Here’s the story of how, as a teenager, I spotted that a nonprofit was wasting millions of dollars on accidentally harming disadvantaged high-school students, and then completely failed at doing anything about it.

I think this must have been in 2002, maybe 2003. I was 16ish, and had dropped out of high school to focus on my studies. This included taking a pair of one-week-long summer courses at Johns Hopkins University—one was “political science” and the other “political philosophy.” I don’t exactly regret it, but it was full of little disasters. I spent my free time trying to date someone who, I found out almost 20 years later when we reconnected, was not into men. I got pneumonia, which was misdiagnosed and went untreated by people working for a university with a world-famous medical program. In the philosophy class I tried to make a joke about “paternal” and “parental” being anagrams and totally bombed.

For the political science class, we spent a day in Washington, D.C. that was mainly meant as a “career day” sort of thing—we set up in a random conference room, and people who did different kinds of government or government-adjacent work came in and talked about it. One of them worked for a nonprofit that had started in D.C. and was at the time mainly funded by federal grants. And, at the time, it was named College Summit.

College Summit, the speaker told us, set up shop at a small number of area high schools, chosen for their low rates of sending graduates to four-year-colleges. It aimed to fix that by giving support to their seniors, specifically to do with the college application process. Early in the year, students would go to a four-day summit where they’d learn about colleges and financial aid, and fill out their first actual college application. Then they’d get support with the process for the rest of the year, and were encouraged to mentor their classmates.

He handed out brochures that described the amazing success of their program. I don’t have the brochure, but I do have the internet archive of their website at the time, and this was back when websites were mostly just online versions of a brochure.

If you are already screaming internally, congratulations. It took me at least a few minutes longer.

It hit me when the speaker started explaining that one clever feature of the program is you have to apply to get into it, in a process deliberately made to resemble the college application process, so that kids would start getting good practice right away. So that meant, I thought, that the College Summit program didn’t include the entire class, only the ones eager and able to get into a program called College Summit. I looked back at the statistics. 46% of students at that income level go to college, but 79% of students enrolled in College Summit do. Oh no.

Of the 46% of students who were going to go to college anyway, how many of them would enroll in a college prep program? Probably just about all of them. Of the remaining 54%, the ones who would otherwise have not applied to any colleges, or not been accepted by any of them, how many would apply to College Summit and be accepted? It seems like it would be very few.

Consider a hypothetical world where College Summit has absolutely no effect, but students don’t know this going in, so 90% of the college-bound students attend and 20% of the others do. Out of a 100 students, 46 were in the college-bound group, so 41 of them are in College Summit, and 20% of the remaining 54, 11 students, are there too. Since College Summit, in our hypothetical, isn’t changing anybody’s destiny, that means that out of our cohort of 41+11 = 52 students, 41 of whom go to college, for a success rate of…79%. (If you’re wondering how I worked backwards to get this result, I didn’t, I just picked numbers that felt right and got really lucky on the first try.)

So, either the brochure’s statistics were wrong, or the whole thing wasn’t working at all.

I felt really bad about thinking like this. Here this person was, not so much even pitching their specific nonprofit as pitching the idea of working for a nonprofit, and I was sitting here, in my privileged bubble, judging them for trying to help poor kids get stuff I was practically being handed. So I waited until after the Q+A before I approached him. (I don’t remember the speaker’s face or name, which is probably for the best, but I think it was a recent college grad, not the founder or anything. Probably.)

“I didn’t want to inflict this question on the whole class,” I started out, like the adolescent guiltmonster I was. “But don’t these statistics kind of imply you’re not improving outcomes?”

The conversation did not go well. I remember at one point saying something like “the students who get in to your program are probably the ones with better support from parents and teachers,” and my own teacher breaking in to say “No, no, many of these kids don’t have any support! That’s the point!” and shaking her head at my naivety. I also remember the end of it, when I said, in desperate confusion, “But you’re supported by grants! Hasn’t anybody ever audited you?”

“What do you mean by ‘audited’?”

“Hasn’t anybody ever come to you and challenged you to argue that you were having an effect that was worth the investment?”

“No,” said the speaker, looking at me disgustedly (note though that my adolescent memory is an unreliable narrator on shame-related matters). “Nobody has ever done that.” He might not have been completely correct, but I was pretty sure he wasn’t being sarcastic.

And Then I Did Nothing

I mean, I was a teenager. Even with time to think, I couldn’t put the argument into words very well. The most I could persuade myself of, with any confidence, was that the brochure didn’t make the case it thought it was making. But maybe it was just a badly-written brochure, right? Maybe there were actual good statistics out there that hadn’t made it in. It was not the level of confidence I needed if I was going to, say, write to Congressional Republicans and tell them to investigate and maybe cut funding to the employer of someone who’d just volunteered his time to try to teach me how to help others.

And, I must have thought, Republicans are running the government now. Surely they’d notice.

I did nothing. Until yesterday I had even persuaded myself that College Summit must have been shut down shortly afterward. I’d probably misremembered seeing some headline about Republicans wanting to cut TRIO programs.

But yesterday I realized I was living in the future, and could pretty easily do the research that had seemed impossible back then. And sure enough, behold! The good news is that someone had, eventually, done that audit thing. The bad news is that it took fifteen more years. In 2011, after the program had expanded to over a hundred schools, and I think switched mostly to private funding, they hired an independent evaluator, the American Institutes for Research, to do a five-year study on their effectiveness and impact. And, after those five years, AIR had its finding. Here’s the worse news.

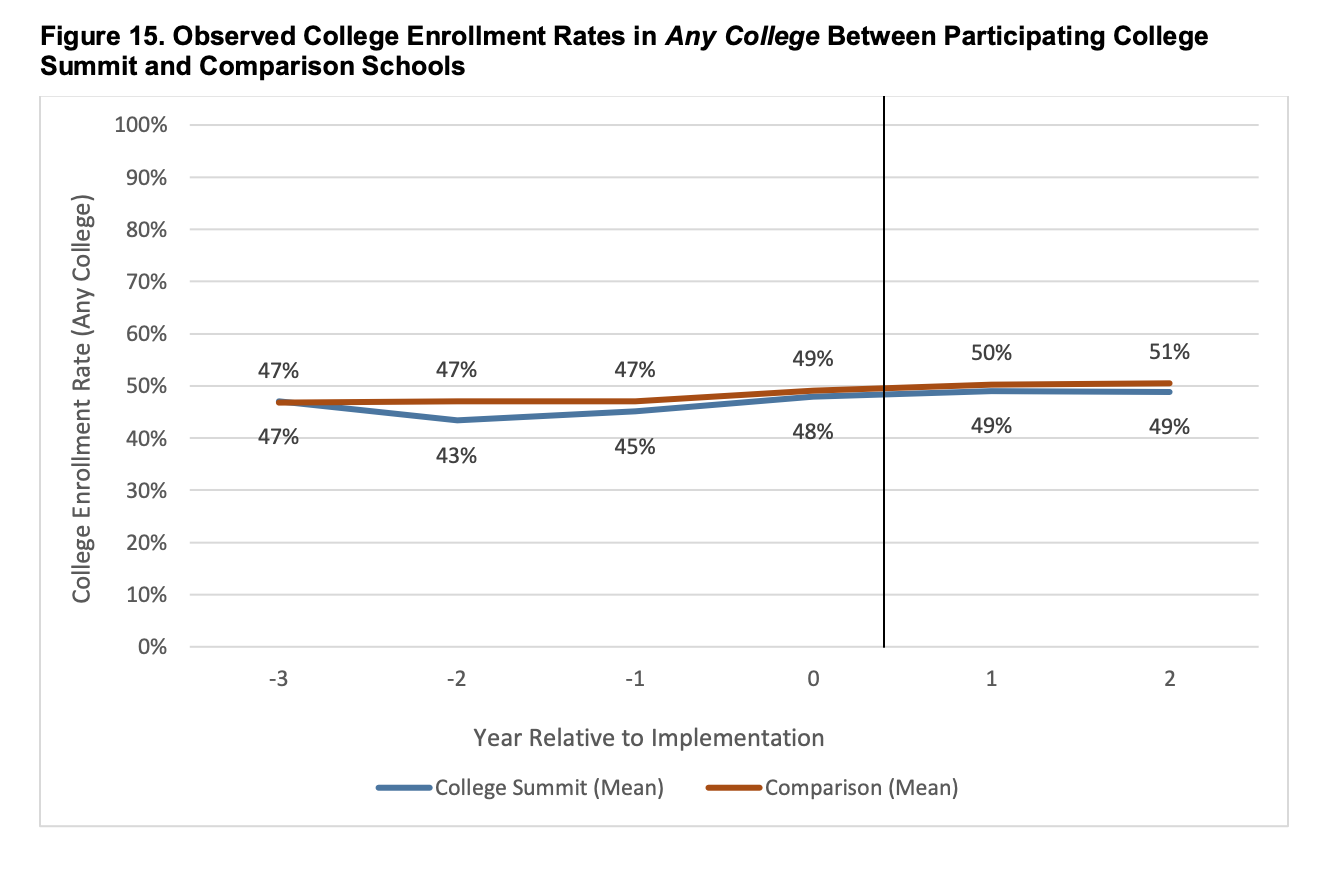

We found no statistically significant difference between treatment and comparison groups on any college or in a four-year college enrollment rates. This was unexpected…

And Neither Did They

Yes, after more than 20 years of College Summit being a thing, someone had finally asked the right question: are students at participating schools more likely to go to college? And, after getting paid for five years to ponder this, they’d checked the answer. No.

Their paper goes on to flail a little the way studies do when they get an unexpected null result and try to hack it into being not that. Does it look different if we restrict it to four-year colleges? It’s a nationwide program; are there any individual states where it looks different? What if we only checked outcomes for Libras? But any way they sliced it, that blue line stayed stubbornly right below the red one. No matter whether you compared a school to itself before the program, or paired it to a similar school with similar students, it just wasn’t doing any better.

Why wasn’t College Summit having any positive effect? The AIR paper professes bafflement, but drops a few hints. Here’s one:

According to participation data, College Summit served as few as one high school senior in one high school…

So now, more than ever, I believe that claim that the program was selective and imposed an intentionally onerous application process. It’s filtering for all but the most likely to succeed.

Here’s another hint: they did a survey asking for suggestions for improvement. The main theme was this:

Greater Presence of College Summit Staff

Ten respondents noted a greater need for support from College Summit. Many of these respondents specifically expressed that a greater presence and involvement of College Summit staff in the buildings was needed. For example, one College Summit coordinator said: I believe College Summit should be more involved at the school level. We are often at times told to report out data for College Summit, but rarely do we receive much support from our College Summit staff at the school level. If students saw College Summit staff being more active in the building—whether for FAFSA, college fairs, or even classroom presentations—it will help the students take the program more seriously.

In at least ten schools, after the summit itself, College Summit rarely actually…did…anything, other than check in on how well their “ask students whether they want to go to college” system was doing at predicting whether they ended up going to college.

The other meta-hint within this hint is that the survey wasn’t sent to students themselves, just faculty. This was not a program good at receiving feedback from those actually affected.

The End

…Or Is It?

College Summit didn’t go away after that, it just changed its name and tweaked its emphasis. It’s now PeerForward (spaces are so last century), and its main goal is to identify the best students to act as Peer Leaders for the rest, plus help students apply for scholarships, rather than the colleges themselves. And their website quotes a statistic that actually claims to compare like with like!

Compared to similar schools, PeerForward high schools achieve, on average, a 26% higher completion rate of financial aid applications.

Hooray! It might actually be doing something now! Although, if you scroll down on their impacts page, they’re still doing the same statistical shenanigans for other metrics. “74% of high school student Peer Leaders enroll in college!” So…you’ve gotten slightly worse? In terms of the one outcome we care about? Oh well.

As of 2022, they grossed 13.6 million dollars in grants and donations, according to their tax filings. That would’ve been enough to give every Peer Leader four years of Pell grants.

“They got away with it.” That doesn’t seem like the right framing. There might’ve been some grifting going on somewhere (did AIR really need five years to crunch those numbers?) but I’m sure most of the people involved were far from getting rich. They were just doing a low-paying job with sullen teenagers, and maybe also with an imperfectly-suppressed awareness that they weren’t even doing the good they’d wanted to do with their careers. No winners here. I’d rather just say that what looked broken in 2002 is still broken today.

They’re Everywhere

College Summit’s longevity is evidence that it’s nowhere near unique. The nonprofit ecosystem allowed it to thrive. Their results page, right next to those unwittingly damning numbers, lists some of the “honors” they’d received from other organizations, none of which seem to have noticed their complete lack of impact. Tina Rosenberg, a Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist and advocate of “rigorous reporting about responses to social problems,” wrote a 2016 opinion piece in the New York Times praising College Summit. The next year, AIR published its findings. The year after that, David Bornstein, Rosenberg’s co-founder of the rigorous responses project, wrote a followup article that did not mention the AIR study and again uncritically praised the now-renamed company.

That’s a whole lot of people whose job was to do a very basic check of the numbers, and none of them did it. I am bragging, and want you to be impressed with me, when I tell the story of how I spotted the problem within minutes as a teenager. But don’t be that impressed. This wasn’t a feat of mathematical genius. I’d like to think that most rooms full of teenagers taking advanced classes contain one who would ask the right question.

And you shouldn’t be impressed at all that it took me like ten minutes yesterday to find that AIR study and scroll to the “impact” section. That was super easy. So what’s Bornstein’s excuse?

What’s Going Wrong?

Privilege Guilt: I have to imagine that most of these reporters and philanthropists had, in their heads, some version of that shame-ridden 16-year-old who “didn’t want to inflict” his analysis on the class. If people are doing something noble, it’s ignoble to criticize them, right? Only the teachers and students had the moral standing to object, and they didn’t have enough information or authority.

Sunk Costs: Once you’re already working for College Summit, what’s the upside for you in noticing that its numbers don’t add up? If you try to leave it for another nonprofit that doesn’t look similarly flawed, that’s still a lot of lost time and the risk of the same thing happening again. It’s not obviously better than gambling that either your doubts are mistaken or the program’s about to start working.

Coordination Traps: If College Summit had avoided publishing misleading numbers, that would just mean a less honest nonprofit in the same space would get the grants and donations. Acting alone, it’s not obviously correct to be honest if the environment is already dysfunctional enough, which of course means it stays dysfunctional.

Innumeracy: Most reporters don’t understand what a percentage is. 1 They know they’re important and that your reporting is more “solid” and “rigorous” if it includes them. But they don’t have a clear sense of what a percentage implies, or what other percentages are necessary to put that one into context. One rarely gets the impression that a reporter who uses the number 56% has the number 44% somewhere in the back of their mind.

Anyone reporting on College Summit in the past twenty or thirty years has seen some variant of that line from the brochure. They could have asked, as followups, “what percentage of seniors in participating schools end up in College Summit?” and “what percentage of the other seniors have enrolled in college?” Then they could have done some simple arithmetic. But that’s just not what they do. The very idea of trying seems suspect to them, I think. Thus the lack of accountability that creates the bad incentives that create the coordination trap.

What’s the harm?

I claimed up at the top that College Summit/PeerForward was doing harm, not merely being neutral. So I’ll make that case explicitly.

It’s mostly about opportunity cost. To become a participating school in College Summit, you need an administration that recognizes a problem and is proactive about finding and vetting solutions. Then they need to pay College Summit $10,000 out of the school budget, teachers need to spend time and attention on it, and students need to spend even more time and attention on it. All of these resources could have been spent on an intervention that did something, but they weren’t. So College Summit was, and PeerForward is, a trap that thwarts high school faculty trying to get help for their students.

I’ve already alluded, as well, to the guess that if people hadn’t donated to College Summit, they might have donated to a scholarship fund targeting the same demographics. That’s another flavor of opportunity cost.

There’s also the fact that college enrollment rates seem to pretty consistently be about 1% lower in College Summit schools. That might be all statistical noise, or opportunity cost, but they might very well be having a slightly net-negative effect beyond all that. Establishing a “college track” very early on in the year, one with limited slots, might be demoralizing to everyone who doesn’t get in. And the ones who do get in get to go to a cool four day summit, sure, but then they’re told to expect support that they don’t always actually receive. So both tracks might have their initiative dulled a bit.

Also, if you take their current statistical claims at face value, they imply that they’re getting students to apply for financial aid when they don’t intend to use it, thereby slowing down the process for other students who actually need it. So they may be harming students in other schools, too.

Almost no one is evil. Almost everything is broken.

Harsh Lessons I Learned at JHU

Even if her friends are privately telling you “Don’t despair! She definitely likes you!” she still might be a closeted lesbian.

Mere proximity to the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine does not mean that the student health center provides high quality care.

Nobody necessarily audits nonprofits in anything approaching a rigorous manner.

In summary, there were fewer shortcuts in life than I thought. You can’t go by the label. People express confident judgments that can lead you off a cliff. If it matters to you, you have to actually look at it yourself. It shouldn’t be this way. Nobody has time to think critically about everything that affects them. But that’s the way it is.

In 2014, we got what should have been a harmless wakeup call. Nate Silver, who does sports and politics predictions, gave Brazil at various points between a 40% and 45% chance of winning the World Cup. This was much higher than the chance he gave any of the other teams. However, Brazil did not win the World Cup, losing by a large margin in the semifinals after their star player was injured, even though Silver’s model still had them as a 2:1 favorite. Here are some headlines this generated:

45% was a big number, you see. No other team got a number so big. So it indicated very strong confidence that Brazil would win. That’s the job of a reporter—convert numbers into words. So when that 55% chance of Brazil losing happened, that meant Nate Silver—nay, the entire concept of doing a math while doing a journalism—had been discredited.

(The confusion about how a 2:1 favorite can lose by a blowout margin is a slightly more sophisticated error, to do with correlated probabilities, that I won’t go into here).

Their ignorance had serious consequences in 2016. When Silver’s model gave Trump a 20% chance of winning, given the polls, most journalists simply didn’t understand what that meant. They treated his chances as negligible, and therefore made the editorial decision to be very hard on presumptive winner Clinton, especially in the final two weeks, so as to be more relevant and not look biased.

If you play Russian Roulette, you have a 20% chance of dying.