The Cosmic Pioneer: Selected Poems By Sam Walter Foss

Bio

Sam Walter Foss (1858 – 1911) was a New England poet and librarian. He wrote simple, accessible poems about Americana and the common man. Many of his poems express, in various ways, wisdom about the tradeoff between exploration and exploitation, the dilemma we all constantly face between trying something new and enjoying what you have. He was seen as universally kind-hearted, and said proudly that he had never received any hate mail.

The Calf-Path

I.

One day through the primeval wood

A calf walked home as good calves should;

But made a trail all bent askew,

A crooked trail as all calves do.

Since then three hundred years have fled,

And I infer the calf is dead.

II.

But still he left behind his trail,

And thereby hangs my moral tale.

The trail was taken up next day,

By a lone dog that passed that way;

And then a wise bell-wether sheep

Pursued the trail o'er vale and steep,

And drew the flock behind him, too,

As good bell-wethers always do.

And from that day, o'er hill and glade.

Through those old woods a path was made.

III.

And many men wound in and out,

And dodged, and turned, and bent about,

And uttered words of righteous wrath,

Because 'twas such a crooked path;

But still they followed—do not laugh—

The first migrations of that calf,

And through this winding wood-way stalked

Because he wobbled when he walked.

IV.

This forest path became a lane,

that bent and turned and turned again;

This crooked lane became a road,

Where many a poor horse with his load

Toiled on beneath the burning sun,

And traveled some three miles in one.

And thus a century and a half

They trod the footsteps of that calf.

V.

The years passed on in swiftness fleet,

The road became a village street;

And this, before men were aware,

A city's crowded thoroughfare.

And soon the central street was this

Of a renowned metropolis;

And men two centuries and a half,

Trod in the footsteps of that calf.

VI.

Each day a hundred thousand rout

Followed the zigzag calf about

And o'er his crooked journey went

The traffic of a continent.

A Hundred thousand men were led,

By one calf near three centuries dead.

They followed still his crooked way,

And lost one hundred years a day;

For thus such reverence is lent,

To well established precedent.

VII.

A moral lesson this might teach

Were I ordained and called to preach;

For men are prone to go it blind

Along the calf-paths of the mind,

And work away from sun to sun,

To do what other men have done.

They follow in the beaten track,

And out and in, and forth and back,

And still their devious course pursue,

To keep the path that others do.

They keep the path a sacred groove,

Along which all their lives they move.

But how the wise old wood gods laugh,

Who saw the first primeval calf.

Ah, many things this tale might teach—

But I am not ordained to preach.

Commentary

The central metaphor in The Calf-Path is a common one— unconventional thinkers are “off the beaten path” and, they hope, “trailblazers.” What Foss brings to it is an inversion of dignity.

If someone is “off the beaten path,” that might just be a charitable way of saying they’re lost. People off the beaten path move slower. They get hit in the face by tree branches and get their boots stuck in mud. They may or may not be doing something worthwhile, but they look silly. People on the path don’t look like anything in particular.

But in The Calf-Path, we strip the dignity away from the path-followers. They’re not necessarily moving faster—they might be making a mistake in following the winding path instead of cutting through. When it’s not a mistake, when you’re not able to blaze your own trail, you’re still following behind the original trailblazer, someone who barely knew how to walk.

Robert Frost’s The Road Not Taken was written decades later and follows in Foss’s footsteps, poking gentle fun at someone agonizing at a fork in a path in the woods, when “the passing there had worn them really about the same.” This next poem from Foss can be read1 as a response to Frost’s “Oh, I kept the first for another day! Yet knowing how way leads on to way, I doubted if I should ever come back.”

I Shall Not Pass This Way Again

"I shall not pass this way again. " - WILLIAM PENN.

Right words and shrewd, good William Penn,

I shall not pass this way again.

My long way and the winding track

Which I pursue will bend not back.

Mayhap it stretches very far,

Mayhap it winds from star to star;

Mayhap through worlds as yet unformed

Its never-ending journey runs,

Through worlds that now are whirling wraiths

Of formless mists between the suns.

I go beyond my widest ken

But shall not pass this way again.

So, as I go and cannot stay

And never more shall pass this way,

I hope to sow the way with deeds

Whose seed shall bloom like May-time meads,

And flood my onward path with words

That thrill the day like singing birds

That other travellers following on

May find a gleam and not a gloom,

May find their path a pleasant way,

A trail of music and of bloom.

Strew gladness on the paths of men —

You will not pass this way again.

Commentary

William Penn probably never said that, and I don’t know who first did. Foss is using it in a similar spirit as whoever invented that line—the next sentence is usually given as something like “If there’s any kindness I can show, let me do it now.” What distinguishes Foss’s message here, as often happens in his work, is a daring sense of hope. Foss dreams bigger, both for the speaker and his deeds. Where “Penn” is acknowledging his own mortality, the fleeting nature of his life and therefore his opportunity to do good, Foss leaves room for the possibility of spiritual or material transcendence. He will not pass this way again, perhaps, because he’ll be on his way to a distant star that’s still coalescing. And Foss admits to a hope I’m sure Penn secretly had—not only good deeds in the moment, but an enduring legacy.

It wasn’t William Penn’s idea to name it Pennsylvania. He wanted his colony to be named Sylvania, from the Latin for “forest,” recognizing his own journey through the woods. The king added the Penn and refused to remove it. But William Penn would have been justified in any secret hopes he harbored, no matter how grand, for the seeds he planted along his path. Scott Alexander writes:

It occurs to me that William Penn might be literally the single most successful person in history. He started out as a minor noble following a religious sect that everybody despised and managed to export its principles to Pennsylvania where they flourished and multiplied. Pennsylvania then managed to export its principles to the United States, and the United States exported them to the world. I’m not sure how much of the suspiciously Quaker character of modern society is a direct result of William Penn, but he was in one heck of a right place at one heck of a right time.

O'Meara's Cosmic Pioneer

Born to re-animate his era

Was young Erastus Jones O'Meara ;

For this young hero of my verse

Was born to search the universe,

To sail through the unbounded skies

And all the cosmos scrutinize ;

To sail through cosmos to the reign

Of chaos, and sail back again.

It was his cherished hope to rise

A great Columbus of the skies,

To sail through ether's star-isled seas

As sailed the mighty Genoese,

And earn a name beyond compare

As the great admiral of the air.

He hoped to float off on the breeze

Through those unsailed aërial seas,

And find new Indies and new races

Out in the interstellar spaces.

As old times gave Magellan birth

To circle the ungirdled earth,

So had this late transcendent era

Brought forth Erastus Jones O'Meara,

The hero of this halting verse,

To girdle the wide universe ;

And 'twas the end of his emprise

The cosmos to Magellanize.

Before he launched forth all alone

Into the limitless unknown,

'Twas indispensable, I ween,

To make a first-class flying-machine.

And he's the greatest of his race.

The climax of consummate brain,

Who'll build a ship to sail through space

And then sail back again.

But this Erastus Jones O'Meara,

The topmost flowerage of his era, —

This feat, from all past ages hid,

Erastus Jones O'Meara did.

And so he made a flying-machine,

The best the world had ever seen :

Its levers worked with perfect ease,

Its pistons did not grind or wheeze,

Its belts all moved without constriction,

Its cog-wheels whirled and made no friction,

Its broad wings flapped with graceful swing

When young Erastus pulled the string

They moved with grace so grand and regal

That they improved upon the eagle.

"When it gets in the air up yonder, "

Erastus said, "'twill beat the condor,

And sail as grandly through the skies

As any bird of paradise;

Yes, sail the seas of space across,

An interstellar albatross!"

And then he painted large and clear

In words that he considered terse,

"O'MEARA'S COSMIC PIONEER

AND SEARCHER OF THE UNIVERSE."

So, when this great machine was done,

'Twas made to sail beyond the sun.

Between all parts of this creation

There was a mutual adaptation,

A harmony of part and whole

That made it like a living soul:

Perfect in piston, belt, and line,

A unity of grand design.

No blemish had this flying-machine,

No fault that any man could spy,

Except this single fault, I ween, -

No living man could make it fly.

"But that's all right," he said. "You'll own

No flying-machine has ever flown;

And my machine has stood the test

And turned out good as all the rest.

A man's abilities are high

Who'll cause a flying-machine to fly.

And mine will do it, I declare,

When I have fixed that pedal there,

And filed that cog-wheel down a mite,

And screwed that middle screw in tight;

And early next week I shall fly,

Start in and navigate the sky. "

He fixed his pedal, screwed his screw,

His cog-wheel filed, and tried anew ;

The wings they flapped with perfect poise,

And worked without superfluous noise.

They bravely reached up toward the sky,

And looked as if they ought to fly;

They looked as if they ought to climb

The great translunar heights sublime,

And make a wide extended flight

Out into "chaos and old night. "

But truth the poet must revere,

And I must brutally assert,

"O'Meara's Cosmic Pioneer"

Stayed stationary in the dirt;

Still in the dust and dirt it stayed

In the old wood-shed where 'twas made.

O'Meara worked from day to day

Till his brown hair had turned to gray ;

And with life's leaf no longer green

He tinkered on his old machine ;

Impelled by his undying hope,

He fixed a cord or trained a rope,

Or loosed a belt, or shaved a beam,

And lived his life and dreamed his dream ;

And then he died, as all men die ;

That's all—he never learned to fly.

That's all ? Ah, no ! for all life's scenes,

Filled with unflying flying - machines,

Attest that all men everywhere

Are navigators of the air ;

We all make fair machines to rise

To sunset islands of the skies,

Through oceans without rocks or bars,

Whose archipelagoes are stars ;

And all good men until they die

Make flying-machines that will not fly.

And shall our flower of hope contract

And freeze in these cold winds of fact :

That the round sky is very high,

And flying-machines can never fly?

No, woe to him who has no gleam

From the bright starlight of a dream,

Who never sees the stars draw nigh,

And never dreams that he can fly !

So hammer on in hope serene,

And never falter till you die ;

Some day there'll be a flying-machine

That in reality will fly.

Commentary

Foss published O'Meara's Cosmic Pioneer in 1897. Six years later, the Wrights built their flying-machine that flew. The bard of optimism had lived long enough to see the archetypal unattainable dream become reality. In The Library Alcove, his column in the Christian Science Monitor, Foss celebrated the way that air-flight, like Halley’s Comet, was invigorating people’s curiosity.

The librarian can take a big share of the work in transmuting vision into fact. Thousands of men everywhere are thinking about air-flight. Hundreds in an amateur way are experimenting. All articles about the subject in review and books are eagerly read. Here is a chance for the librarian to help to push the world along. The aeroplane is going to be something more than a pleasure vehicle, a conveyance for an afternoon’s outing. It is going to be a world-transformer.

So the librarian that gets people to reading and thinking about aeroplanes, man-flight and aerial navigation is working in harmony with the Zeitgeist, the Spirit of the Age, and does more, probably, than he imagines to help the progress of the world.

One of the patrons of the Somerville Public Library, while Foss was the head librarian there, would likely have been Joseph Gavin, a Somerville resident who had to drop out of school circa 1910 in order to support his family. Gavin, who eventually went into newspaper advertising, was one of those lay people fascinated by aviation. In 1927, he took his 7-year-old son to see Charles Lindbergh land his plane. Joseph Gavin Jr. remembers:

“We got within 15 feet of Lindbergh, and about the same distance from his airplane. From that point on, flying machines were my interest—doesn’t matter if it’s airborne or in orbit.

…

I was pretty sure I wanted to be an engineer … and do something with flying machines.”

He did. He headed the project that built the Lunar Module of the Apollo Program. His father lived to see his son’s invention put men on the moon, and return them safely. Foss had helped “to push the world along” in exactly the way he was trying to.

The Wright flyer was built by characters straight out of some of his poems: three siblings from Dayton, Ohio who’d each taken different paths, then reunited. Wilbur stayed home, took care of his parents, and read and tinkered in his spare time. Orville dropped out of high school and started his own printing business with a homemade printing press. Katharine went to college and became a teacher (but mostly kept to a simple “homespun” style of speech and writing, which would have delighted Foss). The three developed different skills that, in combination, allowed them to succeed where the fictional O'Meara, “greatest of his race,” had failed.

And pioneers usually do fail. When he writes

But truth the poet must revere,

And I must brutally assert,

"O'Meara's Cosmic Pioneer"

Stayed stationary in the dirt;

Foss was expressing a principle he stuck to in his work. In his story-poems, people who do the bold, risky thing usually fail, while people who stay home on the farm usually thrive.

Wearing His Dad’s Ol’ Clothes

"Yes, I," said Jim, "shall leave this hole -

No place for men of talent here.

I don't propose to squeeze my soul

Down into such a narrow sphere ;

And I propose to make my pile,

A good round fortune, fair and square,

And after I shall once strike ile,

I'll grow into a millionaire.

Now, brother Tom, where will you roam?

And what great work do you propose?"

"Well I," said Tom, "will stay to home,

And wear my dad's ol' clo'es."

"Now I," said Sam, "don't care for wealth;

A banker's life is far too tame;

But, bless me ! if I have my health

I'll clamber up the heights of fame.

Our statesmen are degenerate,

A poor, debilitated crew;

But I propose to take the state,

And renovate it through and through;

To rule as Cæsar did in Rome,

That is the end that I propose."

"Well, I, " said Tom, "will stay to home,

And wear my dad's ol' clo'es."

"Now I," said Bill, "propose to rear

A name to permanently endure,

And gain my province square and clear

Within the realm of literature.

Just look at Shakespeare now, and note

How greatly grand he looms, and tall,

And just because he simply wrote

A lot of writings -that is all.

And so to write a mighty tome

Of thought, like him, do I propose."

"Well I," said Tom, "will stay to home,

And wear my dad's ol' clo'es."

Jim went away, and started fair,

With courage strong and almost rash,

To make a mighty millionaire;

But then he couldn't collect the cash.

And Sam had been a statesman grand,

And ruled where'er our banner floats -

He would have been, you understand,

But then he couldn't secure the votes.

With votes and cash they might have clomb

To heights of wealth and fame, who knows ?

But Tom just simply stayed at home,

And wore his dad's ol' clo'es.

And Bill, he might have written thoughts

To make old Shakespeare's pale and sink,

And doubtless would have written lots

If he'd had any thoughts to think.

So Jim and Sam and Bill came back

To their old home, a wan and thin,

A ragged, hungry-looking pack;

And well-fed Tom, he let 'em in.

And now all three no longer roam ;

They live on Tom in sweet repose.

All three contented stay at home,

And all wear Tom's ol' clo'es.

Commentary

It’s easy to misread Wearing His Dad’s Ol’ Clothes as an “Ant and the Grasshopper” style fable—Tom’s the wise one, his brothers are foolish. It is a fable, but that’s not the moral. We’re here to praise Tom’s humility and loyalty, but not to condemn his brothers for misjudging their own potential. Somebody should try to fly, and somebody should be there to catch them when they fall. Foss reminds us not to feel contempt for the Toms of the world—and not to feel contempt for ourselves, when we make an unambitious choice.

Wilbur Wright himself, the brother who stayed home, felt some self-loathing over his lack of ambition. Every move he made felt like a retreat. Even when he and Orville decided to abandon their bicycle business to focus on flight, Wilbur wrote that they were only doing it because local competition had arisen in the bicycle business, and they lacked the aggression and drive to compete. Out of meekness, they’d fled the beaten path.

Fortunately, their sister Katharine didn’t inherit the Wright meekness gene, enabling her to fund, manage, and then promote their new business. It takes all sorts.

On this wide planet there is room

For men of opposite creed ;

There's room for Mr. Justin Bloom

And Mr. Gontoseed.

For both these mortals there is need,

For both there's ample room,

Though Justin Bloom hates Gontoseed,

And Gontoseed hates Bloom .

" Out from the dead past's darkened gloom

I march to break of day ;

I face the sun," says Justin Bloom,

"Tap drums, and march away ! "

"The wisdom of the ancient days

Serves all my spirit's need;

I keep the good old precious ways,"

Says Mr. Gontoseed.

And Justin Bloom, if left alone,

Would set the world on fire;

And Gontoseed, and all his breed,

Would stagnate in the mire.

While one would plunge in the abyss,

One saunter on the grass,

One holds back from the precipice,

One leaps the wide morass.

Though one is full of rest and sleep,

And one is full of noise,

They both together work to keep

The world in equipoise.

On this wide planet there is room

For both; and both we need.

Three cheers, three cheers for Justin Bloom!

Three cheers for Gontoseed!

Commentary

Justin Bloom and Gontoseed, terrible pun and all, is a tidy little key to understanding Foss’s aims and worldview. It’d be superfluous to comment much on the message. You get it. Foss doesn’t obfuscate. He’s a librarian—he’s not going to disguise the information you want in cryptic riddles. He doesn’t pretend that he’s writing about two flowers, or an old man and a young one, or any two specific people.

Foss is only challenging when he writes entire poems in phonetic dialect (An' w'en ol ' Cy he came to die/He sez, "W'en I am gone,/I wish to travel to the sky/With my ol' trowsis on."). You won’t find any of those here because they annoy me.

Foss is establishing a spectrum here, with two men of “opposite creeds” at the poles. He clearly falls somewhere in the middle, as he asserts that the two hate each other, but he loves them both. In his most well-known poem, he positions himself more precisely.

The House By The Side Of The Road

There are hermit souls that live withdrawn

In the place of their self-content;

There are souls like stars, that dwell apart,

In a fellowless firmament;

There are pioneer souls that blaze the paths

Where highways never ran-

But let me live by the side of the road

And be a friend to man.

Let me live in a house by the side of the road

Where the race of men go by-

The men who are good and the men who are bad,

As good and as bad as I.

I would not sit in the scorner's seat

Nor hurl the cynic's ban-

Let me live in a house by the side of the road

And be a friend to man.

I see from my house by the side of the road

By the side of the highway of life,

The men who press with the ardor of hope,

The men who are faint with the strife,

But I turn not away from their smiles and tears,

Both parts of an infinite plan-

Let me live in a house by the side of the road

And be a friend to man.

I know there are brook-gladdened meadows ahead,

And mountains of wearisome height;

That the road passes on through the long afternoon

And stretches away to the night.

And still I rejoice when the travelers rejoice

And weep with the strangers that moan,

Nor live in my house by the side of the road

Like a man who dwells alone.

Let me live in my house by the side of the road,

Where the race of men go by-

They are good, they are bad, they are weak, they are strong,

Wise, foolish - so am I.

Then why should I sit in the scorner's seat,

Or hurl the cynic's ban?

Let me live in my house by the side of the road

And be a friend to man.

Commentary

Not all of Foss’s first-person poems are autobiographical, but The House By The Side Of The Road must be. He’s neither an explorer nor a monk. He stays in one place, writing what he knows, the only way he knows to write it. But that place is chosen to let him connect to the travelers, the pioneers, and to everyone else—because everyone is worthy of compassion and has something to teach.

This poem was one of the most popular pieces of pop culture in his time. It inspired a radio show, catchphrases, and was supposedly embroidered more often even than “Home Sweet Home.”

Fixing The Old Thing Right

Said Adam unto Seth, his son,

"My boy, my life is nearly done ;

I am the first man ever made,

And yet a failure, I'm afraid.

And you, my boy, must bring to men

Your father's Eden back again.

You must correct our great mistake,

Our foolish blunder with the snake.

The world has wandered from the light ;

Go in and fix the old thing right. "

Said Seth to Enos, his first born,

"My boy, your life is in its morn ;

You've scarcely passed from boyhood's stage,

You're but four hundred years of age.

I've struggled on through hopes and fears,

And lived above five hundred years ;

And now I feel that there can be

But a few centuries more for me.

I've tried my prettiest since my birth

To steer and regulate the earth ;

But all of Nature's plan, I fear,

Is pretty badly out of gear.

So, while I travel toward the night,

Go in and fix the old thing right. "

Said Enos unto Cainan, “ Lad,

I fear the world is growing bad.

But when I see before me spread

Your large development of head,

And know you deem all wisdom shut

And focussed in your occiput,

I feel that here is one at last

Who should redeem the wretched past ;

And so I say, take up the fight,

Go in and fix the old thing right. "

Said Cainan to Mahalaleel,

"The envious years upon me steal,

And now I feel as old and dried

As father Enos when he died.

Though I possessed, as father said,

A large development of head,

The world would ' haw ' when I said ' gee, '

And ' gee ' when I said ' haw.' Ah, me !

I've tried for these nine hundred years

To drive this balky yoke of steers ;

And now I pass the goad to you,

To do the best that you can do.

And when old Cainan fades from sight,

Go in and fix the old thing right. "

Mahalaleel to Jared said,

My son, 'tis time that I were dead ;

And in this view of mine, I guess,

You too have come to acquiesce.

The world has reached a sorry plight;"

Go in and fix the old thing right."

So Jared, when his life was done,

The same to Enoch talked, his son.

And Enoch, like a faithful pa,

The same to young Methuselah,

Who near a thousand years of strife

Mourned o'er the brevity of life,

And said to Lamech, "Life is short,

And very little I have wrought,

Though I might make the world sublime

And perfect, if I had the time.

But in my life's contracted span

I have but merely just began;

No earthly power my life can save,

I seek my premature grave.

My son, take up the unfinished fight;

Go in and fix the old thing right."

Soon Lamech left the world to Noah,

Just as his fathers had before.

And then the Flood came on to rout

And drown the whole Creation out;

Though all had tried with main and might,

They failed to fix the old thing right.

But when a man is born to-day,

He starts out in the good old way,

And bravely works from dawn till night,

To try to fix the old thing right.

The same old lightning in the blood

That thrilled men's hearts before the Flood,

Drives all men to the endless fight,

To try and fix the old thing right.

And though the clouds of doubt draw nigh,

And shut the sun from out the sky,

And though life marches through the gloom

To music of the steps of doom,

A voice comes through the darkness far,

And smites the cloud-wrack like a star,

And makes its thunder-blackness bright,

"Go in and fix the old thing right."

Commentary

If The House By The Side Of The Road is Foss at his most Christian, this one is one of his most Jewish. Fixing The Old Thing Right uses the same core metaphor as tikkun olam. It also echoes a more esoteric teaching that there’s one potential messiah in every generation, following a Biblical lineage. I don’t think this is conscious reference.

The world is broken.

Every new generation builds on the work of the last.

Anyone who has both of these contradictory intuitions, and tries to reconcile them, will reach some version of tikkun olam.

Himselfing

WHEN Shakespeare was shakespearing, he knew not

he shakespeared,

And Meyerbeer meyerbeering knew not he meyer-beered,

Thucydides thucydidesing,

Demosthenes demosthenesing

Did their own work in their own way and did it as

they pleased,

But knew not they thucydidized or they demosthenesed.

When Chaucer was a-chaucering, he chaucered on unknowing,

And Edgar Allan Poe poed on and knew not he was poeing ;

Unconscious Poe poed poingly,

And Shelley shelled unknowingly,

And Kant he kanted all his life and knew not he

could kant ;

And Dante danted evermore but knew not he could

dant.

When a man is socratesing you may know he's Socrates,

And a man themistoclesing he must be Themistocles ;

By the way a man's behaving

Be he neroing or gustaving,

He is Nero or Gustavus and no other man can be,

For no other man can do his job - no other man

than he.

So let Briggs keep on a-briggsing, and Smith keep

smithing on,

And Griggs keep on a-griggsing, nor Johnson cease

to john ;

Magoun keep on magouning,

And Spooner keep a-spooning,

And Bagster bag, and Jacobs jake, and Logan always

loge,

And Rider ride, and Snyder snide, and Hogan always

hoge.

Let Stubbs keep on a-stubbing but try not to shake-

speare,

And Grubb continue grubbing nor try to meyerbeer;

Let Streeter keep a-streetering,

And Peters keep a-petering ;

For in somebody-elsing there is no fame or pelf,

Let each man go himselfing and each man be himself.

Commentary

This one is probably too widely-shared a sentiment for me to claim it in the name of Judaism, but it sure does bring to mind the Rabbi Zusya story—“When I die,” Rabbi Zusya said, “if God were to ask me why I wasn’t more like Maimonides, I’d have plenty of answers. I wasn’t born with the right talents, nor in the right time and place, to be Maimonides. But He won’t ask me that. He’ll ask me why I wasn’t more like Zusya, and what excuse could I give then?”

The Half-Man and the Whole-Man

(Read at the Woman Suffrage festival.)

No carpenter can build a man the way he saws a shelf ;

The wisest way to make a man is - let him make himself.

The way to build a giant, and the surest way I know,

Is to drop him in the sunshine with this one commandment, "Grow !"

The way to make a perfect race, the lords of sea and land,

Is to unloose its bibs and belts and tell it to expand.

The race down Fate's great turnpike road has lurched from side to side,

With one good arm strait-jacketed and one good ankle tied ;

And thus, through many sun-parched days and many storm-drenched nights,

With all its chain- gang fetters on, has climbed to starry heights;

And gazing down the vista of the journey that remains

It asks no staff, no crutch, no help, but says, "Take off the chains ! "

One man and woman make one man. Is either half denied

The fullest freedom of its rights? The whole man then is tied.

The race is fettered foot and wrist, a hampered chain-gang, when

'Tis bound by fractional half-laws enacted by half-men.

One man and woman make one man, with self-same rights to be ―

Take off the half- man's shackles, then, and set the whole-man free.

To drain the moral Dismal Swamp and cleanse the social fen

We need the power of whole-laws enacted by whole-men.

The half-man since the years began has staggered towards the light

And climbed to many a table-land and many a star-kissed height;

But down the vistaed distance far are summits more sublime

And mantled peaks, beloved of heaven, which the

whole-man shall climb.

The cosmic yeast is working; the centuries ripen fast ;

And strange new shapes are looming dim from out the distant Vast;

Strange sunbursts on strange mountains, wide gleams on many a sea.

Let the whole-man march unfettered toward the greatness yet to be;

Let him front the coming glories and the grandeurs that remain

With feet ungyved and fetterless and hands without a chain.

Commentary

Foss, in much of his early work, is unreflectively sexist in a way we don’t much tolerate anymore. He’s not a misogynist, but he’s very gendered in how he thinks of people’s roles. (Similarly, he’s the specific kind of benevolent racist who writes that deep down, everybody is white in the soul.) He sometimes uses “men” in a gender-neutral sense2, but inconsistently3, which is the worst of both worlds, because when he imagines America saying “Bring me men to match my mountains” we don’t know what kind of “men” he means. (That line used to be prominently displayed at the U.S. Air Force Academy, but was taken down in 2003 in lieu of responding to a sexual assault scandal.)

He evolved. Seeing women start to take over his libraries, as both patrons and librarians, must have been part of it. The Half-Man and the Whole-Man is his most straightforwardly feminist poem, but others in the same collection show him experimenting with changing his language from “him” to “him or her” (sometimes “her or him”) and “men” to “men and women.”

The other noticeable change is in the nature of his optimism. His earlier poems called for optimism, saying that we should never give up hope. After the Wrights flew at Kitty Hawk, after victory in the Spanish-American war, his poems began instead to express optimism, a positively giddy confidence that this coming century would be an American century and a time of wonders.

The Coming Century

If the century gone, as the wise ones attest,

Exceeds all the centuries before it,

Then the century coming will better its best

And tower immeasurably o’er it.

And, if miracles now are coming to pass

Right here in your and my time,

Why, miracles then will be thicker than grass

And as common as flies are in fly time.

We will send down our pipes to the Earth’s burning core

Where the smithy of Vulcan is quaking,

And the fires that make the volcanoes outpour

We will use for our johnny-cake baking.

And then we will bridle and harness the tide

And make the pulse beat of the ocean

Provide the propulsion when Baby shall ride

And keep his small carriage in motion.

We will hitch the East wind to the crank of our churn

And make us a butter to “brag on”;

By projecting a psychical impulse we’ll turn

The wheels of a furniture wagon.

We’ll make yellow squashes from nice yellow dirt

Scooped up from our pastures and beaches;

On Sahara some chemical compound we’ll squirt,

And the sand will evolve into peaches.

And a hundred strong men by concentring their will

Ride straight to one point, like a plummet,

Will turn upside down a respectable hill

And spin it around on its summit.

Our buildings we’ll build of solidified air

‘Way up from the sill to the skylight,

With trimmings of brownstone surpassingly fair

Of solidified air of the twilight.

We will fly through the air from New York to the Rhine,

Through Germany, Lower and Upper,

Stop off, if we like, in Geneva to dine

And come back to New York for our supper.

If we don’t wish to fly we will throw our own thought,

Yes, each throw his thought to his sweetheart,

By a kind of a mental telepathy shot,

A method by which heart can meet heart.

We shall learn of the beings who people the stars

And add to the cosmical mirth, then,

By telling new jokes to the people of Mars

And hear them laugh back on the earth, then.

Ah, many trans-cosmic debates shall be whirled,

And long be the parleys between us;

One end of the dialogues fixed in this world,

And the other located in Venus.

Commentary

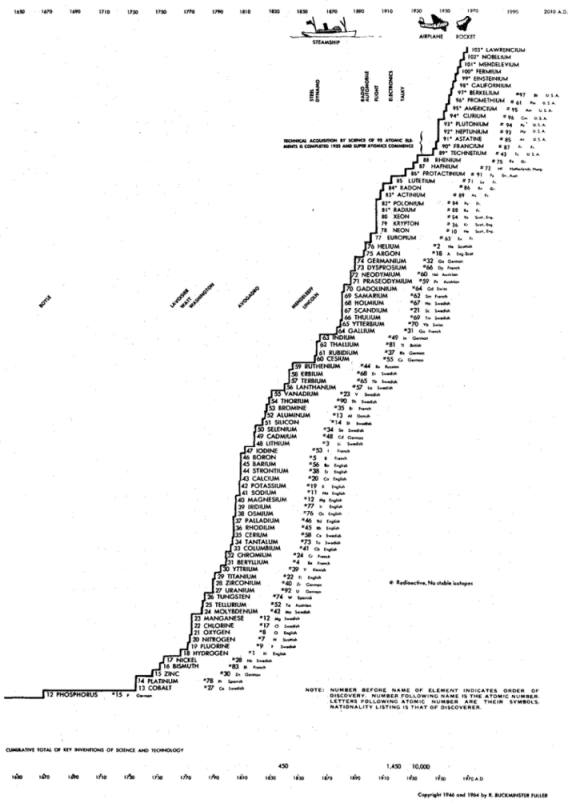

It’s hard to believe, but people mostly hadn’t quite worked out yet that the rate of change was accelerating. We were still decades away from Buckminster Fuller publishing a precursor to Ray Kurzweil’s famous exponential curve graph.

Foss captures a key aspect of our zeitgeist: humanity as a whole might be accomplishing miracles, but the average person’s experience of them will be more personal and mundane—using geothermal energy to bake johnny-cakes and satellites to text our sweethearts.

The Infidel

Who is the infidel? 'Tis he

Who deems man's thought should not be free,

Who'd veil truth's faintest ray of light

From breaking on the human sight;

'Tis he who purposes to bind

The slightest fetter on the mind,

Who fears lest wreck and wrong be wrought

To leave man loose with his own thought ;

Who, in the clash of brain with brain,

Is fearful lest the truth be slain,

That wrong may win and right may flee—

This is the infidel. 'Tis he.

Who is the infidel? 'Tis he

Who puts a bound on what may be;

Who fears time's upward slope shall end

On some far summit — and descend ;

Who trembles lest the long- borne light,

Far- seen, shall lose itself in night;

Who doubts that life shall rise from death

When the old order perisheth;

That all God's spaces may be cross't

And not a single soul be lost -

Who doubts all this, who'er he be,

This is the infidel. 'Tis he.

Who is the infidel? 'Tis he

Who from his soul's own light would flee;

Who drowns with creeds of noise and din

The still small voice that speaks within ;

'Tis he whose jangled soul has leaned

To that bad lesson of the fiend,

That worlds roll on in lawless dance,

Nowhither through the gulfs of chance;

And that some feet may never press

A pathway through the wilderness

From midnight to the morn- to - be-

This is the infidel. 'Tis he.

Who is the infidel? 'Tis he

Who sees no beauty in a tree;

For whom no world-deep music hides

In the wide anthem of the tides;

For whom no glad bird-carol thrills

From off the million-throated hills;

Who sees no order in the high

Procession of the star-sown sky;

Who never feels his heart beguiled

By the glad prattle of a child;

Who has no dreams of things to be -

This is the infidel. 'Tis he.

Commentary

Foss had faith in God’s plan. Though often cynical about religion, he was a practicing Methodist, and part of his optimism came from his beliefs. Here, he uses this aspect of his philosophy to make a point about liberalism—why are you so worried about heresy, if you truly believe in an almighty God? How can you believe in the Rapture and not the Whig theory of history? Anyone trying to suppress progress or free thought, even if they do so in the name of religion, must be a doubter.

We preach a secular version of this in the U.S., but not enough. Suppressing illiberalism is not liberalism. Banning woke shibboleths is not anti-woke. Telling people to stop thinking and trust the experts is not being pro-science. Whenever you find yourself policing what people say, rather than critiquing their speech—you’re the infidel. 'Tis you.

The Higher Fellowship

Are you one of my gang?

Yes, you're one of my gang.

The same job is yours and mine

To fix up the earth,

And so forth and so forth,

And make its dull emptiness shine.

The world is unfinished; let's mould it a bit

With pickaxe and shovel and spade;

We are gentlemen delvers, the gentry of brawn,

And to make the world over our trade.

And I love the sweet sound of our pickaxes' clang,

I'm glad to be with you. You're one of my gang.

Are you one of my crew?

Yes, you're one of my crew,

And we steer by the same pilot star,

On a trip that is long

And through storms that are strong;

But we sail for a port that is far.

O, the oceans are wide, - and we're glad they are wide

And we know not the thitherward shore, ――

But we never have sailed from the Less to the Less

But forever from More to the More.

And we deem that our dreams of far islands are true.

Let us spread every sail. You are one of my crew.

You belong to my club?

Yes, you're one of my club,

And this is our programme and plan:

To each do his part

To look into the heart

And get at the good that's in man.

Detectives of virtue and spies of the good

And sleuth-hounds of righteousness we.

Look out there, my brother! we're hot on your trail .

We'll find out how good you can be.

We would drive from our hearts the snake, tiger, and cub;

We're the Lodge of the Lovers.

You're one of my club.

Do you go to my school?

Yes, you go to my school,

And we've learned the big lesson, Be strong!

And to front the loud noise

With a spirit of poise

And drown down the noise with a song.

We have spelled the first line in the Primer of Fate;

We have spelled it , and dare not to shirk -

For its first and its greatest commandment to men

Is, "Work, and rejoice in your work."

Who is learned in this Primer will not be a fool

You are one of my classmates. You go to my school.

You belong to my church?

Yes, you go to my church,

Our names on the same old church roll-

The tide-waves of God

We believe are abroad

And flow into the creeks of each soul.

And the vessel we sail in is strong as the sea

That buffets and blows it about;

For the sea is God's sea as the ship is God's ship

So we know not the meaning of doubt,

And we know, howsoever the vessel may lurch

We've a Pilot to trust in. You go to my church.

Commentary

Foss’s poems are for you. You don’t need to believe in his God, live in his town or country, or feel universal compassion as easily as he does. You’re part of his club. You go to his church.

Two Gods

I

A boy was born 'mid little things,

Between a little world and sky,

And dreamed not of the cosmic rings

Round which the circling planets fly.

He lived in little works and thoughts,

Where little ventures grow and plod,

And paced and ploughed his little plots,

And prayed unto his little God.

But as the mighty system grew,

His faith grew faint with many scars;

The Cosmos widened in his view

But God was lost among His stars.

II

Another boy in lowly days,

As he, to little things was born,

But gathered lore in woodland ways,

And from the glory of the morn.

As wider skies broke on his view,

God greatened in his growing mind;

Each year he dreamed his God anew,

And left his older God behind.

He saw the boundless scheme dilate,

In star and blossom, sky and clod;

And as the universe grew great,

He dreamed for it a greater God.

Commentary

Foss was a fan of Herbert Spencer, a writer and philosopher who popularized and expanded on Darwin and Lamarck’s theories of evolution. Spencer coined the phrase “survival of the fittest,” as well as a definition of evolution that Foss cites in a different poem: the passage from incoherent homogeneity to coherent heterogeneity.

Foss, like Spencer, hopes here that religion will co-evolve with science, with each new revelation expanding our notion of the numinous.

The Wide-Swung Gates

The Genius of the West

Upon her high-seen throne,

Who greets the incoming guest

And loves him as her own;

The Genius of these States

She hears these modern pleas

For the closing of the gates

Of the highways of her seas.

"Fence not my realm, " she says, "build me no continent pen,

Still let my gates swing wide for all the sons of men. "

The Genius of these States,

She of the open hand,

Stands by the open gates

That look to every land:

"Come hence " (she hears the groans,

The distance- muffled din

Of millions crushed by thrones),

"Come hence and enter in. Shut not my gates," she says, “that front the in-flowing tide,

For all the sons of men still let my gates swing wide."

"What! leave thy bolts withdrawn? ”

Cry they of little faith,

"For Europe's voided spawn,

Spores of the Old World's death?

These monsters wallowing wide

In anarchy's black fen?"

"Peace, peace, it is my pride

To make these monsters men;

With the Great Builder work that knows not Greek or Jew,

And from an old-world stuff fashion a world anew.

"And in my new- built state

The tribes of men shall fuse,

And men no longer prate

Of Gentiles and of Jews:

Here seek no racial caste,

No social cleavage seek,

Here one, while time shall last,

Barbarian and Greek:

And here shall spring at length, in narrowing caste's despite,

That last growth of the world, the first Cosmopolite.

"A man not made of mud

My coming man shall be,

But of the mingled blood

Of every tribe is he.

The vigor of the Dane,

The deftness of the Celt,

The Latin suppleness of brain

In him shall fuse and melt ;

The muscularity of soul of the strong West be blent

With the wise dreaminess that broods above the Orient.

"Here clashing creeds upraise

Their warring standards long,

Till the ferment of our days

Shall make our new wine strong.

Let thought meet thought in fight,

Let systems clash and clinch,

The false must sink in night,

The truth yields not an inch.

No thought left loose, ungyved, can long a menace be

Within a tolerant land where every thought is free."

The Genius of the West

Upon her high-seen throne

Thus greets the incoming guest

And clasps him as her own.

The Genius of these States

Puts by these modern pleas

For the closing of the gates

Of the highways of her seas.

"Fence not my realm," she says, "build me no continent pen,

Still let my gates swing wide for all the sons of men."

Commentary

Unsurprisingly, Foss has a fair number of anti-anti-immigration poems, all of which are quite politically incorrect today. I kind of have the impulse, though, to start nailing them to the doors of government buildings or something.

The Word

The Word Divine vouchsafed by God to man

Is uttered through the years of many an age;

And there are lips touched with the prophet's rage

To-day, as there have been since time began:

Not to a far-off patriarchal clan,

To Idumean or Judean sage,

Did God alone indite a sacred page

In narrow lands, 'twixt Beersheba and Dan.

God's voice is wandering now on every wind

And speaks its message to the tuned ear;

And here are holy groves and sacred streams;

On every hill are sacred altars shrined;

And prophets tell their message now and here;

Young men see visions and old men dream dreams.

Commentary

Sam Walter Foss was a prophet.

If you ignore the whole linearity-of-time thing.

For example: And henceforward from that hour there were two live men in town -

The young Erastus Peterson and Dr. Sarah Brown.

For example: Yes, the farms is all deserted; there is no one here to see

But jest a few ol' women an' a few ol' men like me ;