The Student Activist Who Brought the Revolution to Europe

A July 4th celebration of Jonathan Loring Austin, one of the many forgotten heroes of American independence.

I congratulate my country on the return of this anniversary—Hail auspicious-day! an era, in the American annals, to be ever remembered with joy, while as a sovereign and independent nation, these United States can maintain with honour and applause the character they have so gloriously acquired!

— Jonathan Loring Austin, speaking in Boston, July 4th, 1786.

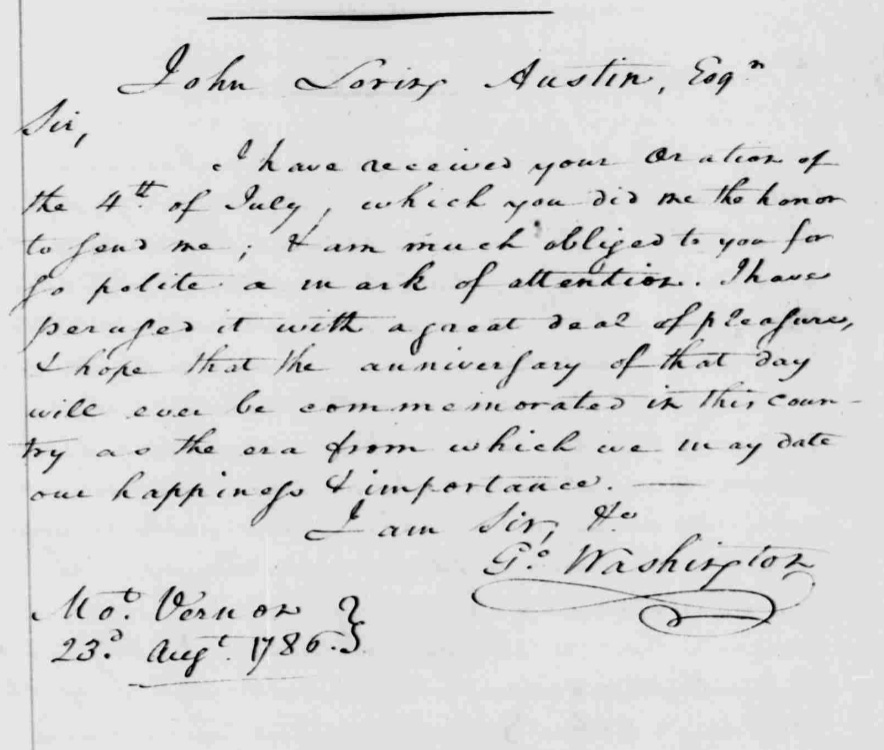

Jonathan Loring Austin’s speech in Boston, on the 10th anniversary of Independence Day, warranted this brief note of thanks from soon-to-be-President George Washington. But twenty years earlier, almost to the day, he gave a speech nearby that was not so well-received by the powers in charge.

Harvard, in 1766, was a conservative island in a turbulent colonial sea. In its 130-year history, no student protests had ever been recorded. Commencement addresses were given exclusively in Latin. You could raise all the hell you wanted after you graduated1, but if you wanted your diploma, you had to comport yourself like a gentleman. That all changed in July. One of the graduating students chosen to speak at commencement was too overjoyed at the repeal of the Stamp Act to wait until it was safe. Jonathan Austin, age 18, astonished those present by giving his speech in English. Not only that, but rather than talking about the classics, he spoke about contemporary politics. As a student! I don’t think we have a record of what, exactly, he said, but we do have this description: “The boldness of some of the sentiments were not much approved by the college government and had well nigh cost the candidate the honors of his class.” But even Harvard must have balked at expelling a student on the stage of his own commencement. So, soon after preaching revolution in his forbidden native tongue, his schoolmates watched as the powers that were, with great reluctance, gave him his diploma.

After that, Harvard was different. Forever. Two months later, students were protesting over being served rancid butter. It’s the first known student protest anywhere in the country. The ringleader, Asa Dunbar, was not expelled, and became his own kind of founding father of Harvard anarchists. His daughter, Cynthia, was an abolitionist who harbored fugitive slaves in the Underground Railroad. Her son was Henry David Thoreau.

At this period of our conflict, America appears blessed with the peculiar attention of heaven. These States united to the astonishment of our enemies, adopted measures, the effects of rational and dispassionate deliberation, pursued them with attention, and with caution and firmness carried them into execution: measures, which will ever be esteemed by all nations as the most prudent and decisive, evincing how sacredly dear we considered our liberties, and how jealous of our honor in the defence of them: measures which exhibit a striking proof, that decency and order should ever be the established principle of a free people, and that liberty, though held tenacious, should never be sullied with rashness.

Austin joined the Revolutionary Army as soon as it existed. He served as a major in a volunteer regiment defending Portsmouth, New Hampshire, and later as Secretary of War in Massachusetts. Then, in October of 1777, he was sent on a unique and vital mission.

The legendary first marathon was run to bring news of the outcome of a battle, some say in order to ensure that the truth of victory could outrace lies about defeat. In the early days of the Revolutionary War, the empire’s ability to lie with impunity rose to an unprecedented level. Separated from the front by an ocean that usually took months to travel, the British government could simply seize and destroy every single letter bringing news of revolutionary victories, then publish whatever narrative it wanted without fear of contradiction. In Britain and mainland Europe, everyone had no choice but to believe them that the revolt was in complete disarray, with the various colonies turning on each other as the Redcoats inexorably captured city after city.

Benjamin Franklin was in France, sent there to request aid. But he wasn’t making that request. He knew that if he asked the French now, they’d refuse to back what was so clearly the losing side.

IF we frequently revert to first principles, and often bring to our remembrance the events which took place at the commencement of this contest, it will enable us to form a just estimate of that INDEPENDENCE, which has cost so much blood and treasure. It will lead us, with one voice, to acknowledge the kind and protecting hand of heaven stretched forth for our relief, when destitute of all human aid. Unexperienced in the art of war; unprovided with arms and ammunition, and without the support of a single ally, we dared to oppose the force of Britain, a force even dangerous to the safety of Europe.

The opposition party in Parliament, the Whigs, were in a similar fix. They were worried that King George planned to erode freedoms back home, and saw the revolutionaries as natural allies. Parliament was the only entity with the power to end the war. But with the situation as it seemed to be, there was no way to safely align themselves with the rebels.

Massachusetts sent Austin to break through the firewall, on the fastest ship they could charter. The pastor at the Old Brick Church led his congregation in prayer for Austin’s safety and success. Less than a month later, Austin arrived in Nantes, France, with a ship full of documents about the surrender of General Burgoyne and his army. Benjamin Franklin, who had been hoping for good news but never expecting it to be this good, afterwards could never see Austin without grinning at the memory. Armed with Austin’s cargo, Franklin began his campaign in France in earnest.

From there, Austin traveled to England. Franklin warned him not to take any documents from America for this mission. Apparently worried that he’d disobey this instruction, risking his own neck to improve his odds of success, Franklin made him burn all the papers he still had on him while Franklin watched. Instead, he gave him letters of introduction to the leaders of the English opposition.

Austin spent the next few months making the London circuit. By day he’d watch the debates in Parliament. In the evening, he ate dinner with the more sympathetic-seeming of the bunch, and answered their endless questions about the true state of the war and of America. In the end, they believed him. Parliament spectators were soon treated to the sight each day of an entire party wearing homemade replicas of the uniforms of George Washington’s army.

BY reverting to that cimmerian darkness from which we have just emerged, I mean not to open fresh wounds, or to raise an unmanly inveteracy against our enemies; but rather, to rivet on our minds the injuries we have suffered, and to impress those cruelties so wantonly exercised in the course of the late war; that our feelings may be more poignant at the recollection; and that we may be roused not to revenge, but to a steady uniform perseverance in support of the freedom and independence so happily acquired.

Austin was then sent on yet another mission, to try to get a loan from the Dutch. On this journey, he was finally captured by the British, who tortured him for information, apparently in vain. Franklin called in a favor and got him freed before his captors could make good on their threat to tie him to the mast of a battleship. Austin made it to Amsterdam, but the Dutch refused to take him at his word on the state of the union. They could only give him a personal line of credit, they said, as there was no evidence his government would exist long enough to repay them. Austin sighed and bought what war supplies he could out of pocket, which amounted to a few uniforms. John Adams, who was on a similar mission, wrote him a commiserating letter, saying he had “the consolation however that you have had as good luck as any one else” at getting the Dutch to invest in their startup.

Well, two out of three was good enough. Franklin won his alliance with France, and soon the Parliamentarians in blue were able to form a coalition government for just long enough to end the war, granting the rebels independence. Austin returned home a hero. He ended up as the Secretary and Treasurer of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. Ironically, he was memorialized as one of the first New Englanders to be a true gentleman, thanks to his European sophistication. His son went to Harvard.

BUT I forbear—PEACE with her balmy wings affords a pleasing reverse.—The sound of the trumpet, and the alarm of war are no longer heard in our land. We may now, with the highest satisfaction, anticipate the future glories of these United States, and with pleasure behold our demolished towns, like the phoenix from her ashes, rising to our view, with improved beauties.—While the historian records the destruction of Charlestown, and the ever-memorable battle on BUNKER'S HEIGHTS, he will not be unmindful to relate, that from the ruins of the old, a new town is now rising, on a more enlarged and regular plan.

Nor will he forget to notice, with equal admiration, the enterprize and ingenuity of our inhabitants, in the rapid construction of that extensive and noble BRIDGE across Charles river, which joins her to this metropolis. May the late sufferings of our friends and neighbours, be more than compensated by their future advantages; may the origin of their distress prove the instrument of their growth and prosperity.

Today, July 4th, 2024, I’m not interested in engaging in that sacred and vital American pastime of criticizing our country. Tomorrow, maybe. Today is for celebration and building bridges. Let’s pour out some tea for that 18-year-old rebel, he who first defied Harvard, who smuggled truth into France, who opened up a second front in the capital of the adversary, who survived torture and a bad credit score. Sometimes, the most powerful thing you can do is to speak the truth.

Immediately after, usually. Graduation ceremonies were notoriously wild as the new alums finally let loose. During the 1745 siege of a French fort in Cape Breton, the New England besiegers realized that the French inside were scared to attack them, because they worried that soldiers let out of the fort would immediately desert or defect. So the New England troops started treating the siege as a kind of extended, heavily armed party. One soldier wrote afterwards that it was “carried on in a tumultuous random manner, and resembled a Cambridge commencement.”

"Sometimes, the most powerful thing you can do is to speak the truth." Amen.