I turn 39 today. My present to myself this morning was to search in Google Books for profiles of thirty-nine-year-olds of the past, with an eye towards writing a Whig-inflected post about their roles in history. I got pretty lucky: the first result was a 1919 article in The American Magazine’s “Interesting People” series, where they did some detailed profiles of non-celebrities. The 39-year-old in question, insurance sales manager Bill Bilheimer, is about as Whig as they get.

A Born Booster

Bill Bilheimer, reports author Grace Reeve Fennell, was “one of the best known and best liked men” in Saint Louis, Missouri. Since his main skill set was being charismatic and outgoing, he turned to insurance sales to make a living, and ended up making a comfortable one. Enough that in his spare time, he could do a kind of pro-bono salesmanship, as a “booster” for various causes via speeches and advertising. I’ve followed up on two of the examples the article gives: the creation of the original Knothole Gang and saving the State Commission for the Blind.

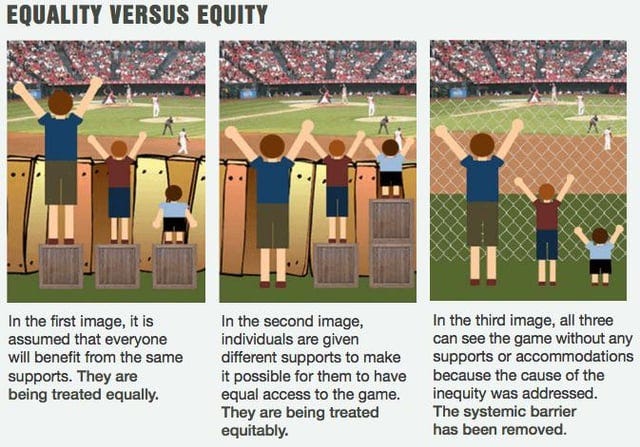

“Sow dollars, reap men” was his slogan for the first of these campaigns. What other people thought of as charity, he thought of as investment. Help people get their start, and they’ll end up being more successful, therefore paying more in taxes and making the city richer.

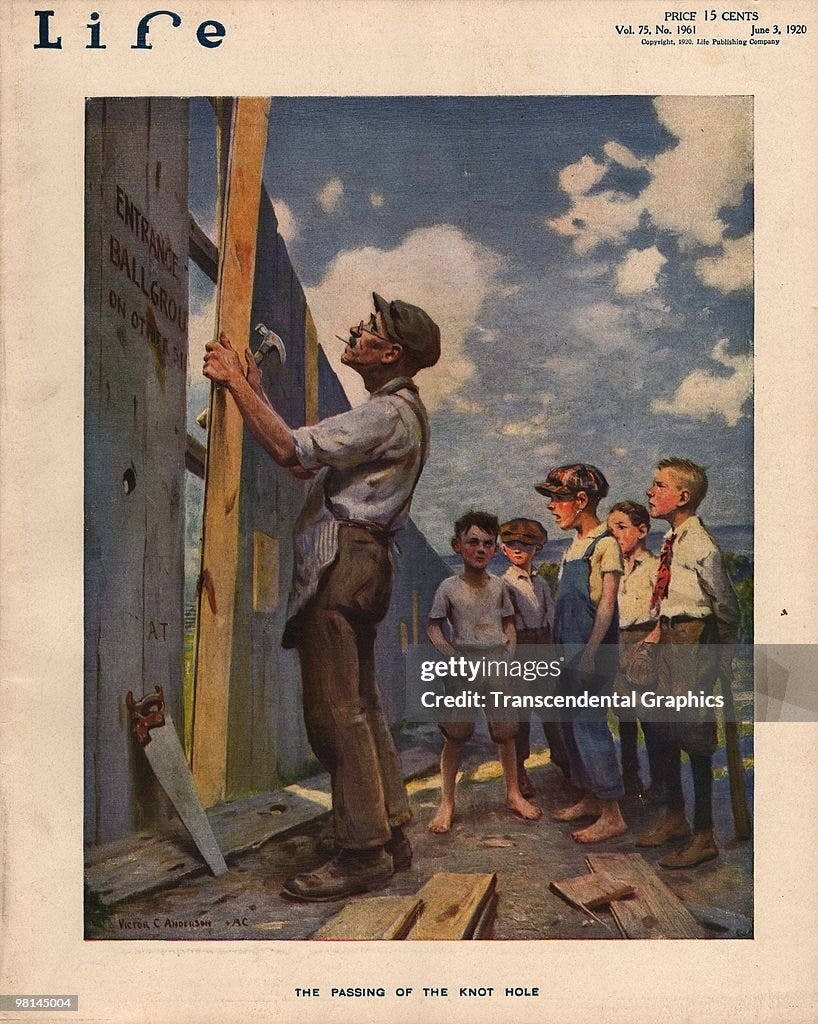

The Knothole Gang

I’ve used this cartoon before—it’s one of my favorites.

The more common image of kids trying to watch a baseball game when they can’t afford tickets has them peering through knotholes in the fence.

Especially before TV, it was a real problem that professional sports were too expensive to be the popular entertainment they were meant to be. Bilheimer helped conceive and promote a more stable solution: the St. Louis Cardinals were bought by the city, with shares available to the public. Each share came with a season ticket—not for the shareholder, but for them to give to anybody they spotted watching the game through a knothole. Kids with these tickets often got to meet the players, or be recruited into Little League and its precursors. The program was emulated nationwide.

Kids getting to watch baseball is a worthy end in itself, but sports are also an engine of economic mobility. Children who couldn’t afford a ticket got the opportunity to discover a life-changing talent. I’ve traced one of them, the illustrious Joseph Jaeger.

Joe Jaeger was born in 1919 (the year Bilheimer turned 39) to two Hungarian immigrants and grew up in St. Louis. He was one of the early members of the Knothole Gang, got a chance to learn how to play, and ended up going to the University of Wyoming on a baseball scholarship. There, he discovered his true passion: conservation. He earned a degree in forestry before his academic career was interrupted by World War II. He joined the “Ski Troops,” an army regiment training to use skis in mountain combat. The ski troops were mostly deployed to the mountains of Italy (coincidentally, this includes my spouse’s grandfather, who probably trained with Jaeger). Jaeger, though, was deployed to the Aleutian Islands, and was injured helping to repel the Japanese invasion of Alaska.

After the war, he had a long career heading projects for various park services. This included a stint in Jordan. I assume that’s when he was photographed wearing a keffiyeh. While there, he rescued one of my favorite things in the world from obscurity and decay: the artificial oasis and castle hewn from rock, known to its creators as Raqmu and now to the world as Petra.

Most of his work was in the United States, and in particular Missouri, where he championed innovative projects such as the Elephant Rocks State Park Braille Trail, a hiking trail designed to be accessible to people with vision impairment and other disabilities. He’s also credited as one of the creators of the Lake of the Ozarks Community Bridge, which just became free this year, 18 years ahead of schedule, thanks to an evidence-based toll and financing system called out by the Center for Innovative Finance Support at the U.S. Department of Transportation.

Jaeger would probably have done fine without Bill Bilheimer’s scheme, but it sure seems to have helped to have gotten that baseball scholarship. Without it, maybe he wouldn’t have gone to college until after the war, like a lot of his generation. Maybe, with a slightly later start, he’d have done all the same things except the bridge. That’s a pretty good return on investment, right there, for Missouri. One free season ticket to the Cardinals, and a few decades later, you get a free public bridge!1

And that’s just one kid from the Knothole Gang.

Friendship, Not Charity

I also looked for some beneficiaries of the Missouri State Commission for the Blind, to which Bilheimer donated some effective advertising to raise donations. David Krause was one. Here’s Senator Morgan Moulder (D-MO), speaking in committee in 1959:

Missouri today has an advanced unique form of aid to the blind. It is unique in that it is geared to rehabilitate. The monthly aid check is intended as a helping hand to enable blind persons to become totally self-supporting, not a heavy hand to keep them forever doomed to live in poverty.

…

Mr. Krause, who has been totally blind since childhood, was born and raised in Missouri. For several years he was a recipient of aid to the blind in my State. Today however he is no longer on aid. He is now a taxpayer and not a tax consumer. He is presently employed as a regulations officer, Department of Occupations and Professions, District of Columbia government.

The basic idea behind Missouri’s “advanced form of aid” came from the blind lobby, and I agree it should be the standard for public disability support. Unfortunately, it isn’t. With most programs, if you get a job, either you lose your support entirely or it’s cut enough that you’re not netting any more money than when you were unemployed. Having too much in savings also gets you kicked off. This stringent means-testing has the unintended consequence of making “becoming self-sufficient” a risky process, where you can easily end up worse off if you get unlucky, while staying unemployed forever can seem comparatively safer. Missouri’s aid simply relaxed the means testing, so that your benefits weren’t cut at all until you were financially secure.

Thus, Krause was able to pay back Missouri’s investment in him. He also became a national advocate for the blind, focusing in particular on giving them opportunities to give back. Compound interest. Here’s something he wrote for a St. Louis newspaper, republished by the Braille Monitor in 1958:

In short, a blind person really wants friendship, not charity. And there is a great difference. Charity is a one-way street, where one gives and the other receives; friendship is a two-way street, where both parties give and both parties receive. Let me illustrate my point. Say that your next door neighbor is a blind person. If you are constantly doing little favors for him but you never think of requesting favors in return, then you are giving charity, not friendship. When a blind couple double--dates with you and your wife, do you feel an obligation to pick up the check? Do you flatly refuse any attempt on the part of the blind people to pay their share? If so, and unless you are one of those rare individuals who always picks up the check with your sighted friends too, then you are not giving your blind associates a fair shake. Again, it is simply a case of charity, not real friendship. To be sure, I know there are some blind people who are quite happy if a sighted friend will always pick up the check, but after all, how many sighted people do you also know who are chronic "freeloaders?"

The Parable of the Booster

I really like Bill Bilheimer’s metaphor of “sowing dollars.” Sowing crops isn’t deterministic, it’s statistical. Some of your seeds are definitely going to fail, and some will grow into something you don’t get to harvest, for one reason or another. You might lose an entire crop sometimes, but usually, you can expect to reap more than you’ve sown. Johnny Appleseed was a genuinely kind soul, who planted seeds out of altruism, but he also found it pretty easy to turn a profit, by buying up small parcels of land where he hoped his trees would grow.

I wish more of our conversations about public projects involved a projected rate of return. Not everything worth doing is going to be profitable, even in the broadest sense, but almost everything is. When we talk about whether to keep funding some government agency, we talk about it like we’re putting money in and getting services out, and debate whether the services are worth the money—but that’s (sorry) an apples and oranges comparison. The input is money now. The output is money later. In the middle, sure, you’re helping poor children and blind people. But you can measure how well you helped them by how much they end up giving back. Increases in expected taxes are a decent proxy for measuring impact, and a usefully quantitative one.2 It’s as vulnerable to Goodhart’s Law as any other measure, but at least if you over-optimize on it, you’re still increasing tax revenue.

It might seem a little cold to talk about aid to the needy like a business investment. But I think it’s ultimately more respectful than calling it charity. Like Krause says, if you don’t expect your blind friend to pick up the check every so often, you’re not quite seeing them as a full person. People, on net, create more than they consume. Sometimes, they just need a little extra boost first.

Bilheimer, like most of the donors he wooed, didn’t expect any particular personal benefit, aside from direct ones like people liking him more. But he didn’t see his work as charity; he saw it as giving solid business advice to society. Another favorite metaphor of his, the article says, was that it’s cheaper to put up a guardrail than to let people fall. Which is not universally true, but tends to be a good heuristic.

I haven’t actually done an economic analysis of these two interventions, because again, researching and writing this article is my birthday present to myself. But I think it’s pretty telling that one of the original Knothole Gang kids ended up building a hiking trail for the blind. I didn’t go looking for anything like that, I just stumbled onto it. If the first two ripples you look at are ones that collide with each other, that’s a sign that the ripples went wide.

It’s been a comforting exercise, sampling the impact of a guy my age, on a day when I tend to look back at my life so far with an appraising eye. There’s no Wikipedia page for William Edward Bilheimer. I doubt Krause knew his name, and maybe not Jaeger either. But he did enough for immortality. He helped people who helped people who helped people who are helping people who will help people, and so it will be for as long as there are people. I think that’s a worthy life. I don’t know, and may never know, which of the seeds I’ve planted, dollars and time I’ve sown, will grow, and what they’ll grow into. But I have faith. Because y’all are awesome.

More or less free from the state’s point of view, too—thanks to that innovative financing model, it was paid for by private investors, who also profited.

To decide whether it’s better to help 100 blind adults get jobs or 500 kids have better childhoods, you need to do philosophy. To decide whether it’s better to get $300,000 ± $25,000 in four years or $2,000,000 ± $500,000 in twenty years, you can do math instead. Math is generally preferable to philosophy.

I like your birthday gift to yourself! Interesting piece, as always!

Happy birthday!