Dutch people really like the color orange, because of the Princes of Orange, and they have historically grown a lot of carrots. There are varying accounts of how exactly these two facts are related, ranging from claims that they invented the orange cultivar of carrots to somewhat implausible claims that it’s a complete coincidence. The most likely answer is that their climate suited carrots, and they preferred to grow orange carrots, because Orange, and this eventually lead to that color, specifically cultivars derived from Dutch yellow carrots, becoming the dominant carrot color worldwide. (Ed: There remain some Orange Carrot Skeptics on this point, so I’ve written up the case here.)

This is interesting, though, because it implies an unusually clear impact for language. If the Dutch royal line had been the House of Purple instead, we might well have settled on purple carrots, which are lower in carotene. So why is it called the House of Orange, anyway?

Orange Julius

It’s the rare road that doesn’t lead to Rome if you follow it long enough. The House of Orange was named for a city in the south of France, originally founded by the Roman Empire for veterans of the second legion, who had helped conquer it. They attempted to name the place “Colonia Julia Firma Secundanorum,” Latin for “the colony founded by the House of Julia for the second legion,” but nobody had time for that. (The House of Julia was more successful in giving its name to its most famous member, Gaius, who everybody now calls Julius Caesar.)

Instead of that long official name, the retired legionaries called the city Arausio. This is probably a reference to a Celtic river god, although we don’t have much evidence for Arausio worship outside this context. It makes sense, though—Arausio was built right on a river.

Eventually, the local dialect of Latin evolved into a precursor of modern French, in which “Arausio” is a weird name. So some time in the Middle Ages it was merged with the nearest-sounding French word, “orange.”

The Prince of Orange as German Propaganda

Also in the Middle Ages, Germany conquered France. Well, no, that’s a very anachronistic way of putting it. Neither country existed. An empire whose capital was in modern-day Germany annexed several regions of modern-day France, and different people preferred different narratives around that.

Frederic Barbarossa, the emperor in the second half of the twelfth century, had a very specific narrative in mind. “The Holy Roman Empire has taken all Christian lands under its protection, to be ruled by local princes in the name of the Emperor and God.” This narrative was a little awkward to promote, because of the Pope. Unlike Barbarossa, he was actually headquartered in Rome, and was more definitively Holy. The church had a great deal of tangible power, in those days. Barbarossa was effectively in a long-running cold war with his own head of faith—at the peak of the conflict, he helped install a different one in Rome and declared Pope Alexander III to be an antipope.

The creation of the Princes of Orange is generally seen as a move in this cold war. By elevating a local lord to Prince status, Barbarossa added an air of legitimacy to his rule over the area. This meant that at least the soft power of the Church had a counterbalance—a cardinal probably outranks an earl, but maybe not a prince.

Moving House

Okay, but the city of Orange is in France, and the House of Orange isn’t. What’s the deal there?

The Holy Roman Empire had a disastrous century, culminating in Voltaire’s 1756 observation that not only was the Holy Roman Empire neither holy nor Roman, it also wasn’t really an empire anymore. Large chunks had been ripped off of it by various external powers and independence wars. The Princes of Orange tried to be independent rulers, not just of their capital city, but of whatever disconnected regions of the disintegrating empire they were able to grab. By the time Orange was eventually conquered by King Louis, they’d established themselves in the newly-independent Dutch Republic, abandoning their former capital.

Here, they had two rival powers. Like Barbarossa, they had to contend with the Church. In addition, the seven United Provinces that formed the Republic had formed a federated government in the process, one with elections, provincial Stewards, and a parliament, not a line of kings. It was often unclear who had the most power. They would sometimes Frankenstein together an artificial king by electing the current Prince as Steward of most or all of the provinces simultaneously. Or sometimes they’d write it into federal law that the Princes were forbidden from holding elected office.

The House of Orange eventually won, more or less. They ended the republic and ruled as Kings and Queens. A part of their victory, albeit not the final one, came when a conceited demagogue named Tromp incited a mob to storm a building in the capital, telling them that the republicans there were trying to steal the country from the Prince of Orange. I learned about this bit while first researching this story, sometime during the Obama administration, so you can imagine how surreal it was to watch the tragedy repeat as farce. (They’re almost certainly not related. The expat descendants of Tromp all changed their names to “van Tromp”, because they incorrectly believed “van” made a name fancier like its German cognate “von” does.)

Orange Carrots As British Propaganda

In broad strokes, we can credit mass media for the way we settled on just one color for carrots. Bugs Bunny, in 1940, imitated a scene in a black and white movie where Clark Gable ate a carrot. It became his signature move. Carrots were already predominantly orange by then, but seeing Bugs exclusively eat orange ones persuaded our impressionable youth that that’s all there was, folks. At least, that’s what impressionable youth were watching in the U.S. In Europe, in 1940, people were kind of busy.

In the 1940 Battle of Britain, Nazi bomber planes would fly over UK cities at night, bombing indiscriminately to try to force a surrender. Instead, British fighter pilots would scramble (a military term) to shoot them down first. They were able to find them in the dark due to a secret expansion of the military’s radar capabilities. Germany knew about radar, but they didn’t know that it was integrated with the air force. If they’d figured it out, they might’ve focused on bombing the radar infrastructure. So the British, in one of many elaborate deception gambits they pulled during the war, spread a cover story.

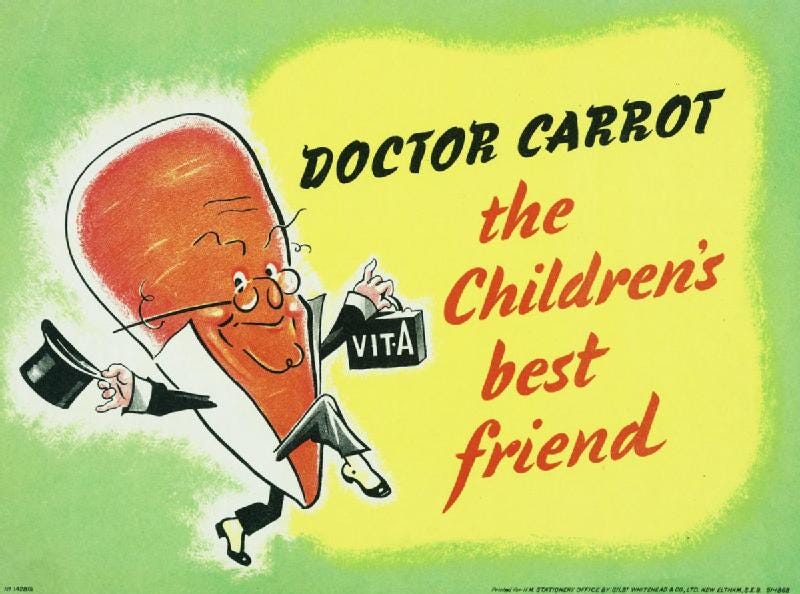

Germans believed that eating carrots improves your eyesight. This is mostly a myth. Carotene, a nutrient and anti-oxidant that carrots have more of than other vegetables, does seem to help avoid the degeneration of eyesight with age. But it doesn’t give you super-vision. That’s a lie the British government promoted in 1940. Actual ace fighter pilots got on the radio and told interviewers that they’d eaten a bunch of carrots, and now they could see in the dark. And, with the help of Walt Disney, they created wartime propaganda, calling on patriotic civilians to grow as many carrots as they could, both to donate to the war effort and to improve their own ability to find air raid shelters. Some of that propaganda was in color, just like Bugs.

So Bugs Bunny in America and Doctor Carrot in Europe promoted orange from “the most common color of carrot” to “the color of carrots.” Non-orange carrots still exist, but they’re a tiny fraction.

Carotene, whose health effects probably inspired the myth that inspired the wartime propaganda, is also what gives carrots their pigment. Current thinking is that that’s not a complete coincidence—our bodies repurpose pigments we ingest to create a sort of natural set of sunglasses, and that’s part of why they help slow our loss of eyesight. So that Dutch trend, starting in the 1600s, of breeding carrots to be oranger? What a happy accident. It improved their medicinal properties, which then maybe even indirectly affected the Battle of Britain.

We see that it’s very consequential that the medieval French word for the color orange happened to sound like the name of the capital of the Provence region. So, how did that come about?

Talk Like A Pirate

Pirates didn’t talk like people do on Talk Like A Pirate Day. All that “yarr, me hearties” stuff comes, like Doctor Carrot, from a collaboration between Disney and the British, in this case the 1950 Treasure Island adaptation, wherein Robert Newton as Long John Silver decided to use an exaggerated Cornish accent. He then got typecast as a pirate for a while, using the same accent each time rather than attempting, say, a Caribbean one.

I mean, I’m sure there’ve been Cornish pirates. But for the most part, historical pirates would’ve spoken in a combination of languages and dialects, taken from their diverse crews and diverse victims. One thing we can guess about historical pirate speak is that they were into rebracketing, the linguistic phenomenon I referenced recently where [Saint Audrey lace] transforms into Sain[t Audrey] lace, then [tawdry]-lace, then finally just tawdry. Rebracketing can happen by accident, when you’re hearing a phrase spoken in a foreign language often enough to learn its meaning, but without knowing where the spaces are. So it’s probably at least a little pirate-driven. Other rebracketed words of interest to pirates include “decoy”, from either the Dutch de kooi (the cage) or the Dutch eendenkooi (duck trap) rebracketed to een denkooi, and “nickname”, from an eke name in Middle English.

Also, pirates were into not getting scurvy. As various sailing cultures have discovered, forgotten, and rediscovered over millennia, if your diet is too low in Vitamin C, your provisions might be easier to preserve during a long voyage, but also your old wounds start to reopen and eventually you die. So pirates, and sailors in general, were very happy when people in Southeast Asia were able to hybridize a sweet-tasting pomelo with a Vitamin C-heavy mandarin. The inventors, who likely spoke Dravidian, called their newly-engineered fruit something like Narantam-K, which became naranga in Sanskrit. It was relatively easy to transport, and, unlike most other fruits high in Vitamin C, it wasn’t actively unpleasant to eat.

As sailors started taking narangas with them everywhere, the fruit, and the Sanskrit name for it, ended up growing all over the world. In English and French, [a naranga] and [une naranga] got rebracketed to a[n aranga] and u[ne aranga]. In languages where the indefinite article doesn’t end with an n, like Spanish, the word tends to still start with an n.

And from the fruit, we got the name for the color. Before oranges, Europeans didn’t have a word for the color, which I think is why we refer to people with orange hair as “redheads.”

It’s therefore very plausible that some unknown pirate mispronounced the name of the fruit to some European locals, and thereby altered history. The words "Arausio” and “Naranja” are probably too dissimilar to have merged, so we’d never have ended up with a city with the same name as a color. So the Dutch might not have standardized on orange carrots, and so on.

(I can’t at all support the claim that it was a pirate, specifically. I just wanted to write about pirates.)

Why Are We Talking About Carrots?

I tell this story a lot. I’ve never really been able to explain why. I think maybe, in a meta way, I’m using it to propagandize my mindset in thinking about history.

No part of what I’ve just written is original research or analysis (although I am just out of frame in that first photo). People have mapped out, speculatively or with confidence, each segment in this path. The only original thing I’ve done here is to join all the segments up, turning it into one long story. A fruit is invented, a word is rebracketed, a city gets a name, a name gets a prince, a prince gets a country, a country gets a color fixation, a carrot cultivar gets into color cartoons. A Vitamin-C-enriched fruit begets a beta-Carotene-enriched vegetable.

Tracing this one line of cause and effect is a blatantly idiosyncratic way to slice up our known body of historical knowledge. But that doesn’t make it wrong. Probably some of the facts in it are wrong, thanks to my own ignorance, errors and omissions in the historical record, and my desire to tell an entertaining story. But the idiosyncrasy of it doesn’t make it wrong. Every historical narrative you’ve read has been written by a human, who chose what to research, what to highlight, and what to juxtapose. They all encode story preferences, biases, and intuitions about how history works. (They all probably have errors too.)

The “why carrots are orange” way of writing history encodes the same kind of thinking as the phrase “an accident of history” does. Your inventions survive your death, but your intentions seldom do. If time is a wall, with the past at the top, history is different people painting specific spots on the wall that they want to paint, and then letting the colors drip down haphazardly and mix together. It’s far from random, but it’s also far from designed.

Diversity of narratives is important. Different mindsets are helpful in different situations. Sometimes a key insight comes more naturally from a progress-centered view of history, or a decline-centered one. Sometimes it comes from a random-walk view, which if nothing else makes it easier to notice when an institution has become pointless. Different narratives also just naturally surface different facts. It’s hard to believe, but as near as I can tell, I’m the only one who’s drawn the parallels with Tromp that I have. They’re obvious once you look, but…why would you look? History’s enormous. Most stories don’t happen to route through that one terrible day in The Hague. And even someone else telling this story might not think it was important to ask why an unusually liberal and republican country ended up so attached to a hereditary line.

Diversity of food is important, too. Monocultures are vulnerable to famine, and man cannot live on bread alone without getting scurvy. Purple carrots get their hue from a higher concentration of anthocyanins, which may have their own nutritional benefits. We standardized on orange, but there’s no reason to make it as nigh-universal as we have. Let’s bring back the carrot rainbow.

Bonus: The Orange Theater

Orange, France has a large, ancient theater that’s still in use, two thousand years after it was built. Thanks to a day trip there last year, and more recently coming across an old French travel guide written by a cricketer, I have some context about why. The Roman Empire saw theaters as a propaganda outlet. In the capitals of their conquered territories, they built stadium-size theaters out of stone, taking advantage of natural slopes. They used them to promote culture, and decorated them with statues of the emperor. (The heads were removable, so when they got a new emperor they could just ship in a new head rather than a whole new statue). So even when they weren’t being used for overtly political purposes, the theaters were still making a statement. “This evening’s entertainment is brought to you by Rome.”

The Orange theater was effective as a symbol of Rome’s power because it was also a practical demonstration of it, built more durably than the locals could build anything. When the Visigoths (and other armies later) raided Orange, the population survived by holing up in the theater. When the Princes of Orange tried to go indy, they tore down most of the theater to repurpose into part of a castle. When King Louis conquered them anyway, his army tore down the castle, and the city gradually fashioned the materials back into a theater, incorporating as many of the original elements as they could dig up.

There’s a reason everything leads back to the Roman Empire. That’s how they wanted it. They built better infrastructure than anyone else, at once awe-inspiring and practical, so that nobody would ever forget the glory of Rome. Plenty of civilizations, Rome emphatically included, used violence for that purpose too. But if you want your name to shine through the ages, there’s no way more effective than to build something useful, and build it tough.

Even though you have told me this story in person, I can't wait to read this!

“That’s all, Folks!” - love it, as I do all your humor. So clever.