William Godwin's Libertarian Free Will

Title is a dumb pun that, appropriately, I couldn't resist.

In my post on William Godwin and his Thoughts on Man, I mentioned that one of his essays gets Free Will right, and promised to explain why. So now I have to.

(see also or instead: Eliezer Yudkowsky’s How an Algorithm Feels From the Inside and Dissolving the Question on the same topic).

Godwin’s essay, Of The Liberty of Human Actions, is part of a collection in defense of humanity. He argues against phrenology in the same collection. So you might expect him to argue against determinism in the same spirit. Nope. In this essay, he doesn’t argue against anything. Here’s my attempt at modernizing what he says. Disclaimer that none of this is original to me, not just the directly-from-Godwin stuff, to the point where I may be accidentally plagiarizing entire metaphors.

We know, intellectually, that every effect has a cause, even the decisions made in our minds. Even if you think you don’t know this, you do. You find it worthwhile to communicate with people. When you communicate to somebody, you’re causing an effect in their mind. You’re influencing their decisions.

For someone to actually believe that our choices are divorced from cause and effect, they would need to believe that all of their actions are being dictated by something with no knowledge of their context. If you happen to raise your hand to catch a ball, well, you would’ve done that even if there were no ball. If you change your entire life after a religious experience, that’s just a coincidence or something. There are philosophers who’ve tried to make this hypothesis make sense, but to most of us it seems inherently absurd.

All the stuff about mind/brain dualism, whether metaphysics exists outside of physics, terms like “biological/genetic/astrological determinism”…all of that’s a red herring. It’s all questions about what kinds of cause and effect play the most important role in our decisions. No matter your model of reality, it still has something causing us to do what we do.

But even after acknowledging all of that, Free Will still feels like an open problem! Why?

Because we intuitively feel like our minds are special. That’s what it comes down to. We experience ourselves as free.

Philosophers talking about free will almost always make the mistake of trying to reconcile these two things—the primacy of cause and effect in our reasoning, and the intuitive sense of freedom in our personal experience. This is both unnecessary and impossible. “Cause and effect” and “free will” aren’t hypotheses, or beliefs. They’re ways of thinking, and they’re appropriate in different domains.

Here’s a separate example to illustrate what I mean by different domains. A basketball player throws a ball, and it goes through the hoop. Why did that happen? We might answer with a physics model explaining the ball’s path. We might answer by explaining the rules of basketball. We might answer with a discussion of why that player is good at shooting hoops, or the tactical failure of the other team on that play. We might be more zoomed out than that, and giving the answer “gravity,” or hypotheses for why humans evolved to be pretty good at throwing things.

The cliché thing to say here would be that all of these answers are right. That’s a little wrong, though. In a given context, only one of them is appropriate, and that’s important! If a player is asked in a post-game interview why their opponents scored so many points, and they answer “gravity,” they have failed to answer the question.

Suppose Alice punches Bob. Was it of her own free will, or for some other reason? This is not a question with only one answer! The right answer will always depend on what you’re trying to do. It usually (always?) falls into one of these categories:

Assigning Blame. When should we consider punching a crime? High-level answer: When doing so creates an incentive that leads to a reduction in harm. If Alice punched Bob to save her own life (someone with a gun to her head ordered her to, or it was in self-defense), no punishment or censure could outweigh that, so there’s no point in holding her responsible. If she punched Bob because she was hallucinating that he was a bear, incentives against hitting humans wouldn’t have had any power to dissuade her. If she’s fundamentally incapable of understanding incentives, again, there’s no point to them. If nothing like that applies, then we should hold her responsible, because if we hold people responsible for their actions they’ll overall take better actions. The same reasoning applies if the law in question is a commandment in the Bible, say. Every “thou shalt” exists for a reason, and if circumstances invalidate that reason, the commandment isn’t relevant.

Science. You might be trying to get at the root causes of the punch, either out of curiosity or as a step toward reducing future punchings. If that’s what you’re doing, “free will” more or less means “outside the scope of this analysis.” If you’re studying a neurological syndrome that increases aggression, the first question you’re interested in is “was this caused by this syndrome or not?” If you’re studying sociological causes of violence, the neurological condition instead goes into the “not” category. Often the question is more like “to what extent was the punch caused by” whatever, because science is a domain where complicated and messy answers are still useful. Unlike, say, if you’re in a jury giving a verdict.

Storytelling. You might be trying to get inside Alice’s head. You might want to build empathy, or improve your intuition around what she’s going to do next, or hear an exciting story with violence in it. In this case, any explanation that starts with “I wanted to punch him because” is free will.

Introspection. You might be Alice. If you’re thinking back on why you did something, it’s rarely useful to treat it as outside of your control. Barring really extreme situations, you’ll learn the most from your experience if you think in terms of free will, even if you’re also acknowledging other factors. “I had adrenaline flooding my body due to a neurological condition, which caused me to feel a certain way, and I chose to express those feelings with physical violence.”

Our intuitive sense of our own free will comes from this last one. In the domain of introspection, it’s almost always most useful, and therefore correct, to say that you have agency. So whenever you’re looking at your mind “directly,” you see it having free will. It can feel like this direct observation should take precedence over all the other modes. Like it should outweigh them, or at least be weighed against them. But that’s wrong. They’re different domains. “Did you choose to do that or was it because of external factors?” is as much of a nonsense question as “Did you sink that shot because you’d been practicing, or because of physics?”

When the chain of cause and effect doesn’t pass through any thought process you have introspective access to (Eve lifts your arm and hits Bob with it), then and only then does it stop feeling like free will. Because introspection isn’t relevant then.

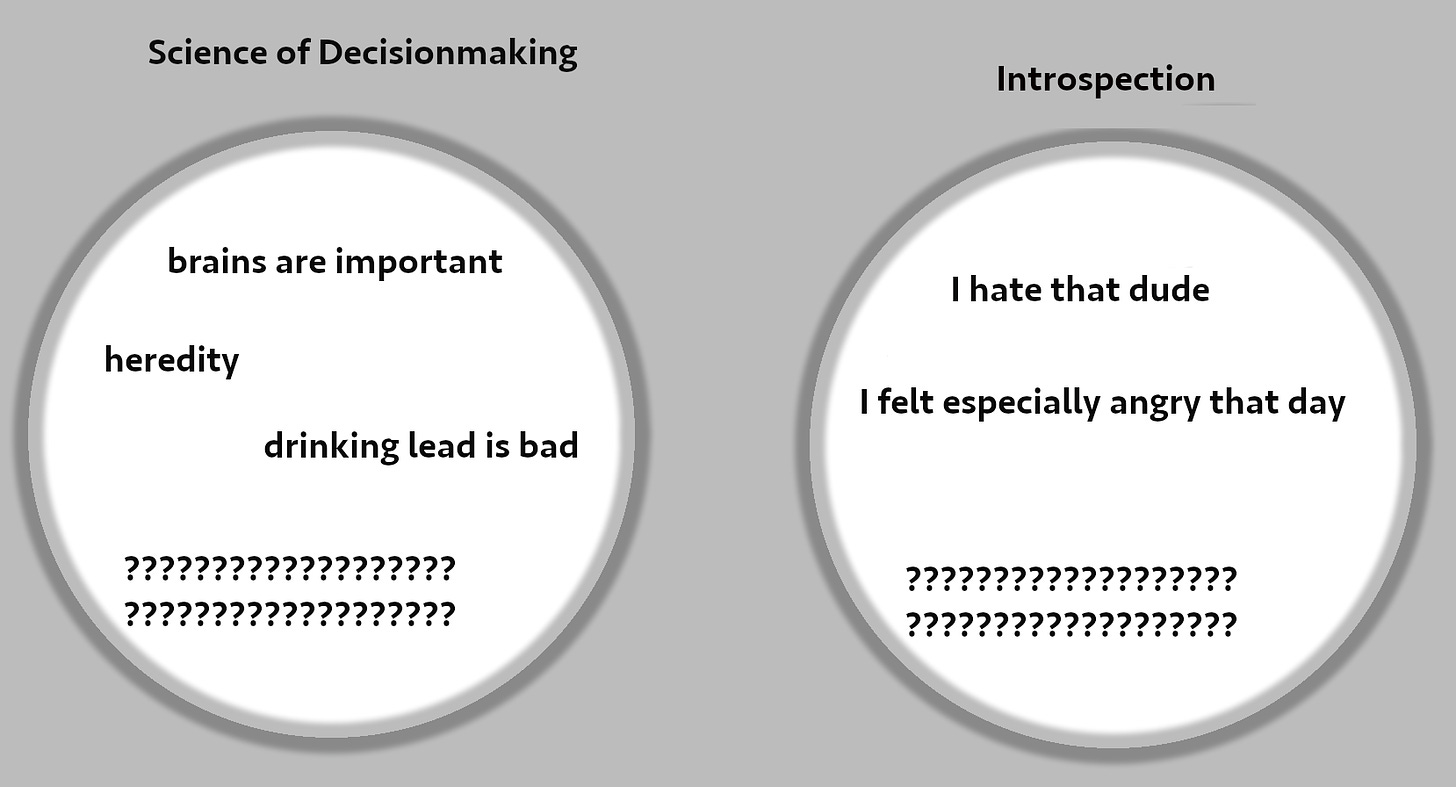

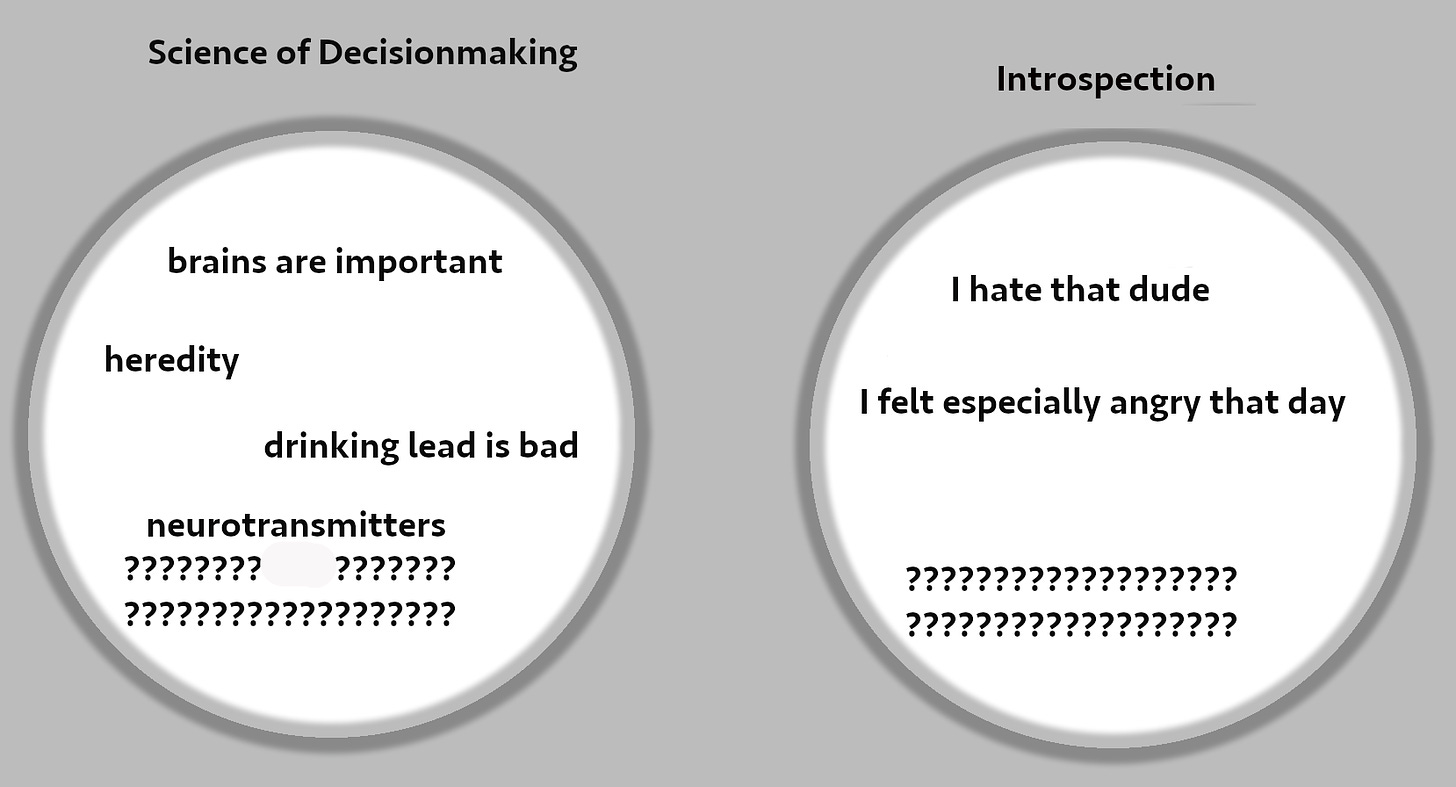

There’s an illusory feeling that science is encroaching on, or even debunking, our concept of free will. That comes from the way we keep learning more things about the causes of human decision-making, so we end up being able to more profitably spend more time in the science domain when reasoning about people. But that’s not actually the science domain expanding at the expense of any of the others. When we didn’t know about neurotransmitters, the empty space that left in our model of the world wasn’t filled with introspection, or morality, or stories. It was empty space within the science domain.

Before We Discovered Neurotransmitters

After We Discovered Neurotransmitters

Science didn’t steal any of introspection’s territory. It just got a tiny bit less mysterious. Learning things about yourself, say in therapy, likewise doesn’t encroach on science.

The same is true for every pair of domains. We sometimes feel like they’re in competition, but that’s almost always incorrect. Scientific explanations for someone’s behavior, beyond a medical description of their symptoms, shouldn’t have any relevance in a court of law. There’s often a moral panic when someone publishes a study about human decision-making— “scientists are eroding personal responsibility!” People even sometimes talk like they can debunk a scientific paper by appealing to moral law.

(There are exceptions. Storytelling and introspection have some overlap, and sometimes you really can refute a scientific theory of your behavior by explaining what you were actually thinking).

To belabor the point, let’s go back to the basketball shot going in the hoop. Our knowledge of basketball can inform our knowledge of physics, and vice versa. They’re not separate magisteria. I’m not going to google it but I feel very confident a priori that a pop-sci book exists called something like “The Physics of Basketball.” But the interaction between the two is purely cooperative. There’s no competition over territory. If we ever find ourselves asking “is this caused by physics or basketball?” something’s gone wrong.

What I found impressive about Godwin’s essay wasn’t mainly that his ultimate conclusion agrees with mine. Plenty of philosophers end up with some kind of “compatibilist” position on free will. What I like is on the meta-level, the way he approaches it. He argues that no relevant questions of fact are actually involved. That done, instead of dismissing the entire question in a fit of naive logical positivism, he reframes it. When, and how, is the deterministic view useful? When does it have good consequences to think this way? And, conversely, when and how is the “sense of liberty” useful?

This is almost always the right answer, after a debate has been going on for longer than a generation, and still nobody can even describe an experiment that would settle the issue. If we still haven’t figured out the crux of our disagreement—we don’t actually disagree! We’re just attached to different strategies of thought, and we should each learn the benefits of the other’s.

I love this guy’s writing, so I’ll end with a couple of excerpts from the essay.

Here’s part of his ode to free will:

From hence there springs what we call conscience in man, and a sense of praise or blame due to ourselves and others for the actions we perform.

How poor, listless and unenergetic would all our performances be, but for this sentiment!

…

It is either the calm feeling of self-approbation, or the more animated swell of the soul, the quick beatings of the pulse, the enlargement of the heart, the glory sparkling in the eye, and the blood flushing into the cheek, that sustains me in all my labours.

And here’s part of his ode to determinism:

We shall however unquestionably, as our minds grow enlarged, be brought to the entire and unreserved conviction, that man is a machine, that he is governed by external impulses, and is to be regarded as the medium only through the intervention of which previously existing causes are enabled to produce certain effects. We shall see, according to an expressive phrase, that he "could not help it," and, of consequence, while we look down from the high tower of philosophy upon the scene of human affairs, our prevailing emotion will be pity, even towards the criminal, who, from the qualities he brought into the world, and the various circumstances which act upon him from infancy, and form his character, is impelled to be the means of the evils, which we view with so profound disapprobation, and the existence of which we so entirely regret.

I love this! I feel much better about this whole argument now that I can be on both sides of it. Can you post a link to Godwin's essay? Or did you and I missed it?