary Shelley’s dedication really did do him the most justice. So I’ll raise a glass—

To William Godwin, author of Political Justice, Caleb Williams, etc.