When I see a rule posted somewhere, I have an irresistible urge to interpret it in ridiculous ways. They, the “They” who write rules, are claiming authority over me, you see, but I can reclaim it by demonstrating that they wrote them badly. I’m a stickler on language, but only when it’s the language of authority. (Meaning I can [stet] write however I want1 because I’m not the boss of you2.)

Regular readers may remember discussion of Louisiana enacting Mormonism as their state religion, California banning all materials related to critical race theory, and the SAT II asking some really hard questions. More seriously, I’ve mentioned how I feel like you really shouldn’t indict someone for assault with a sharp object if the alleged attack was with a blunt object, which is apparently a minority point of view.

If I set aside my very strong intuition, though, it’s not really obvious that I’m right as a matter of political philosophy.

Take this sign in the park near my house. When I photographed it, I was a dog owner who didn’t have my dog with me. Doesn’t that mean I was breaking the Village Code? It doesn’t say “or leave the dog at home,” does it?

But it does, actually, add in that important exemption in the official Code. Just in a verbose, detailed way, so they left that part off the sign. That’s probably why there’s no period after “length,” because if there were it wouldn’t be a valid excerpt. (The actual continuation starts with “, except”). They weren’t trying to get away with anything here, just saving on sign space.

Even so, the official Code forgot to include the exception where you’re in the village, but your dog isn’t. Which sucks, to be sure, but doesn’t really deserve a $250 fine.

I’m pretty sure nobody would ever fine me in New York for being a dog owner whose dog is off leash in Pennsylvania. But at some point, this does start to matter.

For example, was it illegal for me to take that photo? The same Code is pretty emphatic about no filming without a permit, and their definition of filming is broad enough to include taking a photo with your phone. Honestly, it’s broad enough to include me typing these words right now in my own living room. Yikes. That’s a loophole a sufficiently-annoyed local authority could take advantage of.

Here, the vagueness is kind of getting away with something. The intent of the law is more like “you can’t be disruptive to create content unless you warn us in advance and give us money.” It all works better when the Law gets to be subjective in how it judges annoyance, and selective in whom it charges for a film license.

Attorney Harvey Silverglate has claimed, dubiously, that the average American commits three felonies a day, in the sense that if a federal agent wanted to charge you with a crime, they could interpret the law that way without getting laughed out of court. For example, it’s illegal for drug manufacturers to advertise any use that hasn’t been FDA-approved. You might think this is only a problem for drug manufacturers, but suppose you personally recommend an off-label use of a drug, and suppose you’ve ever received anything free from that drug’s manufacturer. (For example you are any doctor.) Well, now you’re in a conspiracy with the manufacturer to illegally advertise, if it would be tactically helpful to the prosecutor. This is not a hypothetical example, although it’s a legitimate gray area.

There’s a pretty fundamental problem here. If we want to ban a specific entity doing a specific thing, we need to be able to prosecute them for paying someone else to do the thing, or else the ban is meaningless. And we need the concept of a conspiracy. Otherwise organized criminals can make their power structures illegible enough that no one person has clear responsibility for any serious crime. And we need the boundaries around these concepts to be a little fuzzy or else people will skirt just past them and defeat the intent. All of which adds up to saying that we need to give the legal system some wiggle room.

On the other hand, that’s handing the law the ability to abuse the wiggle room. Embarrassed that you arrested someone for possession of what turned out to be harmless bacteria in a petri dish? You get “creative.” Did the people who ordered the bacteria tell the lab they were going to transfer them to the perp? Okay, yes, they did inform them, but only after transferring. Which is in accordance with the lab’s policy, sure, but it still means they ordered the bacteria under false pretenses. Conspiracy to commit mail fraud! (Real-life example from Silverglate.)

One might be tempted to give up on the concept of the “rule of law” altogether.

Every Case is a Rule To Itself

Philomena Cunk, BBC: Who was Ron?

Professor Gregory Dart, chair of the Hazlitt Society at University College, London: Among the Romantics, you mean?

Cunk: Yeah.

Dart: William Godwin was quite wrong. He believed that there should be no laws at all in society.

Cunk: No, who’s Ron?

Dart: Ron? Ah, is there a Ron?

Cunk: Yeah, the one that wrote all the poems and signed them By Ron.—Diane Morgan, Cunk on Britain (Cunk is a character played by Morgan, Dart is real and playing along)

Nobody could ever be as wrong as Philomena Cunk, but Dart is a bit wrong himself. For one, it’s stretching things to call Godwin a Romantic—the movement took inspiration from him, and had close ties (Godwin’s stepdaughter had a child by By Ron), but his vibes were more like the Enlightenment-era philosophers the Romantics were reacting to.

For another, it remains the position of this blog that William Godwin was right about everything (except for the things he was wrong about).

Dart is quite right, though, to say that Godwin believed there should be no laws at all in society. Oh, Godwin still thought there should be policing, trials, and penalties for crime. He just didn’t think we should try to define what was illegal and what the penalties were.

In his Enquiry Concerning Political Justice, Godwin argues that legal codes have failed as soon there start being trials. The purpose of codified law is to make it unambiguous, in advance, whether a given action will be legal. But if a case goes to trial, that means both sides think they have a chance of winning, so there’s demonstrable ambiguity even after the fact. Either people have different expectations about how the rules of evidence will be interpreted, or they disagree about whether the allegation constitutes an actual crime.

The actual effect of laws, he argues, is pernicious: it hides the agency of the lawyers, judges, and jury. A corrupt judge can pretend to be simply enforcing the law as written. An honest lawyer (whose existence he considers purely theoretical) is honestly surrendering his own agency to a legal code that becomes outdated before the ink dries.

Without laws to hide behind, corrupt judges would be easily exposed—they’d have to own every unjust decision they made. And juries would recognize just how much responsibility they had—they’re not there to follow the rules, they’re there to determine the will of society in this specific matter. Which is better, because every case is unique, “a rule unto itself.”

He has a point. Some cases need to be decided by singing contests, according to a 1902 issue of Camp and Plant, a periodical about the lives of steelworkers and their communities. Eliza Ragland, a Black woman living in Peppersauce Bottom (the moonshine district of Pueblo, Colorado), had a White neighbor whose name was not Karen, but whose favorite pastime was lodging complaints against her. The latest was that she had caused a “disturbance” by singing “I Don’t Want No Hoodoo Hangin’ Round,” a song about chasing off a witch who’s trying to curse you. Ragland proved her innocence on the witness stand by singing the song “with which it was alleged she had made the night hideous,” demonstrating that she sang “unusually well” and therefore was not causing a disturbance. (She also indicated via body language exactly which witch she didn’t want hanging around.)

Why bother even trying to define “disturbance” in a law, if it can be a question of music appreciation? Why not just have the accused do the thing in court and decide whether it’s disturbing?

(One issue that Godwin doesn’t go into is that we might need better protections against frivolous arrests. But we need those anyway.)

Is it ethical to sign a poorly-worded document?

He was remembering a house lease in Professor Orlock’s class. “What it amounts to, in English,” Hagbard had said, “is that the tenant has no rights that can be successfully defended in court, and the landlord has no duties on which he cannot, quite safely, default.”

Shea and Wilson, Illuminatus!

I’ve signed a lot of things where a more principled person would’ve refused. My last lease had this clause:

12. Alterations by Tenant.

Tenant shall not: (i) make any changes or alterations to the House in any way, including wallpapering, painting, repainting, staining or other decorating;

…

Further, without Landlord's prior written consent, Tenant shall not install or otherwise place in the House … any other equipment requiring connection to the electrical or plumbing systems of the House (collectively, "Appliances").

I had no intention of literally obeying this clause. I had a TV that needed to be plugged in, and a few decorative refrigerator magnets, and I wasn’t going to get written permission first because I knew Landlord didn’t construe it as required. So I was kind of being dishonorable? But I knew how it’d go if I objected—the landlord would condescendingly explain the intent of the clause and refuse to alter the wording.

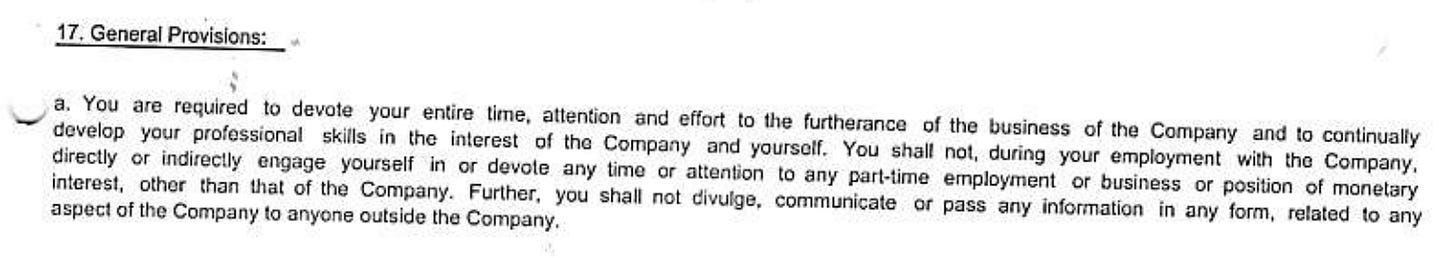

Similarly, I’ve signed so many employee handbooks and similar documents with clauses I knew I couldn’t obey. I’m not going to post them, but these are some very similar ones I found online:

I signed these, of course, because of a power imbalance. What was I going to do, walk away from a lease or a job because of a little unenforceable language? And I think that’s ultimately what a lot of poorly-written rules are about—they’re exercises in dominance. “You think you have legal rights as an employee? Leverage? We can make you sign a blank check and keep it on file for as long as we want.”

Poorly worded rules are weaponized incompetence.

Or Sometimes Just Regular Incompetence

The Texas Constitution accidentally says that the state can never recognize any marriage.

Florida considers anything that contains any quantity of tyramine to be a controlled substance, which amounts to a total ban on cheese, chocolate, and humans.

Virginia’s traffic code says that you’re not allowed to ever be driving your car next to another car unless you’re “overtaking and passing” them, implying that all drivers traveling in the same direction and separate lanes are obligated to race each other.

I don’t think any of these are likely to be fixed any time soon. They’re more likely to patch loopholes in the other direction—once Missouri accidentally downgraded all theft from felony to misdemeanor, but they undid that one pretty fast.

I think I mainly find this stuff creepy because a carefully-worded law is a proof of work. Florida making cheese a controlled substance is a signal that they’re not interested in thinking carefully about their drug policy, and therefore they’re likely to have made more consequential mistakes. Texas banning marriage shows how unprincipled their legislators were in trying to ban gay marriage—they only cared about the gesture, not the consequences.

If you see a sign like this, definitely don’t enter.

Unless I’m writing in Go or Java. Ruby’s still pretty “anything goes.”

I may or may not happen to be the boss of you as you read this, but I am not acting in that capacity while writing it.

This is so aptly timed! Zak and I are dealing with the real life consequences of an outlandishly worded rental contract right now.