In 1820, as today, being a knight didn’t come with much in the way of perks or responsibilities. It was a vague signifier of quality—you’d done some service for crown and/or country. So when Charles Aldis, a doctor, added that “Sir” to his name, it’d be reasonable to infer that he’d accomplished something significant, probably in the field of medicine.

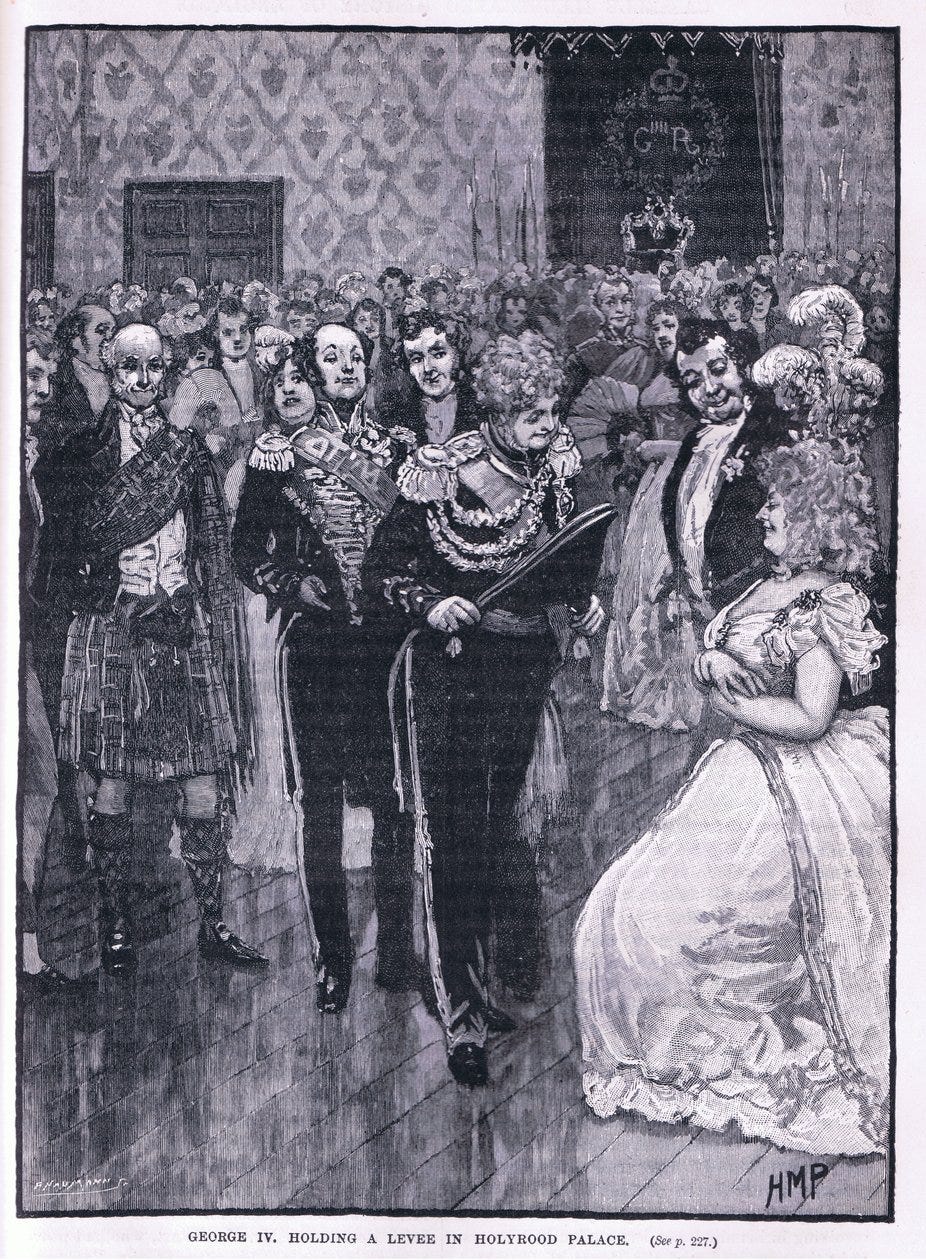

Actually, he was knighted via a social engineering hack. Aldis showed up at a levee of the new King George IV, lied his way inside, and then simply got in line to be knighted. George, who had only been king for a few months, certainly couldn’t be expected to know everyone due for a knighthood. He gave him the ritual two taps on the shoulders “with fist or blade,” and Charles Aldis had been irrevocably dubbed. There are circumstances where a knighthood can be revoked, but “oops” isn’t one of them.

So the Sir isn’t evidence of anything good from Aldis. Far from it. But, as it happens, he was one of the founders of modern medicine, responsible for innovations that have improved countless lives. This is his only known shenanigan, and it’s unclear why he pulled it. I do have a theory.

False Smoke, True Fire

In epistemology, the philosophical study of the nature of knowledge, cases like Aldis’s knighthood are known as “Gettier problems,” thanks to a 1963 paper by Edmund Lee Gettier III. Gettier, however, wasn’t the originator of the concept, and wasn’t particularly interested in it—he was just in a publish or perish situation and did the needful. Once he got tenure, epistemology never heard from him again.

The oldest known Gettier problems come from the 8th-century Tibetan epistemologist Dharmottara. He’d have used the Sanskrit word pramana for the field. Dharmottara tells two stories. In one, someone lights a fire and starts cooking food. Insects, smelling the food, gather in a dense cloud overhead. Someone far away sees only the cloud of insects, mistakes it for a cloud of smoke, and says “There’s a fire over there.”

In the other, a desert traveler heads towards what he thinks is water, but is actually a mirage. Luckily, though, there coincidentally is actual water right there, hidden under a rock.

These scenarios are highly problematic to a certain kind of person. Does the speaker in Dharmottara’s story know that there’s a fire? Beliefs can be mistaken or arbitrary, but the belief in the fire was neither—the fire was real, and the speaker was justified in saying that where there’s smoke, there’s fire. But if we treat that as knowledge, it’s hard to find a principled distinction between the fire story and the water story. Surely there must be some rigorous definition of knowledge where hallucinations don’t count.

Scrofula

Sir Aldis’s main focuses in medicine were cancer and scrofula. Scrofula is when the lymph nodes in your neck swell up, sometimes enough to create something that looks like a tumor. This can happen for a few different reasons, so modern medicine considers it more like a symptom than a disease, but people in the Middle Ages didn’t. By the time Aldis had started looking into it, there were centuries of wisdom on how to treat scrofula. There were three accepted treatments:

Hang figwort, a plant that looks like it has scrofula, around your neck. According to the well-attested Doctrine of Signatures, plants that look like your disease will cure it.

Inject mercury into your neck. Mercury is an antibiotic, so it might kill whatever’s making your lymph nodes swell. Don’t worry, the symptoms of mercury poisoning just mean it’s working.

Be touched by a king. European kings rule by divine right and therefore have magical powers, and one of them is curing scrofula. Scrofula is also called “king’s evil” for this reason.

These three cures have three different epistemic statuses. Being touched by a king didn’t work. I am 99% sure. Injecting mercury sometimes worked, because sometimes bacteria in the neck were the root cause, but the cure was worse than the disease. Figwort was a Gettier case. The doctrine of signatures is nonsense, but figwort does contain compounds that reduce swelling and irritation, so it was a decent treatment. Not great, but much better than the other two.

But how do we know that?

Empiricism, wrote Aldis, was the only way we could move forward.

Let us therefore, “reasoning only from what we know,” confine ourselves to the limited sphere of our understanding, and not indulge in chimerical disquisitions, losing ourselves in the labyrinths of reverie. “Nil admirari” [“let nothing awe you”] should be the motto of every philosopher. To demonstrate, not to surmise, is the business of philosophy.

— Charles Aldis, 1811.

A Remnant of Exploded Witchcraft

“Do experiments and see what works” is a beyond-trite answer today, but in his time, “empiricism” and “quackery” were considered synonyms. Here’s Aldis’s frenemy1, Mary Wollstonecraft:

I was informed, by a man of veracity, that two persons came to the stake to drink a glass of the criminal's blood, as an infallible remedy for the apoplexy. And when I animadverted in the company, where it was mentioned, on such a horrible violation of nature, a Danish lady reproved me very severely, asking how I knew that it was not a cure for the disease? Adding, that every attempt was justifiable in search of health. I did not, you may imagine, enter into an argument with a person the slave of such a gross prejudice. And I allude to it not only as a trait of the ignorance of the people, but to censure the government, for not preventing scenes that throw an odium on the human race.

Empiricism is not peculiar to Denmark; and I know no way of rooting it out, though it be a remnant of exploded witchcraft, till the acquiring a general knowledge of the component parts of the human frame, become a part of public education.

Aside from her radical idea that everyone should be entitled to a free education for their children, Wollstonecraft was expressing the standard view of her time—any evidence-based medical claim was almost certainly a scam. Only doctors whose treatments were backed by a sound theory, gotten from a respected book, could be trusted.

Aldis, on the other hand, was raised with a Quaker mistrust of authority. He was a devotee of Francis Bacon, not the sort of person who would dismiss a cure for apoplexy out of hand. He tried out all sorts of different proposed treatments for cancer and scrofula, without worrying too much ahead of time about why they supposedly worked.

So I think he’d have been bound by principle to check all three traditional scrofula cures, despite one being a little inconvenient. While some kings held mass healing events where they’d go around and touch everybody’s infected necks, the Georges were, for some mysterious reason, not into this. How, then, to get someone with scrofula to be touched by a king, so that you can do before-and-after examinations? Shenanigans, that’s how! Recruit someone with mild scrofula, give him clothes to wear and names to drop so that he can impersonate you, and have him sneak onto a line to be tapped on the shoulders by the king.

The Fallout

Aldis was one of two, both doctors, whom the papers dubbed “surreptitious knights.” The other was Sir Francis Columbine Daniel, who was invited to a later levee due to being a well-connected Freemason. The masons later claimed that he’d gotten onto the wrong line by mistake.

The government, once they noticed, chose to share the names of the dubiously dubbed pair, but take no other action against them. They did improve the system around dubbing—you now needed to present official papers, not just say “I’m here for that knighthood you promised.” No further cases are reported.

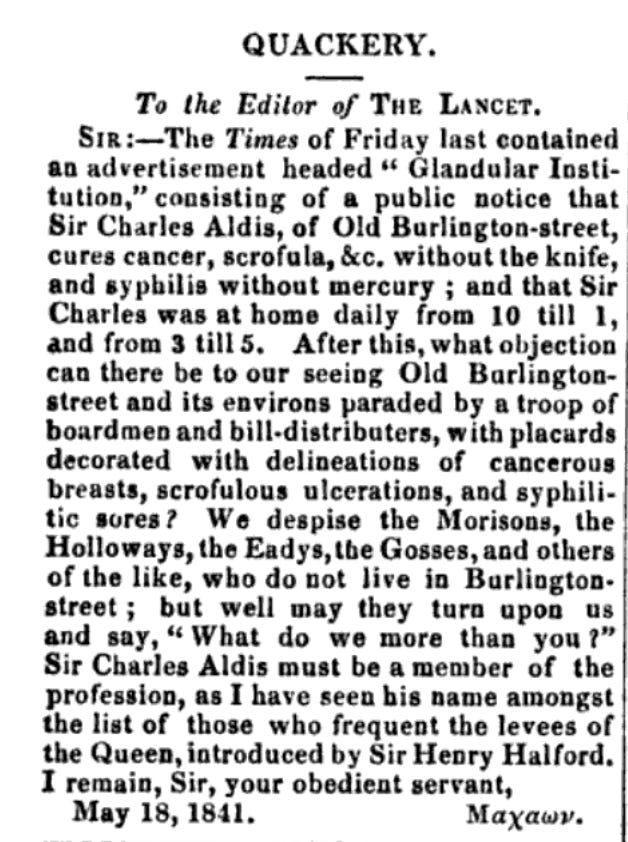

All the news coverage at the time, aside from finding the whole thing hilarious, took it as a given that the two were quacks: snake oil salesmen trying to steal a veneer of legitimacy so they could charge more people for phony medical treatments. It’s “an advertisement,” wrote the Morning Chronicle.

Aldis was expelled by the Royal College of Surgeons, and his methods were duly ridiculed. He’d written that injecting patients with mercury actually shortened their lives, on average, and so we should probably stop doing it so much. Tumor-like swellings should be treated topically, he wrote, and only surgically removed if that fails, as surgery is painful, dangerous, and often ineffective. This was represented in the press as “he claims to be able to cure cancer and scrofula without mercury or the knife.” They left out the fact that he didn’t charge for his treatments. His “Glandular Institution” was supported by voluntary donations. Without that little detail, he indeed sounds all sorts of sketchy.

The other knight is a trickier case. There’s some evidence that Francis Daniel might have scammed his way into the Freemasons, and some that he really was a bit of a quack. But all that might be sneers and defamation. Less of his medical writing has survived, making it hard to determine what his epistemological philosophy was. The Freemasons rate him highly, for what it’s worth.

Why so much hate on Daniel in particular? His section in the 1824 The London Medical, Surgical, and Pharmaceutical Repository Annals of Quackery subtly suggests one possible reason.

The public had been a long time imposed on by Sir Columbine Daniels, the Israelite (since defunct, thank heaven! for the sake of his patients,) under the specious cover of a Medical Board and from which doubtless the [Jewish quacks described previously] took the hint…These vampires contrived to bleed and physic their ill-starred patients to some purpose, and between them they declared, (upon the “New Testament”) that they had cured THIRTY THOUSAND PERSONS!! “Credat Judæus.”

I don’t see any other reference to him being Jewish, but it’s plausible. The connection between Jews and Freemasons is a false conspiracy theory now, but it was true then. Daniel was inducted into the Freemasons one year before Baron Nathan Mayer Rothschild.

But it wasn’t just anti-Semitism. The entry concludes by denouncing Aldis as well:

Sir Columbine, Sir Charles, and Sir, the Lord knows who! puff themselves off under their newly acquired titles, which seldom fails to recommend them to the stupid credulity of the many, while it appears in its true colours of hypocrisy and empyricism to the few, a mass of ridicule and contempt.

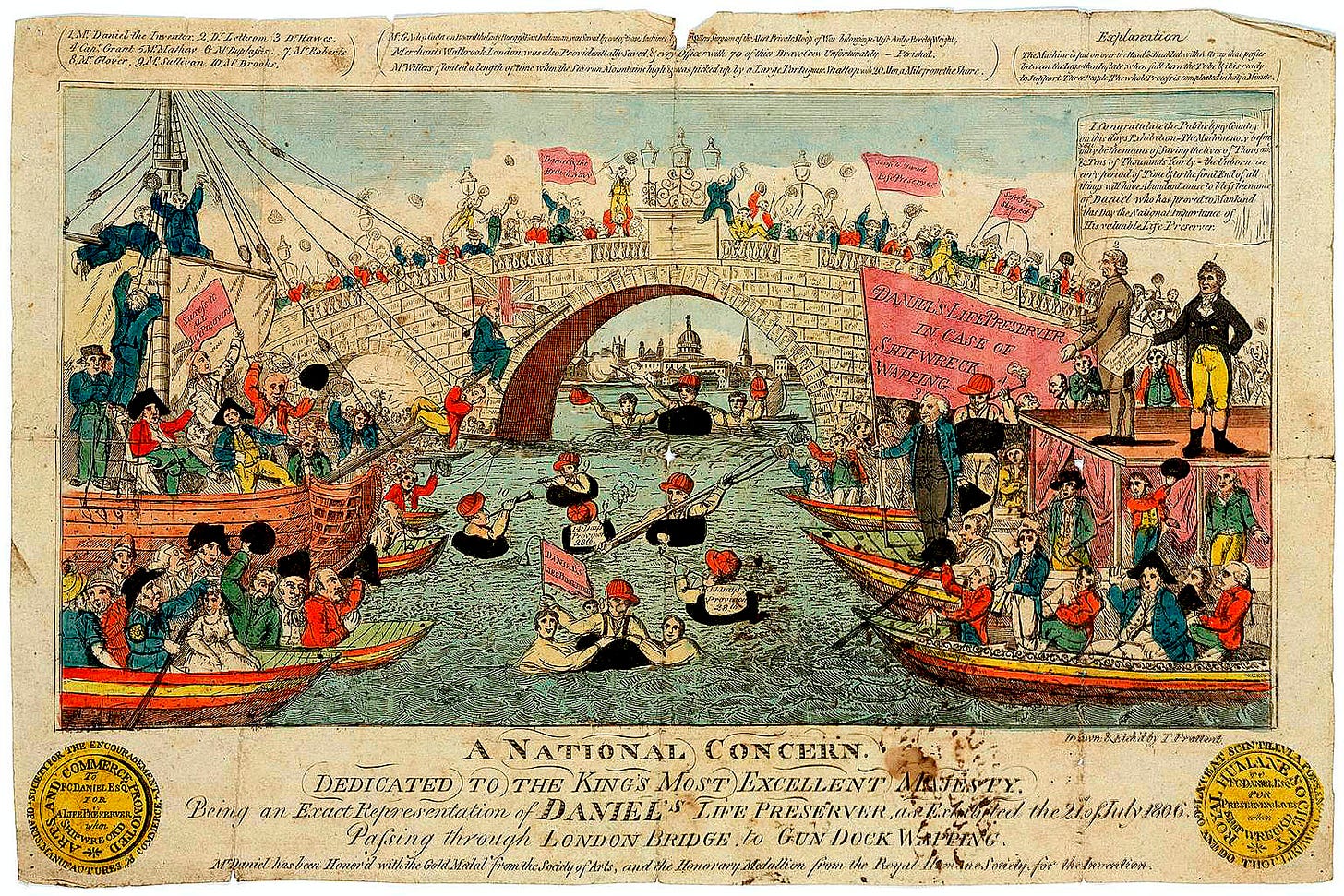

Daniel’s focus was on helping sailers, and his work extended beyond experimental treatments. His design for a sea medicine chest was widely adopted. His public image as a shameless empiricist comes mainly from how he promoted another nautical invention of his: a life preserver. Emergency floatation devices were an old idea, but they were widely considered too cumbersome for practical use. Daniel came up with a simple and cheap design for an inflatable ring. To prove its efficacy to the public, he and some associates spent a day floating down the Thames, hands-free, demonstrating that they had the freedom of motion to do things like smoke a pipe and load a gun. It was quite a scene.

If you trust his advertisements, anyway. The conservative magazine John Bull remembered the day differently, writing after the knighting scandal:

Sir Harlequin Daniels, the other worthy, is known as the inventor of a “Life Preserver” which we remember some years ago to have seen him exhibit on the river Thames; at least we remember to have seen a middle-aged man naked, with a cocked hat upon his head, smoking and playing the fiddle, as he swam, bobbing and toppling, through one of the arches of Westminster bridge, to the infinite delight of sundry small boys; but whether it was the pre-Chevalier himself or an Esquire we are not quite certain.

Daniel’s life preserver demo was, to the Tories, a powerful demonstration of the dangers of “empyricism.” The ignorant public was duped en masse into thinking that something blatantly ridiculous could save them from drowning, merely because they’d all seen it happen in broad daylight in the middle of London.

(The article was titled “Quack Quack Quack.”)

Many Such Cases

In the long run, people seem to have literally forgotten that the knighthoods were unauthorized. Obituaries and biographies of Aldis often just say “he was knighted, but there’s no record of for what.” And Aldis was largely vindicated by history—in particular, his controversial advocacy for vaccination, with the benefit of hindsight, must have done a ridiculous amount of good. He argued for clean drinking water as a public utility, which also seems obviously good in retrospect. The Quakers, as pacifists, expelled him for treating Navy men, but in utilitarian terms he’s got a great score.

He didn’t have any good statistical methods at his disposal. But just trying to see what actually worked was a superpower. He certainly didn’t get everything right. I don’t think we tend to use topical arsenic much these days. But he didn’t pretend to have a perfect model of the world.

Nowadays we follow his lead. There’s a lot of modern medicine these days where we know it works, but not how. It’s better than the reverse: knowing how something is supposed to work, but not whether it does.

We took too long to get here because people thought it was gross. Wollstonecraft just wanted to do whatever it took to get Danes to stop drinking fresh human blood. The NIMBY in The Lancet didn’t want a proliferation of graphic ads for dodgy cancer treatments. Not bad goals, but it’s bad that they tried to achieve them by basically halting all medical progress.

The purity mindset is an enemy of empiricism. Gettier problems only feel like paradoxes if you think there must be such a thing as a perfect, universal definition of a word, a “knowing/not-knowing” binary. That leads to the sort of rigid epistemology that declares absurdities like “absence of evidence isn’t evidence of absence,” “past performance is not indicative of future results,” or “you must make no claims in the absence of proof.” When you think probabilistically, the paradox dissolves.

But empiricism has another enemy: a poor epistemic environment. Londoners really were being spammed constantly with phony and dangerous cures. Anybody could say “this treatment has cured 30,000 people, including my own sister.” If they got a bad reputation, they could just start using a different name. This is the sort of situation I talk about in Lace and Libels: a theoretical backing, with citations from Galen, requires more work to create. Proof-of-work makes it harder to scam, so the guy writing in Latin might legitimately be a better bet. As would a knight. Not foolproof, but a good heuristic in a market for lemons.

The current refrain of “trust the science!” and “trust the experts!” is best understood as a symptom, not a disease. It’s a reaction to a decline in epistemic health. Science only works if you don’t believe in it. Skepticism is its engine. But when the alternative to expert consensus looks more like “global warming is fake” than “hm, it looks like there’s strong preliminary evidence that FDA guidance is wrong here…” You can understand why some people might be a bit skittish about outlandish claims.

Just like in the 1800s, I think the only way out is through. Insisting that the experts are always right is the opposite of evidence-based thinking. We should be trying to promote truth-seeking, not suppress falsehood. Stir more honesty into the pot to dilute the lies.

Empiricism is messy, embarrassing, and often totally wrong. But even when you’re chasing a mirage, at least you’re moving.

The anonymous 1803 book A defence of the character and conduct of the late Mary Wollstonecraft Godwin is widely attributed to Aldis, but there are some skeptics. He was definitely in her circle, though.