On April 14th, 2009, a Canadian warlock discovered that his magic had stopped working.

15-year-old Vitalik Buterin was obsessed with the massively-multiplayer online fantasy game World of Warcraft, which had just received an update. Patch 3.1.0 advanced the plot (the Old God Yogg-Saron threatens to break free from Ulduar, unless some brave adventurers can save the world), but it also tweaked the rules of the game a bit. This is common in WoW. In the game, you choose a character class for your player avatar, each of which has unique abilities, strengths, and weaknesses. Warrior, mage, and priest are three of the thirteen options. (Yes, priest. In games in the Dungeons and Dragons idiom, it’s taken as a given that any religious figure can perform miracles on demand, usually specializing in healing, so they’re good to take along when fighting monsters. Otherwise, I mean, what would be the point of religion?) Players expect all options to be equally powerful, at least when played correctly. It’s not many people’s fantasy to be the sidekick. So the company that makes and runs WoW, Blizzard, does its best, but it’s hard to know in advance how well players are going to be able to exploit the options you give them. Despite their efforts, different classes end up “overpowered,” or “OP” in gamer lingo. Or “underpowered,” for which the slang isn’t always printable.

Diversity is the glory of the universe. Nature abounds in variety. Its glories are displayed in a variegation without variance. This variety presents us with beauties that inspire human minds with transports. Beauties which could never flow from one object, or one species of beings, though exactly the same in their proportions and powers.

In patch updates, the rules get tweaked to try to balance it all. OP classes are reduced in power, or “nerfed” (imagine having your air rifle taken away and replaced by a Nerf gun that shoots foam projectiles because you were doing too much damage). Underpowered classes are “buffed” (nobody remembers whether the metaphor was originally “given muscles” or “polished until they shine”).

In this case, Blizzard had gotten feedback from players that “warlocks are OP and need to be nerfed.” So the patch made some of the spells a warlock can cast a little weaker.

Nerfing, the word and concept, is super common among gamer and adjacent communities, to the point where the feedback “[x] is OP and needs to be nerfed” is a meme of its own. I’ve chosen this specific example, the Great Warlock Nerfing of 2009, because a certain inventor and billionaire philanthropist from Canada says it’s what inspired him to try to change the world. And he may not be entirely joking.1

I’ll explain. First, though, as is my way, we’re going to talk about Ancient Greece.

ΩΠ and needs to be ostracized

What is current Reason in one kingdom loses its currency in another.

The Athenian democracy had a more democratic nerfing process than Blizzard’s. Once a year, citizens had the option of voting to exile one of their own for ten years. The votes were cast anonymously using shards of broken pottery, so the practice came to be known as ostrakismos, from the word for pottery.

We don’t think they did this a lot, maybe fewer than twenty times. There was an annual vote on whether to ostracize anyone, and it usually failed. When it passed, then after two months of campaigning, the vote on whom to ostracize was held. Anyone was eligible, so it was all via write-in ballots. Scribes were available to help the illiterate.

The highest vote-getter was then immediately banished with no further discussion. Because you didn’t need to be convicted of any particular crime, there wasn’t much of a stigma to ostracism. As long as you stayed away for ten years, you were welcome to return, and many did.

Ostracism, in fact, was something of a mark of distinction. It meant you were famous enough to be infamous, and also ethical enough that ostracism was the only legal censure available. The most common reason to be ostracized was that you were the leader of the second-largest political faction. But there were plenty of other reasons. We know this in part because voters had the option of adding a note explaining their vote, scratched on the same pottery shard, and if there’s one thing archaeologists are good at, it’s digging up pottery shards.

The original idea was to avert tyranny. If one citizen was starting to get too powerful, it was a threat to democracy. Politicians went along with this, probably because it was a gentler alternative to assassination or show trials. Later, people would be ostracized for being too ostentatiously wealthy, or too ostentatiously virtuous. A musicologist was ostracized for having too many powerful friends. For some reason, having a literal big name, as in a name that meant big, seems to have been correlated. The last person to be ostracized was named Hyperbolus, and I think the only one known to get a substantial amount of votes twice was named Megacles.

The ten-year exile forced the community to adapt to the absence of a prominent member. If the ostracized returned afterwards, they’d find they didn’t have as much responsibility, and therefore less power. They’d been nerfed.

(There was a safety mechanism to undo the ostracism if it turned out that oops we really do need this person. This was used a couple of times, for example when they exiled their best general and then got invaded.)

OP and needs to be decentralized

And I think 'tis not an unfair proposal that those who are so forward to think for us should subscribe this condition: that if we are found wrong another day they’ll be content to suffer in our stead, for surely the leader who sees and not the follower that sees not deserves all the hazard of a Fall into the Ditch.

Vitalik Buterin woke up one morning to find his favorite spell taken away by the true rulers of the World of Warcraft, elder gods whose power could not be contained by any quest. This was approximately the smallest amount of oppression one person could possibly experience, but it still stung. The game encourages you to think of your character as yours, as self-expression, and to think of the world as being built jointly by all of its players, as in real life. Blizzard’s patch broke the illusion for him.

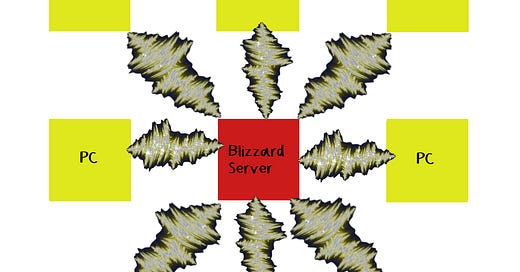

He came to think of it as a parable about centralized services. Any instance of World of Warcraft is run by many different computers working together, but they’re not all equally important.

When you play WoW, your computer is interacting with many others, but it’s all mediated by, and dependent on, one computer in particular, a server controlled by the makers of the game. If that server breaks, or its owners decide to shut it down or change the rules, there’s no way for the rest of the “network” to adapt. It’s a single point of failure.

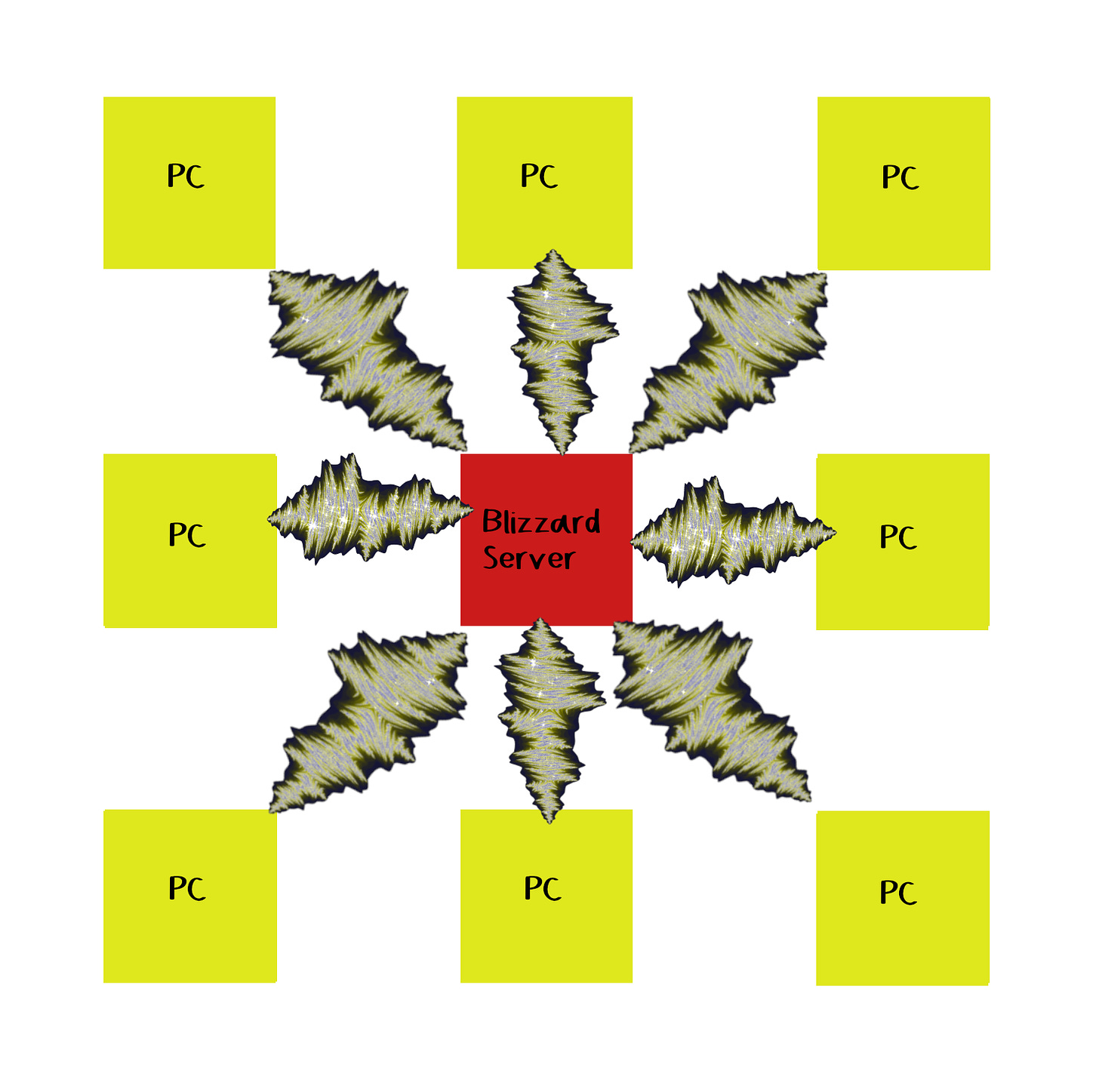

What if, instead, WoW worked like this?

Here, we’ve rewired the magic so that every PC is connected to the network by at least two sparkly glow bolts. That means that if any one PC starts misbehaving, the network can just start ignoring it without falling apart. This is a peer-to-peer architecture—there’s nothing super special about the PC in the center, it just happens to be more connected at the moment.

Decentralization is easier drawn than done. I guesstimate that half of the things we do over the internet look more like the first diagram than the second. Everybody who reads this post on Substack is downloading it from the same place2. But the system that tells your computer where that place is is peer-to-peer. If you’re reading this in your email, you’ve gotten it through a hybrid system, a peer-to-peer federation of centralized mail servers.

This is why a bad software update recently took out a good chunk of the internet, but not any systems that run solely on diverse, decentralized hardware. Some people found that they couldn’t call 911, but they could send an email. If a system had any essential component that was running only on certain kinds of Windows computers, it was down. If no part of it was centralized in a broken server, it was up.

Here’s a big part of why we still serve files from centralized servers: that way, we get to charge for them. Peer-to-peer file-sharing systems (e.g. BitTorrent) immediately became associated with piracy. Charging people money in a peer-to-peer setup is super tricky. Who’s in charge of saying whether the payment actually went through?

The correct answer to that question, Buterin thought, was “everybody.” To have robust decentralized systems, you need robust decentralized finances. So he started studying cryptocurrency.

OP and needs to be made obsolete

A man’s conscience may be drawn to any length, but his money can’t.

Bitcoin, the predominant cryptocurrency, is popular because of a first mover advantage, not because it’s particularly good in comparison to its rivals. It shows all the signs of a common tech pitfall—what was meant to be the prototype accidentally became the product.

Buterin invented an alternative, Ethereum. (To my knowledge, I don’t own or have financial interest in any Ether, so I’m going to praise it unabashedly.) Ethereum’s two core improvements over Bitcoin were its smart contracts, designed to serve as infrastructure for all sorts of new decentralized institutions, and a greater ability to evolve, both for technical reasons and because of the culture of its early adopters. This evolution allowed it to cut its energy usage by 99% in 2022. So, good news! NFTs aren’t killing the environment anymore! Increasingly, all the innovations in decentralization are using the much-more-energy-efficient model Ethereum championed.

This is the ideal way to dislodge something harmful or inadequate—make an alternative that’s not just better, but better enough to outweigh its first mover advantage. You also generally need to advocate for your alternative well enough to outweigh its branding disadvantage.

Original Poster needs to be nerfed

…and so much branded by summer birds, who have only one note in doctrines, in worship, in discipline, in conscience, and have cropped men's ears because they could not pronounce Shibboleth with their tongue.

OP, in slang, can also mean “original poster,” as in the first to comment in a given thread. Websites often try to nerf the undue prominence of the original poster—Hacker News grays their text out, online newspapers show comments in reverse chronological order, and other sites let community moderation vote new comments to the top.

In a roundabout way, I’m writing about nerfing today because I read this from Naomi Kanakia:

The Great Books, as a brand or an ethos, are the canon, the idea that we all need to read the same books so that we all understand each other, and these should be the great classics because then we also get to understand the people of the past who read those books too.

The first take that popped into my head was, verbatim, “the Great Books are OP and need to be nerfed.” Generalize the "Read another book" meme of 2016, complaining that everybody was using Harry Potter metaphors. Rather than saying “and therefore it should be required reading in schools,” it became fashionable to say “and therefore we need to diversify.” Which has a certain logic to it—if we had more commonly-used imagery, we could use more apt metaphors, rather than straining to compare every terrible authority figure to Dolores Umbridge. The same is true for many of the books in the Western canon—Shakespeare said a lot, but he didn’t say everything. Not every romance is Romeo and Juliet.

I thought better of this idea and wrote Fighting Over A Dead Microphone instead, because I just don’t think anybody, from college board to social influencer, has the ability to steer, so what’s the point? But if I pretend for a moment to be a dictator, the concept does still have a certain perverse appeal. Every 10 years or so, determine what the most-commonly-assigned books across the country are, and ban them from required reading lists until the next cycle. Give the second-tier books that big break they’ve been waiting for. Would it kill us to have a few people around who read Marlowe before Shakespeare?

Or, hey, go more obscure. I’ve been enjoying wandering around in the older English-language books digitized by Google. I think Harmony Without Uniformity, an anonymous 1740 polemic against religious uniformity, meets all of the standard prerequisites for a Great Book except one: nobody’s read it3. Including me, until a few hours ago. It’s a window into some of the central conflicts of the era, ones still relevant today, anticipates some modern ideas, and is well-written, at least by the standards of the time and genre. Including it would also help with the tension Kanakia writes about: she notes that we’ve started to treat “world literature” as a required element of any canon, but that part of the point of having a canon is that the works are supposed to be connected. Just dropping in Eastern-tradition works, without also including Western works written in dialogue with them, doesn’t form an alloy. Harmony Without Uniformity shows clear signs of Eastern ties—for example, the book’s title is probably a translation of a phrase from Confucius.

Books like these are victims of a first-mover advantage in the curation of philosophy—people chose to anthologize Hume rather than a collection of anonymous authors, and then future generations had to read Hume too so they could understand what the previous one was talking about. Hume is perfectly fine, but if you plucked him out of the Great Books there’d still be plenty of Humean thought left in.

(All the pull quotes in this article are from Harmony. Just in case you didn’t recognize them—maybe your education neglected the classics.)

Self-ostracism

Their dominion is extended over many provinces, obeyed and admired everywhere, and yet they can neither see with other people’s eyes nor hear with other people’s ears.

Aristides, ostracized in part because his reputation was too positive, claimed later to have agreed and voted for himself. Buterin has been known to take similar steps. He worries about becoming a single point of failure himself, for the cryptocurrency community. People started calling him a “philosopher-king,” a reference to the kind of tyranny Plato called for and ostracism was designed to avert.

So he doesn’t do much self-promotion, and goes through long periods where he declines all interviews. If you haven’t heard of him, it’s because he wanted it that way. He still contributes research to the field, but says he hopes the community will be resilient enough not to miss him when he stops. His philanthropy, taking place via public transaction records in blockchains, isn’t hidden, but also isn’t trumpeted.

(I doubt he’d mind me writing this article, though. He’s not that reclusive.)

Every billionaire is a potential solution to a policy failure.

Are not inventions in the human system imitations of nature? Yea, what are arts but improvements of nature in its multiformity?

Vitalik Buterin’s donations tend to be toward worthy causes that, for one reason or another, aren’t attractive targets for government grants. He donated to AI safety orgs before it was cool (and not after). He donates to non-profits tasteless enough to brand themselves as trying to “cure aging,” rather than “do research to improve medical care for the elderly.” He’s trying to donate a billion dollars to COVID relief in India.

And he’s sending aid to Ukraine in its war against his birth country. Aid that won’t stop no matter who wins this year’s Presidential election.

Billionaires are an inefficient and dangerous centralization of wealth. But the solution probably isn’t “tax them and use the money to fill deficits in the federal budget.” (Canadian government, in Buterin’s case.) That’s in some ways a worse centralization—it turns the executive into a single point of failure.

One compelling example of the societal value of billionaires is contraception research and distribution. Governments don’t like to fund it, because sex, so when it can’t be immediately monetized it often relies on rich, public-minded patrons. Katharine McCormick, a women’s rights activist who inherited a fortune in 1947, used the money4 to fund the invention of the contraception pill, basically singlehandedly. And today, the Gates Foundation is bringing contraception to countries whose leaders disapprove.

So the government funds the stuff the majority likes, and then a handful of billionaires fund whatever they feel like. How can we improve on this system? Buterin, unsurprisingly, has some ideas. His 2019 paper, A Flexible Design for Funding Public Goods, extends the concept of quadratic voting to “quadratic funding.5” The system is designed to allow for people with different policy interests to come to an honest and optimal consensus on how to spend their money…no matter how their wealth is distributed. People with more money to give still have a bigger say, but in this system, unlike our current system of private funding, the majority gets a say too.

Billionaires are OP and need to be nerfed…and it just might be billionaires who figure out how.

In Conclusion

Both the first and last section of an article are OP, according to research into serial-position effects on how well people remember different parts. Anything I write here is going to hold more weight than the middle bit about the Great Books. Best to make it a call to action.

If there’s not enough of a thing to go around, make there be more of that thing. If the system is too centralized to allow that, first change the system. That’s the essence of both anarchism and systems engineering. Recognize the value of individuals, but be resilient enough that no one person is essential. Celebrate your heroes, and nerf them too.

If nothing else, it pushed him to quit World of Warcraft. Quitting WoW does wonders for your productivity.

More or less. There are various tricks to add scale and redundancy to even a centralized architecture, although they tend to add new points of failure.

Also, it’s a bit short and one-note, so you’d probably want to anthologize it with other books by anonymous or obscure authors from the early 1700s.

Or the 15% of it she had left after taxes.

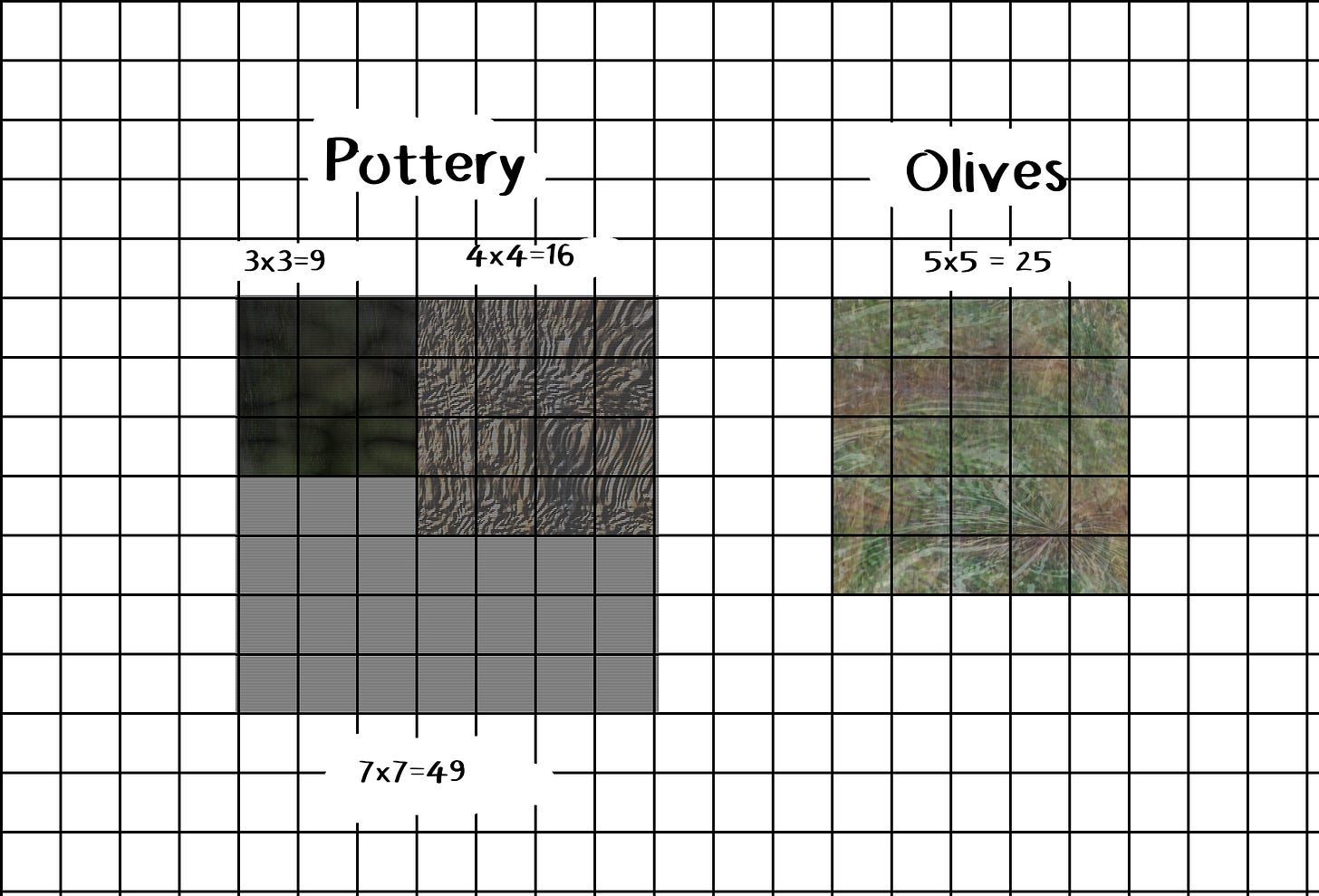

Ancient Athens had the key mathematical concept behind this, but didn’t think to apply it to voting. To put it how they might’ve, in quadratic funding, each donor lays out the money they’ve contributed in the shape of a square. People who agree on what to fund put their squares next to each other, creating uneven shapes. Then, all the money is redistributed to make all the shapes into squares again. For example, say two people contribute $9 and $16, respectively, to subsidizing pottery, and one richer donor, whose name is probably Megaplautus or something, contributes $25, the same as them both put together, to subsidize olives. Under quadratic funding, we make the three donations into 3*3, 4*4, and 5*5 squares, and put the two smaller squares next to each other, creating a shape whose longest side is $7 long. If we filled it out into a square, it would be about double the size of Megaplautus’s square (49 to 25). So about twice as much money ends up going to pottery, which two people wanted, as to olives, which one richer person wanted. We have to scale it to the total amount that’s been pooled, $50, so it ends up as $33 and $17.

If they were just donating independently, an equal amount would go to both, while if they were using a democratic winner-take-all system, it’d all go to pottery. Under certain assumptions, this specific intermediate system maximizes overall satisfaction.