Everything in Jamaica is Orange Except Oranges

This article is accidentally not about the election.

There are a lot of Orange place names in Jamaica—Orange River, Orange Cove, two Orange Bays on opposite coasts, a famous Orange Street, and Orange Hill. Why?

Answer 1: Colonialism

Oranges are not native to Jamaica. They were introduced when the Spanish Empire conquered the indigenous Taino, soon after Columbus landed there. Disappointed not to find gold, they tried to make the colony profitable by importing crops, plus enslaved Africans to grow them.

In Jamaica’s climate, oranges are still orange on the inside, but they mostly stay green on the outside—they’re getting more sun, so it makes sense to create more chlorophyll to absorb it. This ended up making them a less attractive export than hoped, because Europeans assumed that a green orange was an unripe or unhealthy orange. And the colonized Jamaicans now often agree. A 2017 editorial in the Jamaican Observer complains that the only oranges you can buy these days are low-quality green ones, which the kids don’t even recognize as oranges. The author calls for more imported American oranges until domestic farmers can “get it right.” Which is a tidy little illustration of the usefulness of decolonizing your mind.

So orange trees existed in Jamaica when these places were being named, but they weren’t ubiquitous enough to really justify that much orange. Also, “orange” isn’t a Spanish word, it’s an English one. So what happened?

Answer 2: Cromwell’s Pirates

In 1655, the English, under Lord Protector Oliver Cromwell, invaded and easily conquered Jamaica, converting it from a Spanish colony to an English toehold in the Caribbean. Most of the Spanish colonists fled, leaving their slaves behind, who fled to the mountains in the middle of the island and formed independent communities.

The English tried importing their own African slaves, but they kept escaping and joining up with the Spanish ones. With such a low effective population, the island appeared vulnerable to a reconquista. So Cromwell authorized a pair of unusual and desperate moves—the colonial government explicitly invited any and all immigrants, and it legalized piracy.

State-sanctioned pirates, called privateers, were an older idea, but Jamaica took it a step further by deliberately becoming the pirate capital of the Caribbean. Port Royal was a true pirate city, with an ethos that was the precise opposite of Cromwell’s Puritan one. Pirates, who lived and died by their reputations, flexed their wealth in the manner of gangsters everywhere. They’d hire strippers—a ship’s doctor wrote that he saw one “give a common strumpet 500 pieces of eight1 only that he might see her naked.” His own captain, he said, would walk down the street spraying everyone with wine, or forcing them at gunpoint to drink it. The town evolved to make “pirates showing off their booty” central to its economy. A missionary showed up, declared the place “the Sodom of the New World,” and noped right back onto the ship he’d sailed in on.

And indeed, in an unusually heavy-handed divine intervention, an earthquake in 1692 tipped the entire city into the ocean.

So Cromwell is why Jamaica got English place-names, and pirates are in large part why they stayed English. And pirates did like oranges, to prevent scurvy. So this is a large part of the story. But it leaves two big questions unanswered. Why so many orange place names? And how and why did Cromwell and the English do all this?

Answer 3: The Jews, probably

That’s the argument of an entertaining history book, The Jewish Pirates of the Caribbean by Edward Kritzler, which is also where I got the anecdotes in the last section. Jewish history, Sephardi in particular, is all about trying to not be in areas controlled by Catholic Spain or Portugal, where being Jewish meant you had to practice in secret, and were in constant danger of a horrible death at the hands of the Inquisition. This was a difficult goal, seeing as how Spain and Portugal, in a negotiation mediated by the Pope, had each agreed to colonize half of the world.

Kritzler gives strong, though far from definitive, evidence that the decision to conquer Jamaica was influenced by Jewish spies and crypto-Jewish advisors close to Oliver Cromwell. Crypto-Jews in Jamaica had sent word to their allies in London that they were in danger of a Spanish purge, and also that Spanish defenses there were quite weak.

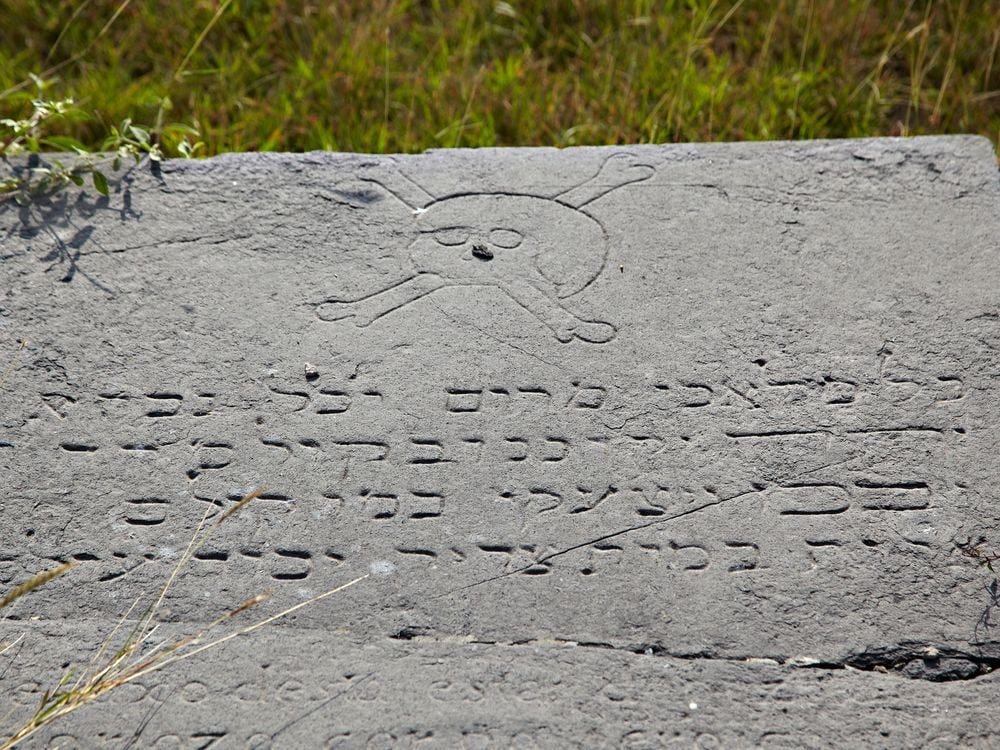

Jews were also closely connected to the region’s pirates. Mostly, this meant fencing their stolen goods, but they weren’t always just middlemen. Some were also financing them, hoping to build up a fleet to conquer a new homeland for the Jews (Chile was one idea) in the name of some non-Catholic European power. And some were straight-up pirates. There are grave markers in Jamaica with Hebrew lettering and the skull-and-crossbones.

With Cromwell’s “connivance,” as an irritated anti-Semite put it, Jews became a visible and active presence on the island. During the age of the pirate economy, their pre-existing relationship with the pirates meant they effectively had monopolies on a good chunk of the country’s trade.

Things got a bit worse for the Jews when the English monarchy was restored. While Charles II reneged on a promise to return Jamaica to the Spanish, he was more open than Cromwell to Christian merchants’ pleas to break the Jewish monopoly on pirate booty. The governor of Jamaica tried to talk him out of it, writing in 1671 that the situation was perfect as-is.

To keep up the credit if not enrich the island, His Majesty cannot have more profitable subjects than the Jews. They have great stocks and correspondence; His Majesty cannot find any subjects but Jews who will so adventure their goods or persons to get a trade. Their parsimony enables them to sell the cheapest; they are not numerous enough to supplant us; nor is it in their interest to betray us. Hopes we will do as much as will keep up the credit if not enrich the island by keeping peace and obliging them.

—Governor Thomas Lynch, quoted in Kritzler.

Charles ultimately refused to expel the Jews, but he did revoke many of their licenses to trade. He was no Torquemada, but the situation still seemed a bit precarious. Things got worse when Charles died without an heir, putting his Catholic brother James on the throne.

With disaster clearly imminent, the Jews took an even bolder step. They financed what came to be called the Glorious Revolution, replacing James with a strong opponent of Catholic imperialism: William of Orange, who’d become the ruler of the Netherlands after a plot with his ally Tromp to end the republic.

Answer 4: Orangism (and therefore also the Jews again)

The Eighty Years War, in which another William of Orange won Dutch independence from Spain, created the color symbolism that caused carrots to become orange, but it also changed2 the symbolism of orange, and oranges, throughout Europe.

The symbolism was a bit complicated because it depended on your preferred narrative about the Eighty Years War. It was a war of independence, so orange could be the color of revolution. It was a war that created a line of hereditary rulers, so it could be the color of royalism. It was a war where Protestants beat Catholics, so it could be the color of Protestantism. This last one was the most popular in England.

What almost everyone could agree on, though, was that orange was the color of not being conquered by Spain. So even though Spain had introduced oranges, it seems safe to say that Jamaica named places “after the fruit” as a reference to the one common interest among the English, Africans, European Jews, and pirates living there. In some cases, people may even have named their estate in honor of the now-English king granting it to them.

The Princes of Orange had deep connections to the Jews, due to their influential presence in Amsterdam. For one relevant example, in 1616, Maurice of Nassau, a future Prince of Orange, joined the funeral procession for Samuel Pallache, nicknamed “The Pirate Rabbi.” Pallache, whose Hebrew name was Shmuel Palache, indeed had rabbinical training, but bucked family tradition to become a merchant, diplomat, and, yes, pirate.

So it’s not too weird that the Glorious Revolution was brought to you in part by a large zero-interest loan by Jewish financier Antonio Lopes Suasso. Jews had recognized for a long time that their ideal ruler in diaspora was either Muslim or Protestant. Muslim was probably a bit better (there’s a reason Pallache is wearing a turban in that portrait), but installing a Muslim ruler of England would’ve been tricky.

Ephraim Nissan, in a delightful paper, argues that the presence of an orange in a comedic Jewish folktale started out as being about the House of Orange, and in particular about Catholic concerns about a Jewish/Protestant alliance. In an old Sephardi variant of the story, it’s the Pope who, for reasons that are never explained, demands that a representative of Rome’s Jews debate him in pantomime, with dire consequences if they lose. Reasoning that a pantomime debate is mostly about optics, the Jews decide not to send a rabbi, but an imposing-looking blue-collar Jew. They then proceed to have a pantomimed debate where each side misunderstands the other’s symbolism. This includes a moment where the Pope pulls an orange out of his pocket and offers it to the Jew. The Jew shakes his head, pulls a matzoh cracker out of his own pocket, and eats it.

The Jew parsed that exchange as the Pope condescendingly offering him a snack, and him refusing it in an emphatically Jewish way by eating matzoh. What the Pope thought was going on has evolved over time, but Nissan argues that we’re meant to understand the exchange from his holiness’s point of view as “You Jews are all Orangists (meaning aligned with the Protestants), aren’t you?” The Jew responds with a communion wafer, meaning “No, no, we’re pro-Catholic.”

At the same time, Jews in England were starting to be associated with oranges. Selling citrus fruits in the street was a job you could get without being respectable or well-connected, so orange-sellers were often marginalized people of one sort or another. Under Charles II, they were typically prostitutes, using orange sales as a side-hustle and excuse for being alone with men, or former prostitutes looking to go legit. Nell Gwyn, one of the biggest celebrities of the era, got her start as an “orange-girl” in a theater, employed by a former prostitute, Mary Meggs, nicknamed “Orange Moll.” Samuel Pepys’s diary, a key source on this period, has three different mentions of this entrepreneur. In one entry, Pepys sees Orange Moll talking with Admiral William Penn, who’d just come home after leading the conquest of Jamaica, so we can add another piece of string to our conspiracy board.3 In another, he witnesses her saving the life of a gentleman choking on a piece of fruit. Selling oranges was an entry-level job, but it wasn’t exactly unskilled labor.

After the prostitutes came the Jews. They would later be supplanted by the Irish, followed by gay men and trans women. These last lived in what they called Molly houses, in tribute to Orange Moll and her ilk, and took names like Orange Mary and Pomegranate Mary.

But all of that was still to come. For a long time, Jews monopolized the orange-selling trade in London. “Jew orange-boys” were sometimes considered a nuisance on the street, or used as stock characters in fiction. An 1827 essay satirically, and prophetically, pretended to take great offense at the Jewish monopoly on citrus sales, saying that every Irish immigrant should be given free oranges in order to undercut the Jews, while slipping in a pun or two on Orange-the-ideology. The expression “light as a Jew’s orange” shows up in a serial novel in 1851.

And, in the former British colony of Jamaica, there is an Orange Street Jewish Cemetery.

All of the above, and more

I don’t think any part of this narrative is a pure coincidence. People rarely put their thinking into writing when naming places, so I don’t think we know exactly what went down, but I think it’s very likely that the name Orange outlived the presence of actual orange trees because people liked its associations. And while it’s very possible the Jewish influence on parts of this is overstated, it was definitely a factor. So, yes, places in Jamaica being named Orange can be traced back to various English, Jewish, and pirate schemes.

But the narrative is also a result of my ethnocentric choices in which parts of this story to research. I think it’s quite likely someone else would’ve credibly written this as an Irish story, or an Afro-Jamaican story, or something completely different. History is big and complicated. There’s room for a lot of legitimate stories about the same thing.

Which is why I want to come back again to my first answer—colonialism. Green-skinned oranges can be just as good as orange-skinned ones, but if your dominant culture is based in colder climates than yours, you can end up seeing your local ones as primitive, shoddy, illegitimate. You end up paying extra to import oranges from Florida when you could grow them yourself. It’s a tiny part of how the oppressive systems of the past contribute to inefficiency and inequality today.

History works the same way. When we make everyone studying for the SAT learn that Georgia was first settled after North Carolina, we’re not exactly lying to them, but we are definitely cheating them. We’re framing everything, in an unconsidered and implicit way, the way English people hundreds of years ago decided to, to make themselves the protagonists of the story. Everyone is entitled to a version of history that centers their own heritage, that gives their own people agency. Not their own facts, but their own perspective, their own choices.

I meant for this article to be about the election tomorrow. Here’s why. Kamala Harris’s father, an influential economist, grew up in Orange Hill, Jamaica. He and his other daughter Maya both remember how bold Kamala was when she visited Orange Hill as a small child. He writes:

Upon reaching the top of a little hill that opened much of that terrain to our full view, Kamala, ever the adventurous and assertive one, suddenly broke from the pack, leaving behind Maya the more cautious one, and took off like a gazelle in Serengeti, leaping over rocks and shrubs and fallen branches, in utter joy and unleashed curiosity, to explore that same enticing terrain. I quickly followed her with my trusted Canon Super Eight movie camera to record the moment (in my usual role as cameraman for every occasion). I couldn’t help thinking there and then: What a moment of exciting rediscovery being handed over from one generation to another!

Dr. Harris sees his cultural heritage the same way, as something each generation should get a chance to excitedly rediscover. I agree. This is the vibe we should have when first learning history—children exploring, at their own rate, following their curiosity, while adults stand back and watch, ready to help but only if they get stuck. Everyone should get to find their own path through Orange Hill.

Something like $25,000.

Previously, the fruit had sometimes been used as a punning reference to Portugal, because in what appears to be a coincidence, purtuqāl (from Iraq) is an Arabic word for orange. See Nissan, “The Pantomime of the Orange and Unleavened Bread in a Judaeo-Spanish Folktale”.

I’m not going anywhere with this, but if you come up with an Orange Moll/William Penn conspiracy theory, please share it.

I come away with a few thoughts. One: Jewish Pirates! I love the gravestone. Two: Colonialism is the root of so many of our problems, and the green orange would make a great symbol of that. Somehow. Maybe you'll figure out a way to make that a button or a banner. Three: I can't believe Harris didn't beat the con man. Maybe it has to do with his orange hair. Not funny, I know. Too tragic to be funny.