To broaden access to higher education, make it cheaper to provide.

Like, you know, everything else.

Let’s play a game. You’re running an elite private college. Here are some contrived dilemmas you might face.

Q1: You receive a generous donation from an alum, but it’s restricted. You can only pick one of these three ways to spend it, in perpetuity:

A - Expansion. Increase your total enrollment capacity by 10%.

B - Financial Aid. Allow students to spend an average of 10% less on tuition.

C - Bonfire. Every year, make a giant pile of cash on your quad and burn it to ash while students sing your college anthem.

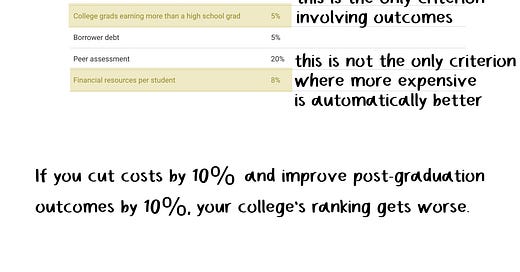

Each of these options has advantages and disadvantages. Expansion lets you serve more students, but the only way to admit more students is to become 10% less selective, which hurts your prestige. For example, your U.S. News and World Report ranking would worsen—colleges don’t gain any points for having more students, but 5% of their ranking is determined by how good their incoming students’ SAT scores are.

Financial aid is significantly better for your prestige. The amount of debt students graduate with is weighted at 5%, just as much as their starting test scores. The main downside is that your average graduate will likely be less wealthy and successful, which could harm you in the future. While an elite college degree can improve your economic outcomes, having parents rich enough to pay full price for an elite college also improves economic outcomes.

Finally, we come to the bonfire. You’d think this would be neutral in its effects, but not when it comes to quantitative rankings. You’d be increasing the amount of money spent per student by 10%, and that metric is weighted at 8%. So this option is the best as far as rankings are concerned.

Q2: The board has noticed that you have two very similar pre-law programs, and tells you to eliminate one to save costs. They cost about the same to run, so you can pick which one. Students seem to do just as well in each, in terms of postgraduate outcomes. The Seminar Program involves lots of quality time with your professors, while the Lecture Program involves large class sizes and significantly greater capacity, so you’ve been choosing who gets into which program via lottery. Usually about 10% of interested students get into the smaller program.

Which one lives and which one dies?

One way to look at this is to say that the Lecture Program is clearly more cost-effective. It’s serving nine students at the same cost as one in the other program, and they’re doing just as well.

The other way to look at it is that cutting the Lecture Program will decrease your student-faculty ratio, increase your financial resources per student, and probably lead to you hiring more faculty since the Seminar Program will need to expand to cover the gap. All of these changes will improve your school’s rankings and prestige.

Colleges aren’t run by robots programmed to maximize U.S. News and World Report rankings. They’re run by idealistic humans, who want their institutions to actually benefit society. Sometimes those humans will make choices that lower their ranking, or similar measurements of prestige. Then, either they get fired and the institution course-corrects, or the institution stays the course and falls in the rankings year after year. The degree becomes less prestigious, attracting less talented students, and eventually you don’t count as elite anymore. The elite colleges are the ones that continued to sacrifice children to Moloch.

How accurate is this model? According to howcollegesspendmoney.com,

At private institutions, whose average undergraduate enrollment was 2,619 and average tuition and required fees was $34,508, a 0.5% spending increase per student is associated with the equivalent of one additional graduate at the cost of $53 in tuition.

To scale it up to match my hypothetical 10% spending increase above, the average college would spend it in ways that allowed 20 more students to graduate, an increase of less than 1%. So that’s a negligible portion going to expansion and financial aid.

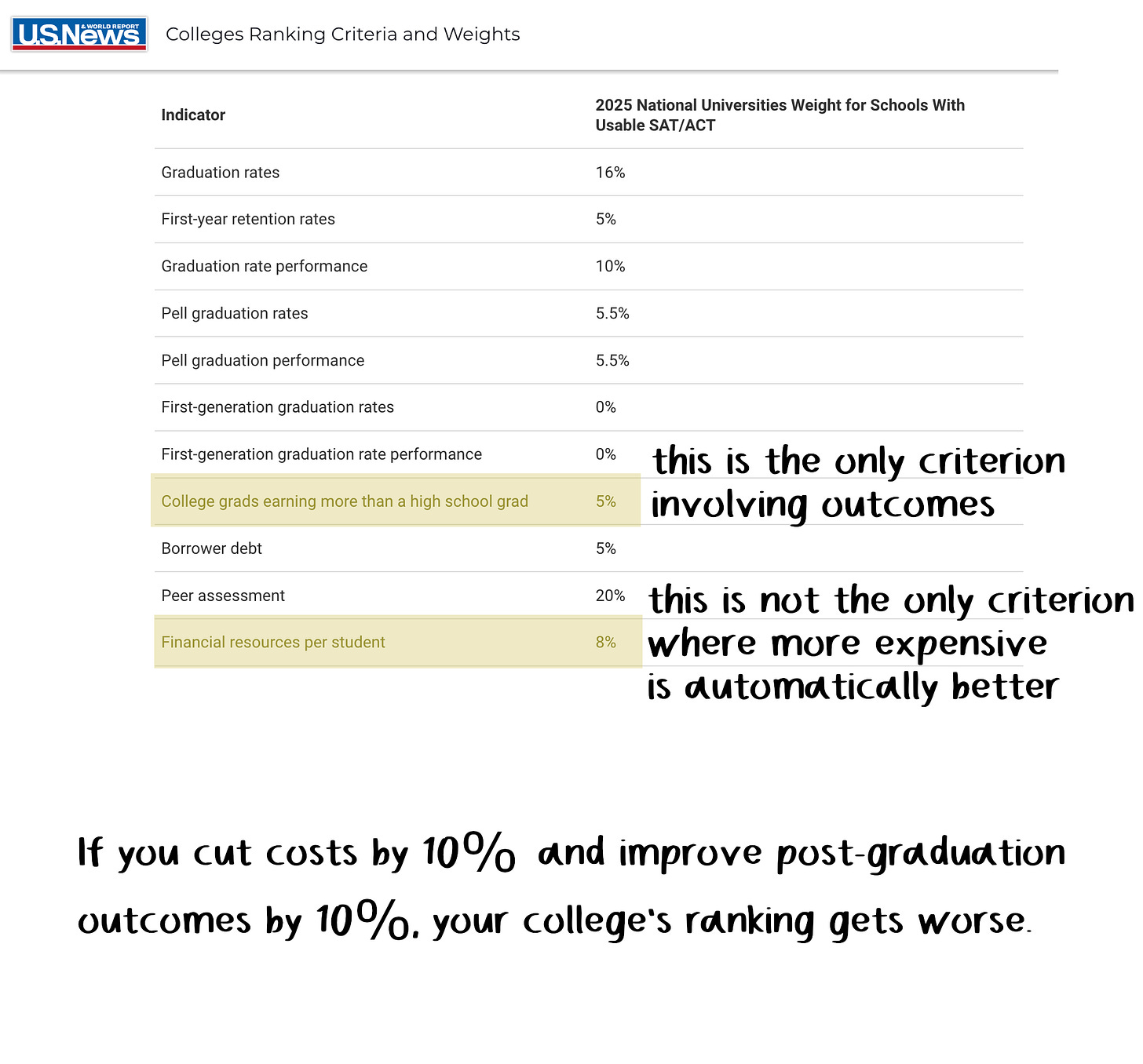

Maybe more money tends to go toward giving raises to faculty? For those of you who didn’t just laugh bitterly, no. This is not happening.

And yet colleges are spending more and more money—tuition costs typically increase more than inflation each year. So, when you’ve eliminated the impossible, whatever remains, however improbable…

Admittedly that’s AI art and not reality. Colleges aren’t choosing Bonfire exactly—they’re choosing Other.

Maybe that “Other” is necessary? Is good education inherently getting more expensive? That would be pretty weird. In a world with YouTube and Wikipedia, every way of learning other than formal education has gotten much cheaper. Why would the cost of providing a free online lecture series go down while the cost of providing an accredited one goes up? More likely, colleges are mainly spending money to keep their quality level steady, compensating for the never-ending tweaks they’re making to be less cost-effective.

Colleges do occasionally try to do a fake bonfire and sneakily spend their money on beneficial causes, but that only works until you get caught. In a recent scandal, Columbia University was caught red-handed spending over a billion dollars on providing medical care for patients in hospitals, while claiming they were spending it on education. Now that their own Dr. Thaddeus, whom the media calls a whistleblower but I’m going to call a narc, has uncovered their ruse, they’re back on the horns of the dilemma. Do they cut funding to their hospitals, with the obvious negative consequences? Or do they allow their ranking to plummet?

These rules have an odd selection effect on the sort of person who “wins” the game: who ends up, say, as the president of a prestigious university. It’s best to be sincerely idealistic, to believe that your institution is valuable for its college students. But it’s also best to be uninterested in having more students go to your college. How does one achieve this mindset?

The elite you will always have with you

In a guest essay in today’s New York Times, Michael S. Roth, the president of Wesleyan University, argues that more poor students should have access to a quality education.

Education transforms lives; we just need to make it more widely available.

Amen! But the way he talks about it is a little weird.

The best universities would be even better if they invested more in finding talented students in places they have historically overlooked — if they went beyond the usual metrics of meritocracy that elite families know how to use to their advantage.

…

But with quality instruction and even limited exposure to intensive learning, more heterogeneous groups of students would develop the appetite and aptitude for research and creative practice that selective colleges and universities seek.

…

The kids … learn that given a chance to work at a high level, they can become members of the educational elite.

I get a strong sense that in Roth’s vision, getting into a good college is still just as difficult and selective. The change he wants to see is a more “heterogeneous”1 cohort managing to get in, thanks to improvements in the pipeline for disadvantaged students.

Roth believes that a good college education helps people succeed: “A good college education opens pathways for transformative achievement.” So shouldn’t we try to get more people a good college education? Nah.

We will always have elites — some deserving, some not — and we will always have anti-elitists — some civic-minded, some cynical. Constitutional democracy doesn’t work if people are stuck in the station they’re born into, and education can still be an effective lubricant, and a powerful corrective to entrenched inequality.

I’m sure if you asked him if he wanted more people to get a good college education, he’d say yes. But even given a platform like he had today, Roth doesn’t talk about any kind of plan that would do so—only ones to ameliorate inequality, which sounds like the same thing (“everyone should have an opportunity to continue education as a young adult,” he says) but very much is not. He’s learned not to see the inefficiency, just the scarcity it produces.

Even when it’s kind of staring him in the face. He talks a good deal about how proud he is of Wesleyan’s participation in the National Education Equity Lab program, wherein students in high-poverty high schools get a chance to take an actual Wesleyan class, for credit. He’s taught one himself.

(He thinks it must be leading to more students going to college. Having been burned once or twice, I’m less optimistic. He touts an 80% pass rate for the course itself, which is depressingly close to the College Summit statistic that indicated a null result. I haven’t looked into it in detail.2)

But what the program does do, more definitively, is show that Wesleyan’s cost-per-credit could be 89% lower.3 If they ran their whole organization like the Equity Lab, they could serve almost ten times as many students. But then they wouldn’t be elite.

Fighting inequality by cutting costs

As Roth notes, students from disadvantaged backgrounds benefit much more from an elite degree than rich kids do. An old study found that your life outcomes don’t particularly improve from going to a selective college…unless your family is poor, in which case they improve dramatically. Estimates vary a lot for how much of this is due to the education itself, rather than the prestige of the degree, but even the most pessimistic attribute 20%.

So if Wesleyan admitted ten times as many students, the ones who would benefit from their decreased selectivity would be the disadvantaged ones. That’s how to fight inequality. Colleges have tried for over a century to admit more poor students, and have been consistently thwarted by rich parents spending more and more to restore their edge. But rich parents can’t force their children to make the most of their opportunity once they’re in, so that’s the battlefield you want for your class war. If you’re into that sort of thing.

I’m not proposing a solution in this article, just trying to clarify what the actual problem is. We’re in a proper coordination trap, where nobody can simply do something better and not get punished for it. But I do think this is fixable. Europe spent 150 years thinking of pineapples as the ultimate symbol of elite status. People in the mere upper-middle-class would rent a pineapple to come across as richer than they were when hosting a party. Today, you can get one at Walmart for $2.28, and you don’t even have to give it back uneaten the next day. We didn’t get there by holding Pineapple Lotteries so that people from all economic backgrounds had a chance to own a pineapple. We didn’t get there by handing out little pineapple cubes to promising teenagers in order to motivate them. We got there by making pineapples much, much cheaper to grow. That’s victory. Anybody who can shop at a Walmart is now a member of the elite.

Somebody must have told him not to use the word “diverse” in this political climate.

Okay, I did look a little. I think it’s probably doing a little harm, if anything, if it works like it did in the pilot program, where 476 students were chosen from 25 schools (assuming 1000 eligible students per school, that’s the top 1%), and then of the three quarters who actually ended up attending, 20% dropped out, usually “counseled to withdraw,” and another 11% didn’t pass. Even at Title 1 schools, the top 1% of students usually go to college anyway, but if half of them are kicked out of a college program, they might be discouraged.

The normal cost of a Wesleyan credit is $8,700. The Equity Lab says “over 900” students are in the top 20% of all scholars taking Equity Lab courses, so that’s about 5,000 students total. Its annual budget is five million dollars, so that’d make it $1,000 per credit.

Oh I have so many comments.

Q1: Many schools (I have more experience with big public state universities but also one elite private university) choose to give raises to the football coach and president and/or to make improvements to the football or basketball teams' spaces like stadiums, locker rooms, dorms for athletes, money to lure top ranking high school athletes. Sometimes it is to put luxuries in the dorms, gym, etc. to lure students to come because it looks nice to live on campus, since online learning is taking away from these money makers on campus.

Q2: This made me laugh. At the community college I teach at, students typically transfer to Arizona State University (overwhelming majority), Northern Arizona University, Grand Canyon University (private Christian nearby), or University of Arizona. At ASU there are 13 different psychology majors to choose from. They all have slightly different requirements for the math class, communication class, or science class needed to transfer and not have to retake or take extra classes. There is no sense they are trying to pare these down to one psych major but are perfectly happy to make more. I have plenty of other examples of duplicate programs within the same university. Some universities work on a financial model where every college within the university is competing with all the others for students' tuition dollars so they start doing sneaky, weird stuff.

I have been in department and faculty meetings where strategies to increase the US News and World Report ranking for the program/department was specifically discussed regularly, like every month.

Just as we saw in K-12 after the passage of No Child Left Behind where schools started teaching to the test and dropped everything else (the initial tests were only on reading and math so even now, decades later, some schools still don't teach social studies or science with any regularity because the reading and math scores are the only ones that determine school funding, etc.) we have seen the same pattern in universities with the US News and World Report rankings. They focus just on those metrics and ditch things there's plenty of data to show actually helps students succeed so it becomes this circle. But within my adult career I've also heard schools choosing to opt out of US News and World Report rankings as a backlash so there has been some movement in the time this has been on my radar.

Overall, I've never seen a university (big state school) choose smaller class sizes and lower teacher student ratio, it has always been pushing us to increase that and it has always been faculty pushing back that stops any of it (and we often lose). Even at my community college where our class caps are 24 (so lovely!) they are pushing for 30 or 35. So far the data shows they wouldn't actually save much money or even save any classroom space by doing this so we can push it off for now.

One of the things that we are dealing with is that with the 2008 recession people put off having kids and then some never did have them so there are simply fewer 18 year olds to start college these days and that number just isn't going to go back up any time soon based on population data in the US and yet the colleges and universities are all trying to figure out how to magically get back to the numbers of 5-10 years ago. For a community college with lots of returning/nontraditional students I would think Biden's proposal of free community colleges would maybe make a difference but that hasn't happened yet. Otherwise the things I see the administration of colleges and universities focus on really make no sense, but they often have never actually taught college classes, so they really don't know about the thing they have the power to make decisions on.

I think we need the same fix as with the health care system. Education and health care should be free. Period. Of course I don't know how to do that, but.... maybe you could figure it out. Please?